- ASC Proceedings of the 42nd Annual Conference

- Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado

- April 20 - 22, 2006

|

Distance Education: A Learning Experience

|

Dennis C. Bausman, PhD, AIC, CPC, Lu Na, MS Construction Science and Management Clemson University |

|

Enrollment in college-level, credit-granting, distance education courses has increased almost four-fold in the 6 years between the first and latest United States Department of Education (USDE) study. While the use of distance education increases, concerns about the quality of education for this mode of delivery persist. This study examines the development of an asynchronous distance education offering for an undergraduate course in construction materials and methods. The foundation for the online course is a PowerPoint (PPT) lecture series developed for publication with the text. Breeze software was used to add audio to the PPT lecture series and short video clips were incorporated to support selected themes. Testing was accomplished online using randomly selected questions from a large test bank within Blackboard, the course management system. Learning outcomes from the online course were compared to a similar class using traditional in-class instruction. Based on quantitative outcome assessments, the online students scored equal to, or better than, the in-class students receiving traditional in-class instruction. Qualitative measurement support a similar conclusion: the vast majority of the online students thought they learned as much or more in this online course than they learned in a comparable course taught using traditional in-class instruction.

Key Words: distance education, internet, online education, construction education |

Introduction

Distance education is an educational delivery method that can be traced back to the start of commercial correspondence courses in the 1830’s. The U.S. Department of Education defines distance education as an “education or training course delivered to remote sites via audio, video, or computer technologies, including both synchronous and asynchronous instruction” (USDE, 2003). In essence it is “instruction delivered over a distance to one or more individuals located in one or more venues” (Phipps, Wellman, and Merisotis, 1998).

The first generation of distance education delivery methods originated with print and evolved to include radio and television. Second generation delivery methods included VCR and by the mid 80’s the third generation incorporated personal computers and videoconferencing. The continuing evolution of distance learning delivery methods has been greatly impacted by the Internet which provides ever increasing delivery options and student access (USDE, 1999).

A recent study conducted by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) for the U.S. Department of Education (USDE, 2003) investigated distance education in the US. It was the third step of a longitudinal research project begun by the USDE in 1995 (USDE, 1997) and followed up with another study in the 1997-1998 school year (USDE, 1999). The latest study was conducted by NCES in the spring of 2002 for the school year 2000-2001. The survey included 2-year and 4-year degree-granting institutions in the 50 states and the District of Columbia. The population for the three studies is very similar, but varies slightly because of the way NCES now categorizes postsecondary institutions. The self-administered survey for the latest study was mailed to 1,600 postsecondary institutions and had a 94% response rate.

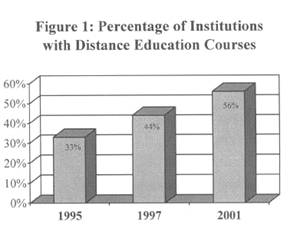

Figure 1 depicts the percentage of higher education institutions offering distance education courses at the time of each study (USDE, 1997, 1999, & 2003). Institutional offerings of distance education courses have grown from 33% to over 56% by the 2001 academic year.

Much of the growth can be attributed to the use of asynchronous computer-based technology for delivery. An USDE study of distance education programs during the 1999-2000 school year found that 60% of the undergraduate distance learning students were taking courses via the Internet (USDE, 2002). In addition, 19% of the institutions responding to the 2002 study indicated that they had degree or certificate programs delivered totally through distance education programs.

Of those institutions offering distance education courses during the 2000-2001 academic year increasing student access was a very important institutional goal of two-thirds of the respondents. Thirty-six percent (36%) of the institutions pursued distance learning to make educational opportunities more affordable and sixty-five percent (65%) saw it as a delivery option to access new audiences and increase student enrollment.

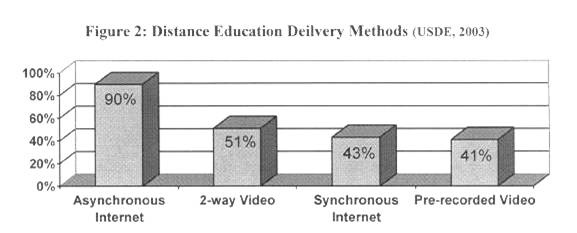

The latest USDE study found that the Internet and video technologies were the most common methods of delivery. Of those institutions offering distance education courses, the percentage using each delivery method is shown in Figure 2.

