(pressing HOME will start a new search)

- ASC Proceedings of the 27th Annual Conference

- Brigham Young University-Provo, Utah

- April 18-20, 1991 pp 93-102

|

(pressing HOME will start a new search)

|

|

WORKER

SATISFACTION AND COMMUNICATION PATTERN ON CONSTRUCTION JOB-SITES

|

Philip

Udo-In yand Temple

University Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Statistical models showing the relationship between worker satisfaction and interpersonal communication pattern on construction job-sites are presented. Communication variables pertaining to construction job-sites were measured. Data was collected through self-administered questionnaires from craftsmen, including journeymen and apprentices. Subjects were located in the state of Missouri. Communication pattern was indicated by eight variables: method of job assignment, reaction to performance, feedback, accuracy, directionality, overload, distortion of information, and openness. Communication pattern variables were found to be significantly related to construction workers' satisfaction. Accuracy of information received and openness of superiors to workers were two important communication pattern factors in this relationship |

INTRODUCTION

This

study investigated existing modes of interpersonal communication on construction

job-sites and evaluated workers' perceptions and reactions to the different

communication patterns adopted by their foremen and superintendents.

Communication is used mainly to create a working understanding among interacting

individuals or groups. Instructions, rules, regulations, company policy, etc.,

have to be communicated properly to the workers in order for the organization to

function effectively. According to O'Reilly and Pondy [9], objectives of

communication include: to provide information, to obtain information, to make

decisions, to persuade someone, to instruct, to control, to coordinate, and to

express feelings (emotions). In order to achieve these objectives, Kerzner [6]

pointed out that "communication must convey both information and

motivation". Basically, this paper presents the statistical relationship

between construction worker satisfaction and interpersonal communication

variables using multiple regression techniques. Worker satisfaction partially

indicated the worker's perception that communication objectives are being

achieved at the job-site.

COMMUNICATION

Imundo

[4] defined effective communication as "the transfer of information with

intended meaning in ways that permit those to whom the information is

transmitted to receive, interpret, and act upon it in the way intended"(Fig.

1). The above definition and other definitions of communication involve the

transfer of information rather than the physical phenomena of how communication

is achieved. Tenah [11] referred to information as "the behavior-initiating

stimuli between sender and receiver and in the form of signs that are coded

representations of data. Data does not affect behavior of people or machines;

however, data may become information if behavior becomes affected". McLeod

[7] stated that "information is processed data or meaningful data".

Interpersonal communication, therefore, involves transfer of information that

will affect the behavior of the receiver in the manner intended by the sender.

Successful communication relies upon the proper encoding and decoding of

transmitted information. On the other hand, communication is not achieved when

there is no response from the receiver or the behavior of the receiver does not

correspond to the intentions of the sender.

O'Reilly and Pondy [9] also defined communication process as the

"actual transmission of information from a sender to a receiver, and the

meaning inferred". Transmission of information may be distorted by

interferences or obstructed by barriers. Imundo [4] enumerated different types

of barriers that may affect interpersonal communication in an organization under

three categories, namely: general, upward and downward barriers.

|

|

|

Fiq.1

Communication Process [Imundo, 1980]. |

PREVIOUS RESEARCH

Two

objectives of this study were to determine what type of interpersonal

communication pattern (and barriers) is obtainable at construction job-sites,

and what type of relationship exists between communication variables and worker

satisfaction. Others (mentioned below) have indicated that satisfaction is

related to productivity, therefore, it is important to determine how

communication may

be directly or indirectly related to satisfaction. The Business Roundtable in

its Construction Industry Cost Effectiveness Project Report [13], defined

productivity as a ratio of the output in units of products to the input

resources. Resources may be men, machines, and/or materials. Therefore, reducing

the amount of resources needed (input) to produce a certain unit of output

increases productivity. This indicates that productivity may be increased if

human resources are applied efficiently through effective interpersonal

communication.

Borcherding

[1] found that job satisfaction would help increase productivity of the worker.

Worker satisfaction is an attitude which can be enhanced by different factors.

