(pressing HOME will start a new search)

- ASC Proceedings of the 27th Annual Conference

- Brigham Young University-Provo, Utah

- April 18-20, 1991 pp 87-92

|

(pressing HOME will start a new search)

|

|

QUALITY IMPROVEMENT PROGRAMS FOR CONSTRUCTION

|

Jeff Lew Purdue University West

Lafayette, Indiana |

| This

paper explains and examines an ongoing technique commonly called

"Quality Improvement" (QI) that is currently being used in

industry. A review of the literature available on this subject was made

to obtain a summary of the development of QI to its present state.

Interviews were conducted with several companies to determine the

current state of Q1. An outline of the theory of a "Quality

Improvement Program" is presented next. Following then is an

overview of the principles, practices, and behavior which characterizes

a QIP, and a step-by-step charting of how the program could be applied

to the construction industry. |

INTRODUCTION

TO QUALITY IMPROVEMENT

A method to improve quality in the construction industry is now available in the form of a technique entitled either "Quality Improvement Program" (QIP), "Total Quality Management" (TQM), or a similarly-named program. The program's basic philosophy is based upon a company mission statement complete with objectives, mechanics, and an organization for the Quality Improvement Program. It is a voluntary program that stresses a quality process that is dynamic, and is able to respond to the needs of a world that is changing around us. All of these programs have evolved from an initial concept known as 'quality circles," but in their present forms are more refined and applicable to smaller businesses such as construction companies.

The

construction industry must be tuned to provide products and services that

satisfy the valid requirements and expectations of its customers. Construction

is a competitive business that is hurt by absenteeism, low morale and high

turnover. Quality Improvement is a method that can be used by contractors to

improve their competitive edge.

ORGANIZATION OF QUALITY IMPROVEMENT

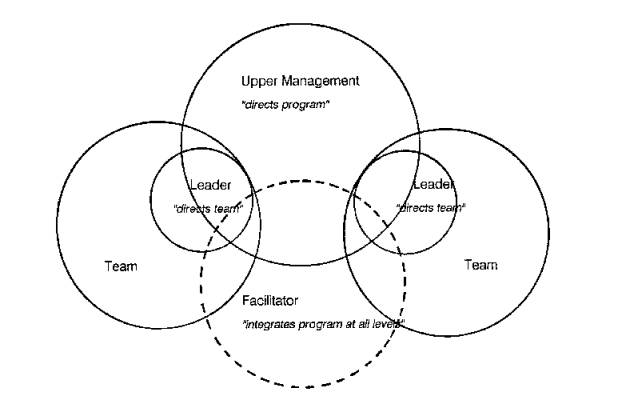

A

typical QIP/TQM organization is shown in Fig. 1, and consists of teams, team

leaders, facilitators, and management participation. The actual organization of

a program must be tailored to fit the needs of a particular company. However,

the organization and guidelines of ten different companies were examined and

found to be virtually identical to the program outlined in this paper. The

following paragraphs provide a brief description of the terms describing the

organization of QIP/TQM.

|

| Figure

1

Organization Model of a Quality Improvement Program |

Quality Improvement Tam

The

basic foundation for the entire quality program is the team. The team is a small

group of employees consisting of 3 to 13 people with the usual numbers being 7

to 9. Small groups are used to allow members to informally, comfortably and

effectively communicate their knowledge and ideas with all other members.

The

team members come from the same craft area or task oriented composite crew. This

is a prerequisite so that the members can discuss work related problems that

they have in common. The objects of the discussion are mutual improvement, and

the motivation to encourage self-development. Membership in the team is on a

strictly voluntary basis. Maintaining voluntary participation is important so

that the activities of the program will not interrupt the established work

schedule or procedures of the company, Normally, a team meets for an hour or so

each week at some mutually convenient time.

The

motivation to belong to the group is provided by the personal satisfaction

obtained from recognition given by management for achievements. Members become

selfmotivated when learning that management really cares. Employee recognition

was reported to be a major benefit of Quality Improvement Programs.

In

summary, the groups first sessions are devoted to learning the problem-solving

process, and the Quality Improvement Program, and refining communication skis.

The members are then encouraged and are free to mutually identify problem areas

and proposed solutions. The agreed upon solutions are recommended to management

for implementation.

Team Leaders

The

leaders of a team may be foremen or other supervisors appointed by management or

they can be elected by the group members. There are distinct advantages for

using supervisors as group leaders. First, the risk of creating authority

conflict is avoided. Second, the leadership of the team leader can be used

during the early training of group members. Third, when the team

leader

supports the team activities, the activities of the team will support the

leader. The team leader provides the liaison role between the team members and

the facilitator.

The

training of a team leader must focus upon the knowledge and skills which are

needed to conduct small group discussions and assist members to develop creative

thinking procedures. The five accepted qualifications for an effective group

leader are:

|

Facilitators

Key

to the success of the Quality Improvement Program is the backing of management,

which is the primary task of the facilitator. The facilitator must ensure that

the group efforts are recognized by upper management. For that reason, the

facilitator needs to be a person from middle management such as a project or

contract manager.

Facilitators

must understand the philosophy and dynamics of the program. They must be

experienced and trained in motivation theory, problem solving, group dynamics

and communication skills. A facilitator should be responsible for the start-up

of a new QIP/TQM program, and must direct the activities of several teams to a

common goal. When a common solution is reached by team members, the facilitator

assists the team leaders (or representatives) and supports the presentation of

the solution by the team to upper management. See Fig. 2 for a representation of

the facilitator's role.