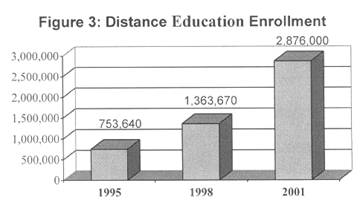

Enrollment in college-level, credit-granting, distance education courses has increased almost four-fold to 2,876,000 in the 6 years between the first and latest USDE study as shown in Figure 3: Distance Education Enrollment. The growth in distance education courses has been fueled by the emergence of new technologies, changing student demographics, and the need to reduce the cost of education (Sherron & Boettcher, 1997).

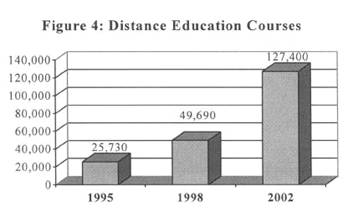

Accompanying the increase in enrollment, the number of distance education courses at 2- and 4-year institutions has grown nearly five-fold to 127,400 in the 6-year period (see Figure 4). Institutions are looking for delivery methods that reduce cost, and increase enrollment by reaching out to students that are opting for educational delivery methods that better meet their needs (Howell et al., 2003). Despite the high growth in course offerings and student enrollment there remains a large untapped market. During the 1999-2000 school year, the percentage of students participating in distance education at public 4-year institutions was only 6.9% and 9% in public 2-year (USDE, 2002) institutions.

Distance Education Outcomes

Student Learning

In spite of, or perhaps because of, the expanding use of distance education apprehension persists regarding its effectiveness as an educational delivery method. Russell’s often cited 1999 report titled The No Significant Difference Phenomenon attempts to address this concern. His study reviewed 355 research reports on distance education from 1928 to 1998. His study found that the learning outcomes of distance education students and traditional on-campus students were similar. In the forward to the study, Richard Clarke summarized Russell’s conclusions noting that “no matter who or what is being taught, more than one medium will produce adequate learning results … and we must choose the less expensive media or waste limited educational resources.” The findings of Russell’s study were similar to those of an earlier study conducted by Hanson and his colleagues (1997) in their review of the literature and research on distance education.

"The good news is that these no significant difference studies provide substantial evidence that technology does not denigrate instruction. This fact opens doors to employing technologies to increase efficiencies, circumvent obstacles, bridge distances, and the like. It also allows us to employ cheaper and simpler technologies with assurance that outcomes will be comparable with the more sophisticated and expensive ones as well as conventional teaching/learning methods." (Russell, 1999, Introduction)

Student Satisfaction

Allen and his colleagues (Allen et al., 2002) performed a meta-analysis of studies investigating student satisfaction with distance education. To be included in the analysis the study had to compare a distance education course with a similar course using traditional face-to-face methods of instruction. “The meta-analysis indicates a slight student preference for a traditional educational format over a distance education format and little difference in satisfaction levels. A comparison of distance education methods that include direct interactive links with those that do not include interactive links demonstrates no difference in satisfaction levels" (p83).

Allen’s (2002) results were similar to a USDE study that asked students to compare traditional in-class instruction with distance learning. The study found that 70% of the undergraduate students were more or equally satisfied with distance learning while only 30% were less satisfied (USDE, 2002).

Distance Education Obstacles

In spite of the strong growth of enrollment in distance education, and studies indicating comparable student outcomes, faculty and their institutions remain hesitant. While faculty support the increased student access and the flexibility that accompanies distance education they remain skeptical on several fronts. They are apprehensive because of the lack of student-teacher interaction and the reliability of the technology. Faculty members are also concerned about property rights and believe distance learning requires more work without fair compensation (NEA, 2001).