Possibly, the exercise of effective communication on construction projects, as a

means of efficient utilization of human resources, would ultimately contribute

to increased productivity in the construction industry. Borcherding also noted

that the construction foreman is evaluated by management in terms of job cost

and subjective judgment. Communication skills of foremen have not been

specifically emphasized, unlike technical skills and experience. But, without

good communication skills, a foreman or superintendent cannot favorably

influence the work attitudes of the workers in order to foster productivity [Imundo,

4]. The Business Roundtable [12] also concluded that effective interpersonal

communication with workers may change their attitudes at work. This study was

done to find out how positive changes of attitudes may lead to better worker

satisfaction. In its other report, the Roundtable [13] stated that satisfaction

and performance of the workers are main contributors to increased productivity.

Clampitt [2] surveyed employees from the manufacturing and service industry and

claimed that interpersonal communication dimensions were related to individual

and group productivity. These studies suggest that productivity of construction

workers may be enhanced directly by interpersonal communication or indirectly

through job satisfaction.

O'Reilly

and Roberts [10] developed communication indicators in organizational settings

and a research instrument to measure these indicators. After analyzing data from

different types of subjects, such as military personnel, bank employees,

hospital personnel, etc., O'Reilly and Roberts developed seventeen indicators

for measuring interpersonal communication. Four of the eight communication

variables used in this study were derived directly from O'Reilly and Roberts

communication indicators. The other four variables are modifications of some of

their indicators to make them more applicable to the construction job-sites.

Guevara

[3] conducted the first documented study on communication in the construction

industry. While Guevara's study was directed to office personnel, mostly

managers at the top and middle levels, this study was directed to job-site

workers. Using survey research, Guevara studied the communication pattern

between and among the management levels: top, middle and bottom management. This

work examined interpersonal communication at the foremen-craftsmen level of the

construction industry. At the construction job-site, the superintendent should

establish a communication link with the foremen, who in turn should keep their

craftsmen informed and instructed on what to do. From McLeod's ['7] analysis of

classical management functions and from construction practices, the following

eight characteristics would differentiate job-site communication from

management-level communication: 1) job-site communication are mostly oral and

face-to-face; 2) more people are actively involved in a particular

communication; 3) immediate action is required or instant feedback is necessary;

4) communication breakdowns tend to be more costly to rectify; 5) people

involved in job-site communication come from different educational and

experiential backgrounds; 6) job-site management spends most of its time

directing and controlling construction activities, while top and middle levels

management devotes most of its time to planning and organizing; 7) job-site

management is more concerned with communicating technical matters within the

group (intea-group), whereas the top management primarily communicates

conceptual or strategic matters between groups (inter-group); and 8) job-site

management depends on detailed internal information for its communication, while

the top and middle levels management needs both internal and environmental

information in summary form for its communication. Due to these significant

characteristics, job-site communication should be analyzed and developed

separately from communication at the top and middle levels of the construction

company.

METHODOLOGY

This

work basically examined the relationship between communication pattern on

construction job-sites and communication outcome (Satisfaction) for the workers.

Worker satisfaction (SATISFY) indicated the fulfillment of worker's needs and

expectations through the communication process and also the general job

satisfaction.

Communication

pattern was identified by the following eight factors: 1) Mode of work

assignment (ASSIGN), which refers to the most frequent form in which

instructions are transmitted from the foreman to the worker for the worker to

take action to complete a job; 2) REACTION of supervision to workers'

performance, which involves communication in terms of expression of praises and

reprimands or non-expressions when showing indifference to worker performance;

3) FEEDBACK from communication may be information that is received as a result

of previous information sent out, and which may be based on opinions of others;

4) ACCURACY of communication indicates the similarity between the message that

the sender encoded and transmitted, and the message the receiver ultimately

decoded. Measurement was in terms of respondent's estimate of how accurate

he/she perceives the transmitted information to be; 5) Directionality (DIRECT)

refers to the general indication of the amount of contact the respondent had

with his/her superior on one hand and with his/her co-workers on the other; 6)

Distortion of communication flow (DISTORT) occurs when the nature of the massage

is changed by adding or deleting bits of information transmitted, or when other

things such as noise interfere with transmission of information; 7) OVERLOAD, as

used in this study, indicated two situations, namely, when a worker receives

more information than he/she can effectively use, and when a worker receives

insufficient information to perform his/her work properly; 8) OPENNESS indicated

the willingness of the worker and the opportunity available to communicate

freely with his/her superiors.