Note:

Double boxes are problem-solving process steps

Single boxes are monitoring process steps |

| Figure

2: Step-by-Step

Process for a Quality Improvement Program |

Management Participation

The

highest level group for the program is provided by management participation,

with the key being the involvement of the Chief Executive Officer. The major

functions of the committee are to set up policies and procedures of the team

activities, and to direct the implementation of a team program. Team management

should determine what areas are off limits to team activities. These areas

usually include wages and salaries company benefits, interpersonal conflicts,

and anything directly concerning union contracts.

Since

commitment and recognition from top management are essential to the success of a

Quality Improvement Program, communication between top management and the team

is critical to team activities. In many cases the committee regularly publicizes

to employees, both members and non-members of the Quality Improvement Program,

the activities, progress, and success of individual teams. The objectives are to

provide the recognition from management, and to encourage more employee

participation.

PROGRAM STEPS

The

Quality Improvement Program process is shown in the flow chart contained in Fig.

2. The first four steps are part of the problem solving process. The last three

steps make up the monitoring phase. The paragraphs that follow explain the steps

in the process.

Improvement Required

The

objective of this step is to identify a subject or the problem area and the

reason for working on it. The key activities include defining & valid

customer requirements, brainstorming, establishing a subject selection matrix,

producing graphs and flow charts. When finished the team will be able to

graphically, or with a flow chart, visualize the need for the improvement.

Selection

of a Problem.

The

team selects the most significant problem from the list in Step 1. A target is

then set for the needed improvement. The key activity is to collect data from

all aspects of the problem, to write a clear problem statement, and to utilize

the data to establish the target.

Problem

Analysis.

This

step identifies and verifies the root causes of the problem area. The team

performs cause and effect analysis on the problem and verifies the selected root

causes with the collected data. Recommended Solution/Implementation. Once the

solution is pinpointed, the team presents the problem and solution directly to

management. The presentation will include graphs and flow charts to show the

solution that will correct the root causes of the problem.

Feedback

and Verification.

This

step is art of a monitoring process the team uses to verify that the root causes

of the problem have been adequately reduced, and the target goal for improvement

has been satisfied. This step uses a key element of comparing the problem

simultaneously before and after implementation, using the same indicator.

Systemizing.

This

step involves seeing that the solution has become part of routine work

activities and that the workers have been properly trained in the correct

techniques. The key element is to ensure that the root cause does not re-occur.

Re-Evaluation.

After

solving a problem the group reviews the process used and examines the lessons

learned in the process. The key activity for this step is to evaluate the team

effectiveness and then plan future activities for solving remaining problems.

DISCUSSION OF PROGRAM RESULTS

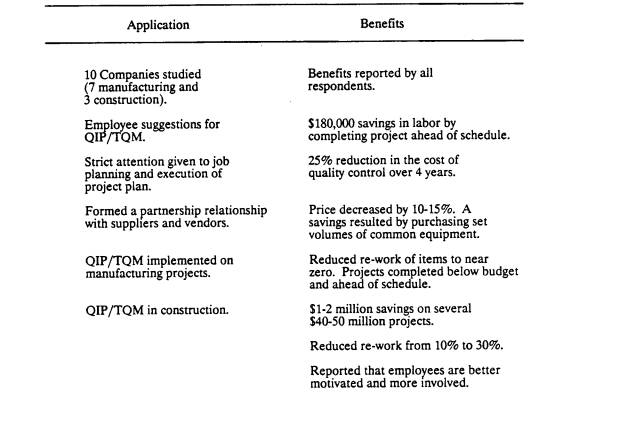

The

users of QIP/TQM reported benefits that are summarized in Table 1. While all

respondents reported benefits from the program, not all of the benefits could be

quantified in monetary terms, and showed minimal results at best. For this

reason, and after a number of years, the program was dropped by two companies.

Their reasons are summarized as follows:

|

QI TACTICS FOR CONSTRUCTION FIRMS

Historic

experience indicates that quality improvements can usually be made in most

operations. But the question that arises is: are these improvements short-lived,

or can they become permanent? This is a real concern for construction

operations. The following are some tactics for QIP/TQM that would help

construction firms, and which vary somewhat from the typical program outlined in

this paper.

|

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The

five points listed under Team Leaders (page four) are the basic qualities of a

good supervisor and manager. Those people within a company who exhibit these

qualities are usually promoted quickly, and tend to continue to be successful.

They then practice their own form of QIP/TQM that is informal and customized to

their own management style. The point here is that once people learn to

communicate, listen, and manage well, a company may not need a special program

to make improvements. These improvements would happen naturally. However, to be

properly managed from a QIP/TQM aspect, a company may need to employ a program

to ensure that its people are trained to the best of their abilities. Training

is essential to start a successful program and have it grow.

| Table

1. Summary

of QIP/TQM applications and benefits. |

|

Good

management techniques require looking at people, in addition to applying sound

management principles to a construction project. QIP/TQM could provide the

construction industry a methodology to involve workers, supervisors and

management in a team approach to solving problems. QIP/TQM allows employees to

become part of the solution, rather than part of the problem. This program is an

interesting and dynamic method to improve productivity, quality, and management

of construction work.

QIP/TQM

can be adapted for use in the construction industry. Construction firms thinking

of such a program should consider the following recommendations:

|

REFERENCES

|