The American Federation of Teachers (AFT) and the National Education Association (NEA) commissioned The Institute for Higher Education Policy to conduct a review to assert the effectiveness of distance education. This study (Phipps and Merisotis, 1999) focused on research that had been conducted since 1990. Similar to the previously cited studies, they found that "with few exceptions, the bulk of these writings suggest that the learning outcomes of students using technology at a distance are similar to the learning outcomes of students who participate in conventional classroom instruction. The attitudes and satisfaction of students using distance learning also are characterized as generally positive" (p 1).

However, the study submits that "the overall quality of the original research is questionable and thereby renders many of the findings inconclusive" (3). In their opinion “technology cannot replace the human factor. [It] can leverage faculty time, but it cannot replace most human contact without significant quality losses. And many results seem to indicate that technology is not nearly as important as other factors, such as learning tasks, learner characteristics, student motivation, and the instructor" (Phipps and Merisotis, 1999:8).

The latest USDE study (2003) investigated the issue from an institutional perspective where resistance remains high. The factors identified in this study as preventing the start or expansion of distance education included: a) inability to obtain state authorization (86%), b) lack of support from institution administrators (65%), c) lack of fit with institution mission (60%), d) lack of resources (58%), e) inter-institutional issues (57%), and f) lack of perceived need (55%). However, a close review of this listing supports Bates’ (2000) position that perhaps “the biggest challenge [in distance education] is the lack of vision and the failure to use technology strategically’’ (7).

The Distance Education Course

Delivery Method

The concerns raised by the AFT, NEA, faculty, and institutional administrators primarily focus on student learning outcomes: the quality of the education that a student receives with distance learning compared to the traditional in-class delivery method. Frankly, this author was also concerned about the quality of the student learning experience with online instruction, especially when using an asynchronous method of delivery.

There are essentially two approaches for the delivery of distance education courses – either synchronous or asynchronous delivery. Synchronous is 'real time’ delivery permitting simultaneous participation and interaction of the students and instructor. However, with asynchronous delivery there is no simultaneous interaction between the students and/or the instructor. Unlike synchronous delivery, there is no scheduled class time and instructional materials are prepared in advance and the student is afforded access at a time convenient to him/her.

A course can be designed as 100% synchronous, 100% asynchronous, or a combination of the two delivery methods. For instance, a course could be delivered with lectures pre-taped and posted online for students to view at their leisure (asynchronous) and incorporate a chat room for class discussion (synchronous).

The distance education course examined in this study incorporated only asynchronous elements – there was no ‘real time’ participation or interaction between the instructor and the students. The only substantive ‘direct’ communication was via e-mail. The primary reasons that an asynchronous approach was adopted were:

Flexibility: for both the student and the instructor. Asynchronous delivery allowed the students to view lecture materials at a time convenient to them and freed up the instructor’s time.

Technology Considerations: An asynchronous approach often has less delivery complications and can require less band width. The course was designed to be offered to multiple remote sites, some of which most likely have lower transmission capacity.

Cost: Even though development time and cost can be higher for an asynchronous approach, once the course is developed, delivery cost can be lower because: a) instructor time is reduced, and b) class size can be increased without adversely affecting the quality of the learning experience.

Core Elements of the On-Line Course

The course used for the study was a sophomore course titled CSM 205 – Materials and Methods. The primary focus of the course is commercial construction, and its objective is to provide students with a basic understanding of building materials and construction techniques and methods. At the institution where this study was conducted, this class is a required course for both Construction Science and Architecture undergraduate students.

The subject matter for this course – Construction Materials and Methods - is well suited for the incorporation of graphics. As a result, graphics were often integrated into the lectures. Digital photos, diagrams, graphs, and video clips were used to help illustrate and/or illuminate a concept or construction process. The foundation for the course lectures was a Power Point lecture series developed in 2003 and published accompanying the current edition of the text for the course in 2004. This original PPT lecture series incorporated over 1200 digital graphics.