Survey

research method was used in this study in which craftsmen responded to 53-item

questionnaires. Some of the items are presented in Appendix 1. The

self-administered questionnaires were distributed to craftsmen as discussed

below, who then responded and returned the questionnaires individually. This

method guaranteed the anonymity and confidentiality of each respondent, and also

eliminated an interruption of work which would have resulted if an interview

format was used. Some questionnaire items were adopted from instruments used in

previous research [O'Reilly and Pondy, 9; Guevara, 3; Clampitt, 2] that measured

similar variables used in this study. Other items were formulated on the basis

of theories, research and construction practice. The draft questionnaire was

then subjected to different stages of development, including expert reviews and

pretest analysis [Udo-Inyang, 14].

A

pilot study was conducted before the main study. Names of a few construction

companies in the State of Missouri were randomly selected from construction

industry directories. Letters requesting permission for their workers to

participate in the survey were sent to the selected companies. Companies that

responded favorably were then forwarded a set of questionnaires to distribute to

their workers. The self-administered questionnaire, with return address and

prepaid postage, was then completed and returned separately by each worker.

Questionnaires were also given to labor union members through their

representatives. Finally, questionnaires were distributed to workers on State of

Missouri projects, which were visited by the authors. On-site interviews were

informal and were not recorded nor included in the data analysis that follows.

RESULTS

AND ANALYSIS

The

complete analysis of the data collected involved a number of statistical

techniques including descriptive procedures for obtaining frequency

distributions, means, standard deviations, etc.; Pearson correlation

coefficients for one-on-one variable relationships; linear regression modelling

together with stepwise and R-square methods for establishing relation between

dependent and independent variables. Statistical Analysis System (SAS) package

on a mainframe computer was used for data analysis.

Demographic Characteristics of the Workers

Sample

size was determined by the sampling method discussed above, which basically mean

that sample size equal to the total number of craftsmen available from the

selected companies and labor unions. In the pilot study, 78 questionnaires were

sent out to three companies from which 47 responses were received for a

60-percent response rate. In the main study, 105 out of 335 questionnaires given

out were received for a 31-percent response. The following are the descriptive

statistics for each of the demographic variables measured in this study.

TRADE:

Nine specific types of construction trades or crafts were identified in the

survey. The major trades that were strongly represented were carpenters,

ironworkers, laborers, and pipe fitters/plumbers, each representing more than

10% of the total respondents. More than one-quarter of the respondents were

carpenters.

UNION:

Over 86% of the workers sampled in this study were members of a trade union.

CREW

SIZE: More

than 42% of the respondents were in a crew consisting of one to five people.

This was followed by those in a crew of six to 10 people (at 36%).

The remaining respondents had more than ten people in their crew. The

average crew size for all respondents was eight. (Table 1).

|

Table

1. Descriptive

statistics of demographic variables. |

|

|

CRAFT

EXPERIENCE: Respondents had a large range of experience (from six months to 40

years) in their trades. However, most (55%) had 10 or more years of experience

in their trade. Average experience was about 12 years. FOREMAN DURATION:

Respondents had worked with their foreman from a short time of one month

to a maximum of 15 years. However, more than one-half of the workers (53%) had

worked with their foreman for one year or less. The average duration that the

respondents worked with their foremen was 22 months.

CREW

DURATION: Majority of the respondents (61 %) had worked with the same crew for

one year or less, and 90% of them had worked with their crew for two years or

less. The average duration in a crew was 16 months, which suggests frequent

changes in the size and constituency of a construction crew, thus an effective

approach to interpersonal communication on the job-site is required.

AGE:

The age composition of the construction workers who participated in the study

ranges from 20 years to 61 years. About 40% of them were within the age of 21

and 30 years. The average age was approximately 36 years.

SEX:

Most of the workers (96%) that responded were male.

Regression Analysis

This

statistical procedure was used to establish a relationship between the

communication pattern and worker satisfaction. First order linear regression

model was obtained with worker satisfaction (SATISFY) as the dependent variable

and communication pattern indicators as the independent variables. The

independent variables were categorized into two types as:

Qualitative

Variable

The

only qualitative variable in this model was ASSIGN, with five categories:

Assignment sheets (SHEET); Block or task diagrams (DIAGRAM); Photographs or

models (PHOTO); Verbal instructions (VERBAL); and Examples (EXAMPLE). These

categories were measured separately by five items on the questionnaire (Q9-Q13).

Therefore, ASSIGN variable was given values from 9 to. 13 (see below), depending

on which job assignment was most frequently used. In case of a tie from worker's

response, the category with a lower number was assigned.

Quantitative

Variables

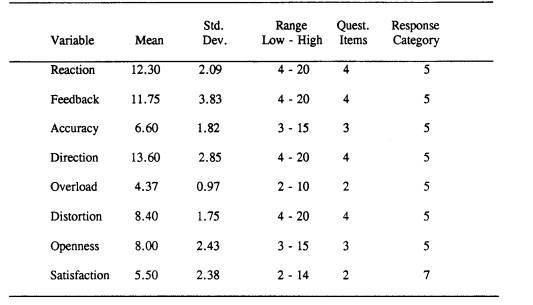

Seven

quantitative variables were included in this model: REACTION, FEEDBACK, DIRECT,

DISTORT, ACCURACY, OPENNESS, and OVERLOAD. These variables were each measured by

a number of items on the questionnaire and the value assigned to each variable

was a summation of responses to items under that variable (Table 2).

Pilot Study

The

first order general linear model obtained from SAS, using all of the above

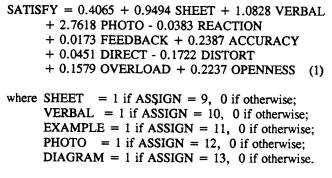

variables with the data collected in the first survey, was:

|

| Table

2. Descriptive

statistics of communication pattern variables and satisfaction. |

|

The

first parameter (bo = 0.4065) in equation (1) is the intercept of the

regression line when the mode of job assignment was either EXAMPLE (ASSIGN= 11)

or DIAGRAM (ASSIGN= 13), as these two dummy variables were not separately

represented in the equation. For other cases, we found that:

| when

ASSIGN = 9, SHEET = 1, then bo = 1.3959, when

ASSIGN = 10, VERBAL = 1, then bo = 1.4892, when

ASSIGN = 12, PHOTO = 1, then bo = 3.1682 |

Hence,

the above model is completely defined by four different parallel hyper-planes.

The variation from one plane to another was non-constant. That is, the change

from SHEET to VERBAL does not correspond to the change from VERBAL to PHOTO or

from SHEET to PHOTO.

The

overall F-test for regression was significant at the 0.0001 level with an

F-value of 7.759. This indicated that there was a statistically significant

relationship between the dependent and the independent variables. R-Square value

was reported at 0.6831, which may be considered statistically high. R-Square is

an estimate of the proportion of the variance of the dependent variable

accounted for by the independent variables [Kerlinger, 5].

The

partial T-tests, to test if bi=0, on each of the estimated parameters

showed that only three were somewhat significant at the 0.05 level of

significance. The coefficients for PHOTO, DISTORT and OPENNESS had T-test

p-values of 0.0538, 0.0017 and 0.0003, respectively. The other variable

coefficients were not significant at this level whereas the overall regression

was highly significant. This suggests the presence of multicollinearity among

independent variables in the model. Multicollinearity occurs when the

independent variables are correlated among themselves, also referred to as

inter-correlation [Neter, et al, 8]. Two variables found to be highly correlated

with other variables were REACTION and FEEDBACK, both of which had the highest

p-value of the T-test at 0.56 and 0.74, respectively. The major effect of multi-collinearity

is that the regression coefficients vary according to the number and type of

independent variables in the model.

The

first order model may not seem to be best fitted for the data at hand, although

the full F-test for regression was quite significant. Transforrhations on the

dependent variable (SATISFY) and on some of the independent variables (REACTION,

DIRECT and OPENNESS) were suggested from results of statistical procedures

conducted, which included analysis of Plots of Y and X's, Residual Plots, and

Univariate Analysis of Residuals [Udo-Inyang, 1989]. After performing analysis

of possible transformations, square-root transformation of the dependent

variable (RSATISFY) was then used to regress on all the original variables plus

three quadratic terms of REACTION, DIRECT, and OPENNESS. The full model had 13

independent variables, including three dummy variables, seven original variables

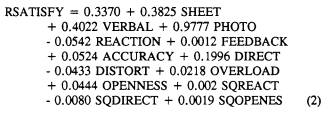

and three extra variables. The model thus obtained was:

|

Where

SQREACT, SQDIRECT, and SQOPENES are

the quadratic terms of REACTION, DIRECT, AND OPENNESS variables respectively.