The primary systems and software used to develop and offer the course included Power Point as the baseline for the lectures. With the PPT material as a base, audio was added using a software program titled Breeze Presentation. Then, to further enhance student learning and understanding, short video clips were incorporated. Generally the video clips were limited to two per chapter and five minutes in length. The video clips were typically produced in-house, but a few were captured from sources on the web. To produce the in-house videos a digital camcorder was used to collect video from actual construction sites. Often the narration was provided by project supervision – a technique that was very effective because of their knowledge and passion for the work items being recorded. Windows movie maker was the software used to edit and produce the video clips.

All of the PPT lecture notes were converted to flash files and made available on demand. They provided the students a format to encourage, and facilitate, note taking while they were viewing the lectures. In addition, to accommodate the hearing impaired, the script was added to the PPT notes and made available to the viewer during the Breeze lecture.

Breeze permits a number of lecture presentation variations, but the format selected automatically flowed through the presentation without anything but an initial prompting from the student. However, a student could pause and re-play any portion of the lecture, using very simple commands that were explained in the Course Introductory lecture previously reviewed. In addition, each slide had a subject title to permit the student to view selected slides. This was particularly helpful to the students when studying for an exam or reviewing a particular subject that they did not fully grasp. Lecture modules were kept to a maximum of 50 minutes. Chapters running longer than that were segmented into multiple Breeze lectures.

The core elements of the course included a stand alone Breeze lecture designed to introduce the students to the course, and review the use of the online resources. The introductory lecture reviewed the course syllabus and the use and navigation of Blackboard. It provided an overview of the lecture format, the lecture notes, and the online testing planned for the course.

The Course Management System used for the course was Blackboard (BB). It proved to be user friendly system from both a student and instructor perspective. All the course materials were posted on, and accessed through BB. In addition, all student assessment was online and facilitated using Blackboard’s assessment tools.

The last primary component of the course was student assessment. All testing was performed online. Quiz and exam questions were randomly selected from a test bank that contained approximately 1,000 multiple choice and true/false questions covering the material presented in the text and the Breeze lectures.

To ensure that the student stayed on track with the reading assignments and viewing the Breeze lectures, a quiz or exam was given each week. Three times during the semester, the students were required to take an exam that covered the chapters reviewed since the last exam. Additionally, at the end of the semester each student was required to complete a comprehensive final exam.

A majority of the students taking this online class were ‘on-campus’. To ensure that each student completed their own work, students were required to take each quiz and exam during the same block of time at a designated proctored site. Remote students, if more than one at a site, were also required to take quizzes and exams at a proctored site.

Methodology

Comparative Courses

To effectively investigate and compare the quality of distance learning with traditional in-class instruction, the online offering was launched in tandem with a traditional in-class course. During the spring semester of 2005 two sections of CSM 205 - Materials and Methods were offered. One section incorporated traditional in-class instruction while the second section was offered using an online, asynchronous approach.

Study Samples

Enrollment in each class, or section, was by student choice. The online class had an enrollment of 34 students and the traditional in-class section had 30 students. To minimize the number of variables both sections had the: a) same instructor, b) the same lecture material and underlying Power Point lecture series, and c) the quizzes and exams were randomly drawn from the same test bank for both sections.

The other main variable was the quality of the students in each section. A comparison of the student populations of the online versus the traditional in-class yielded the following:

The ‘traditional’ class had a slightly better GPA. Students in the traditional class averaged 3.16 vs. 3.04 for the online students. However, statistically, there was no significant difference between the two samples regarding overall GPA.

The year of study for both classes was almost identical – second semester Sophomores.

The Online class had slightly more relevant work experience. Online students averaged 1.5 summers of work experience versus in-class with 1.3. However, again there was no statistically significant difference between the two samples.

The only significant difference between the two classes was the traditional in-class section had ten more architecture students than the online section. However, this difference is addressed in the analysis section of this report and did not have a material effect upon the results of this study.

In summary, the students in the online class had a similar educational ‘foundation’ and overall performance record compared to the students in the class using a traditional delivery method.

Data Collection and Analysis

Data for this study was collected during spring semester 2005 and analyzed during the summer of 2005. The statistical analysis of the data included the calculation of descriptive statistics, means testing, and the testing of paired samples. All statistical testing of the data was performed to a level of significance of 0.05. A copy of the detailed test results is available from the author upon request.