The full regression Ftest was again highly significant. The R-Square value was

quite high at 0.7144, an increase of about four percent over the R-Square value

for the first order linear model (1). Also, four parameter estimates for the

variables PHOTO, DIRECT, DISTORT, and SQDIRECT were significant in the partial

T-tests.

Stepwise

Methods

Stepwise

regression methods were then applied to reduce the number of independent

variables to include only those that significantly contributed to the variation

of the dependent variable (RSATISFY). Three stepwise techniques (Forward

Selection, Backward Elimination, and Stepwise Regression) from SAS gave

different subsets in terms of number of independent variables selected. The

Forward Selection reduced model with nine independent variables was recommended

due to the high R-Square value (0.7121), which was virtually the same as that

for the fully expanded model with 13 variables. The nine independent variables

were: SHEET, VERBAL, PHOTO, ACCURACY, DIRECT, DISTORT, OVERLOAD, OPENNESS,

SQDIRECT.

R-Square/C

Method

The

R-Square/Cp procedure was also used to select the "best

subset" of the 13 independent variables, by optimization of the R-Square

and Cp values. R-Square value is maximized since it explains the

contribution of the independent variables in the subset to the variability of

the dependent variable. Whereas, Cp is minimized because it indicates

the predictive bias of the model to the data used. The maximum R-Square value of

0.7144 was obtained with all the variables in the model. However, more than 99%

of the maximum R-Square value was obtained with the nine-variable subset, when

R-Square was 0.7121. Considering R-Square only, the best subset contained the

nine variables deduced from the previous stepwise methods. For this same subset,

the Cp value (6.255) was low, and less than p = 9, the number of

variables in the model. Hence, the best nine-variable subset, as obtained in the

Stepwise Regression Methods, was recommended.

Thus,

from the Pilot Study, the final model adopted to estimate the relationship

between interpersonal communication pattern on the construction job-site and

worker satisfaction was:

|

From

statistical procedures discussed above, three repeatedly significant independent

variables in the model were ACCURACY, DISTORT, and OPENNESS. ACCURACY

and OPENNESS have positive coefficients, which infers that: 1) satisfaction

of the workers increases with high accuracy of information and instruction

received at work and/or high level of confidence of the workers; 2) worker

satisfaction also increases when the foreman communicated more freely and openly

with the worker and/or when the worker can communicate more freely and openly

with the foreman. DISTORT was negatively related to satisfaction in the model,

indicating that low interference in transmission of message or instruction

improves worker satisfaction, and better understanding of the foreman by the

worker and vice versa also increases worker satisfaction.

Main

Study

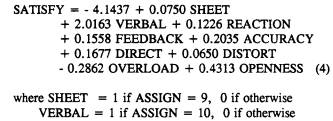

Again,

the full regression model was obtained with all the variables using data

collected from the main survey. Stepwise methods of model selection were then

used to produce the best variables combination for a linear fit of the data. The

first order general linear model obtained, containing seven basic independent

variables and two dummy variables, was:

|

The

other three "dummy" variables (EXAMPLE, PHOTO, and DIAGRAM) for the

ASSIGN qualitative variable (i.e., ASSIGN = 11, 12, or 13, respectively) did not

appear in the model due to the very low incidence of observations in these

categories. The first parameter (bo = -4.1437) in equation (4)

represents the intercept of regression line when ASSIGN was either EXAMPLE,

PHOTO, or DIAGRAM, in which case the two other dummy variables (SHEET and

VERBAL) would be zero.

Again,

the overall F-test for the regression was significant at the 0.0001 level with

an F-value of 10.508, indicating that the dependent variable (SATISFY) was

significantly related to the independent variables. The R-Square value was

reported at 0.4989, which may be considered high for a behavioral research. The

partial T-tests on each of the estimated parameters showed that only two were

significant at the 0.05 level of significance. These two were coefficients for

FEEDBACK and OPENNESS, with T-test p-values of 0.0072 and 0.0001, respectively.

All other variable coefficients were not significant at this level, which again

may indicate multicollinearity.

Stepwise Methods

Three

of the nine independent variables appeared in all the final subsets obtained

from the three stepwise procedures. Therefore, these three variables (ACCURACY,

FEEDBACK, and OPENNESS) would basically be considered the most important

variables in the

relationship

of SATISFY

variable with communication variables. The forward selection model (same as

Stepwise regression model) was recommended due to the high RSquare value,

which was about the same as that for the full model with nine variables. The

final model recommended from the stepwise techniques contained the following

variables: VERBAL, REACTION, FEEDBACK,

ACCURACY, OVERLOAD, and OPENNESS.

R-Square/C

Method

Most

subsets suggested in this procedure also contained the three variables

(ACCURACY, FEEDBACK, and OPENNESS) identified in the stepwise techniques as the

most important variables. The maximum R-Square value of 0.4989 was obtained with

all the variables in the model. About 99% of the maximum R-Square value was

obtained with the 6-variable subset, where R-Square was 0.4965. Therefore,

considering R-Square only, the best subset contained the following six

variables: VERBAL, REACTION, FEEDBACK, ACCURACY, OVERLOAD, and OPENNESS. For

this 6-variable subset, the CP value (4.447) was low and also less

than the number of variables in the model. The best 5-variable subset had a CP

value (4.505) which was closer but still lower than the number of variables in

the model. Considering only CP values, the best model would be the

5-variable subset. However, the R-Square value (at 0.4857) was lower than that

for the 6-variable subset (at 0.4965), therefore the best 6-variable subset was

recommended.

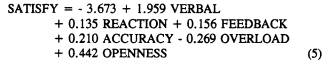

The

Stepwise techniques and the R-Square/Cp procedure suggested the 6-variable

model, with R-Square at about 0.5, and the p-value for the overall regression

model less than 0.0001 at F=16.108. This indicates that there was a strong

relationship between the interpersonal communication variables on the

construction job-site and worker satisfaction, as shown in the following

equation:

|

Equations

(3) and (5) show the relationship between communication factors and worker

satisfaction using the two sets of data obtained. Observed values of

communication variables may be inserted into the right-hand side of the

appropriate model (3) or (5) to obtain the predicted value for satisfaction. But

it is important to note that different sets of data give different coefficients

or parameters. Communication factors appearing in these models should all be

emphasized on the job-site. However, some of the communication variables in the

final models may be emphasized by job-site management more than the others,

depending on their relative contributions to the variation of worker

satisfaction. SATISFY had a range from 2 to 14 (Table 2), where 2 indicated that

the worker was very satisfied and 14 indicated that he/she was very unsatisfied.

The value of the right-hand side of equations (3) and (5) should be kept very

close to 2 in order to achieve high worker satisfaction. Similarly, lower values

for

communication

pattern variables signify better responses to these variables and vice versa.

Therefore, quantitative variables with higher coefficients (e.g. OPENNESS)

should be more emphasized than variables with lower coefficients (e.g.

REACTION). Also, variable with negative coefficient, such as information

OVERLOAD, should be reduced in order to increase worker satisfaction. As

measured in this survey, the worker should not receive more information at work

than he/she can effectively use, nor less information than required for

performing his/her work effectively.

CONCLUSIONS

Communication Pattern is Related to Worker Satisfaction

From

the above analysis and based on final models (3) & (5) obtained, it can be

concluded that worker satisfaction is related to interpersonal communication.

That is, the satisfaction of construction workers may be increased by

maintaining effective communication pattern at the job-site. A discussion of the

application and practical significance of the results follows.

Subjects and Situations

Most

of the craftsmen that participated in the survey were union members. Majority of

subjects belong to eight construction trades, which included carpenters, pipe

fitters/plumbers, laborers, ironworkers, sheet metal workers, operating

engineers, insulators, and teamsters. These craftsmen were involved in the

construction of a building or highway (roads and bridges) project. Hence, the

results presented in this study are applicable to the above subjects and

situations.