Findings

Quantitative Assessment of Student Learning

During the semester students in both sections were given 10 quizzes, 3 exams, and one comprehensive final exam. A comparison of the student scores from both sections yielded the following results:

Quizzes: Student scores for the quizzes were compared and statistically analyzed. On 3 out of the 10 quizzes the online students outperformed the in-class students. The online students consistently scored equal to, or higher than the in-class students.

Exams: The mean scores on the 3 exams were almost identical for the two sections. There was no statistically significant difference in outcomes on the exams.

Final Exam: On the final exam the traditional class average was 78% (a high C) while the online students averaged 83% (a low B). When the outcomes were statistically compared there was a significant difference. The online students outperformed students in the traditional in-class section.

CSM Students: The traditional class had significantly less construction science and management (CSM) students and more architectural students than the on-line section. To evaluate if this disparity had an effect on the quantitative assessments the results for just CSM students for each section were statistically compared. Except for one quiz, there was no statistically significant difference in outcomes between the two sections.

In summary, on quantitative outcome assessments the online students scored equal to, or better than, the in-class students receiving traditional in-class instruction on all three measures – quizzes, exams, and the comprehensive final exam.

Qualitative Assessment of Student Learning

At the end of the semester, the online students were asked to complete a course evaluation survey. The questionnaire was structured to obtain some basic student information such as year of study, GPA, and their experience with online classes. However, the majority of the questions were developed to get the student’s assessment concerning the usefulness and quality of the course components as well as their opinion regarding the educational value of the online course. Students were advised that their responses were anonymous and confidential. Thirty-four (34), or 100%, of the students responded to the survey. The significant findings are as follows:

Prior Experience with Distance Education:

Nineteen (19), or 56%, of the students indicated that they had previously taken an online course. The majority of the students had prior experience with an online offering.

Learning Aids:

Several of the questions asked about the usefulness of some of the course learning elements. The findings were:

Twenty-seven students, or 79%, thought the introductory/orientation lecture was helpful in understanding the course requirements and resources. Six students were undecided, and only one student thought the lecture was not helpful.

97% of the students thought the lecture notes were a helpful learning aid. Only one student was undecided.

Twenty-five, or 74%, of the students thought the use of video clips increased there understanding of the subject matter. Only one student felt they did not aid the learning process.

Text Quality:

Several of the questions asked about the text and the quality of the lecture presentation as well as the effectiveness of each as a learning aid. The findings were as follows:

Seven (20%) of the students did not read or study the material in the text. Eleven typically spent 1-2 hours per chapter, thirteen indicated 3-5 hours, and three spent more than 6 hours reading and studying each chapter of text.

Overall, twenty-six (76%) of the students felt the text was well written and a useful source of information.

Lecture Quality:

All of the students viewed the lectures with 19 viewing each chapter’s lecture at least once, 12 students viewing each twice, and 3 students reviewing each lecture 3 or more times.

Thirty-two, or 94%, of the students thought the quality of the lecture audio and graphics was good or very good.

Thirty-one, or 91%, felt the lectures significantly increased their understanding of construction materials and methods.

Course Overview:

33 of 34 students, or 97%, thought the overall quality of the lectures and other course materials was excellent or good.

91% of the students indicated that they would recommend the course to a friend.

The majority of the students thought the online course required the same, or more, time than a comparable class with traditional in-class delivery.

82%, or 28 of 34 students, thought the course information was presented in an interesting way that held their attention. Six students were undecided and only one thought the course was uninteresting.

91% of the students indicated that the course met, or exceeded their expectations. (10 students felt the course exceeded their expectations, 21 indicated it met theirs, and only 3 said it did not meet their expectations.)