Barriers

The

supervisors on the job-site should eliminate communication barriers between the

workers and themselves. The following six barriers have been deduced from the

data obtained in this work: 1) showing unconcern or indifference; 2) noise or

distraction; 3) hidden agenda or messages; 4) lack of clarity; 5) poor listening

habits; and 6) not giving proper feedback [Imundo, 4].Workers who reported a

high frequency of occurrence of these barriers on the job-site, were less

satisfied with interpersonal communication. Therefore, the supervisors should

show interest in the activities of the workers and react frequently to them. At

the same time, supervisors should reduce unnecessary noise or distraction at the

job-site and provide the workers with the necessary agenda and messages. Daily

agenda and messages could be provided in a morning meeting or posted in a place

that is accessible to the workers each morning.

Important communication factors

Three

communication variables (OPENNESS, ACCURACY, FEEDBACK) were found to be

significantly related to the other variables used in this research. These

variables also contributed significantly in the relational model developed for

worker satisfaction. Hence, they may be considered as the most important

communication factors at the construction job-site.

OPENNESS

can be improved by creating ways that will make it easy for the worker to

communicate their feelings and ideas about their job condition with immediate

superiors. This could be done by having occasional group/individual meetings.

Supervisors should also make themselves easily available to the workers, without

intimidating them.

ACCURACY

may be ensured by providing the worker with specific instruction and information

that he/she needs at work in a timely manner, so that the worker would know

exactly what he/she is expected to do at work. Subsequently, there would be less

rework at the job-site due to incorrect instruction or information received.

Supervisors at construction job-sites should be very receptive towards workers'

FEEDBACK. This could be achieved by soliciting reactions or suggestions from

workers through personal questioning or providing collection boxes for

suggestions, and providing rewards for tangible ideas or suggestions.

Supervisors

should respond to each and every suggestion from the workers in other to

maintain their interest. Also, workers should be given ample opportunities to

participate in decision-making about work methods, safety, choice of the type of

work and choice of crew members, either collectively through their unions or

individually.

Satisfaction-Communication Models

Relational

models developed in this study were statistically significant at the 0.05 level,

even when the number of communication variables was reduced to only those that

significantly influence the variation of the dependent variable. Job-site

management should emphasize more on the communication indicators that appeared

in the final models (3) & (5), since these indicators were found to be

significantly related to satisfaction of the workers. These indicators were Mode

of job assignment, Accuracy of information, Reaction of supervisors to

performance, Feedback from workers, Openness of supervisors, Distortion and

Overload (Underload) of information that is received by the workers. However,

this does not mean that other communication indicators should not be emphasized

at the construction job-site. Other indicators may become significant if more

data is obtained and analyzed separately.

LIMITATIONS

This

study was limited geographically to workers in the state of Missouri.

Construction practices vary in different areas of the United States, and also

there are variations in the behavioral and environmental aspects. Thus, the

findings may not necessarily apply to all areas of the country.

Other

limitations include: 1) Data used for the analysis was

collected with a worker questionnaire, which was designed to be

self-administered and self-returned by the subjects. Interviews of the subjects

would be more appropriate for a behavioral research like this study; 2) Majority

of the respondents were union members. Therefore, it may be incorrect to

generalize the results to non-union construction workers; 3) Certain types of

crafts participated. About 19 categories of crafts exist in the construction

industry, but only eight crafts were actively represented in this study. As

such, it may be inappropriate to extend these findings to the other crafts that

did not participate in this research.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The

author wishes to thank the construction workers, the companies, and the

engineers of Missouri State Highway and Transportation Department for their

cooperation in the acquisition of data for this research. Also, financial

support from Exxon Research Grant for un-sponsored graduate research at

Department of Civil Engineering, University of Missouri-Columbia, is gratefully

acknowledged and appreciated.

REFERENCE

2.

Clampitt, P. G. Communication and Productivity. Thesis

presented to University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the

requirements for the degree ofDoctor of Philosophy. Lawrence, Kansas,

1983.

|

APPENDIX I. WORKER

QUESTIONNAIRE ITEMS

|

TRADE

UNION

CREW

SIZE

CRAFT

EXPERIENCE

FOREMAN

DURATION

CREW

DURATION

AGE

SEX

Response: (1) Very often (2)_ (3)_ (4)_(5) Never ASSIGNMENT

REACTION

FEEDBACK

DIRECTIONALITY

OVERLOAD

DISTORTION

OPENNESS Response: Very free and open (2)_(3)_(4)_(5)

Not free and often

SATISFACTION Response: (1)Very Satisfied (2)_(3)_(4)_(5)_(6)

(7)Veiy Unsatisfied

|