Online vs. Traditional Delivery

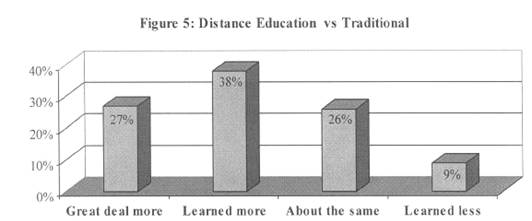

Lastly, the students were asked: “To compare what they learned in this online course with a comparable course delivered with traditional in-class instruction”. It should be noted that most of these students had taken a companion materials and methods course the previous fall semester. Their evaluation of the online course was as follows (and as depicted in Figure 5):

27% indicated they learned a ‘great deal more’, 38% indicated they ‘learned more’, and 26% said they learned ‘about the same’. Only 3 students, or 9%, felt they learned less.

In summary, 91% of the students thought they learned as much or more in this online course than they learned in a comparable course taught using traditional in-class instruction.

Conclusions

In summary, the results of this comparative study confirm that:

Based upon the quantitative assessments of student learning (quizzes and exams), the performance of the distance learning students was equal to or better than, the performance of the students receiving traditional in-class instruction, and

The distance learning students were satisfied with the course and perceived it to be well constructed and an effective learning method.

The quality of the learning outcome was not sacrificed with the distance learning delivery method, and the student’s perceived experience was viewed satisfactory and beneficial. Based on the data from this comparative study, an on-line, asynchronous approach can be an effective delivery method to achieve student learning.

It also proved to be a very demanding, yet rewarding experience for the instructor and researcher. It forced me to experiment with new technology and experience first hand the challenges and rewards inherent with new delivery methods. The process was a true learning experience – for both the instructor and the students.

Bibliography

Allen, M., Bourhis, J., Burrell, N., and Mabry, E. (2002), “Comparing student satisfaction with distance learning education to traditional classrooms in higher education: a meta-analysis”, The American Journal of Distance Education, 16(2), 83-97

Bates, T. (2000) Distance education in dual mode higher education institutions: Challenges and changes.

Online: http://bates.estudies.ubc.ca/papers/challengesandchanges.htm

Hanson, D., Maushak, N., Schlosser, C., Anderson, M., Sorensen, C., and Simonson, M. (1997), Distance Education: Review of the Literature, 2nd Ed., Washington DC and Ames, IA: Association for Educational Communications and Technology and Research Institute for Studies in Education.

Howell, Scott L., Williams, Peter B., and Lindsay, N., (2003) “Thirty-two trends affecting distance education: An informed foundation for strategic planning”, Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, v VI, n III, Fall

NEA – Higher Education (2001), “A survey of traditional and distance learning higher education members”, National Education Association, June 2000

Phipps, R., Wellman, J., and Merisotis, J. (1998), Assuring Quality in Distance Learning: A Preliminary Review. A report prepared for the Council of Higher Education Accreditation, Washington, DC

Phipps, R., and Merisotis, J. (1999), What’s the Difference? A Review of Contemporary Research on the Effectiveness of Distance Learning in Higher Education, Washington, DC: The Institute for Higher Education Policy

Russell, T.L., (1999), The No Significant Difference Phenomenon, Chapel Hill, NC: Office of Instructional Telecommunications, North Carolina State University

Sherron G., and Boettcher, J., (1997), Distance Learning: The Shift to Interactivity, CAUSE Professional Paper series #17, Boulder, CO: CAUSE

U.S. Department of Education (USDE), National Center for Education Statistics (1997), Distance Education in Higher Education Institutions, NCES 98-062, by Laurie Lewis, Debbie Alexander, and Elizabeth Farris, Washington, DC

U.S. Department of Education (USDE), National Center for Education Statistics (1999), Distance Education at Postsecondary Education Institutions: 1997-1998, NCES 2000-013, by Laurie Lewis, Kyle Snow, Elizabeth Farris, Douglas Levin, Washington, DC

U.S. Department of Education (USDE), National Center for Education Statistics (2002), A Profile of Participation in Distance Education, NCES 2002-154, by Anna C. Sikora, Washington, DC

U.S. Department of Education (USDE), National Center for Education Statistics (2003), Distance Education at Degree-Granting Postsecondary Institutions: 2000-2001, NCES 2003-017, by Tiffany Waits and Laurie Lewis, Washington, DC