|

(pressing HOME will start a new search)

|

|

WorkStyle Profile for Construction Students: A Time to Stretch

|

Ken Walsh Del

E. Webb School of Construction Arizona

State University Tempe,

Arizona |

Ray Newitt The

McFletcher Corporation Scottsdale,

Arizona |

|

This study is a follow-up to Badger and Wanner (1991) to explore the degree of alignment between the Constructors' PREFERRED approach to work and the ACTUAL requirements of their positions. In order to assess the impact of their implemented educational recommendations, the WorkStyle Patterns" Inventory (WSP') was administered in 1994 to another group of construction students. A comparison between the two student groups reveals that individual preferences are difficult to influence, WorkStyle Alignment has not improved and the potential for Personal and Organizational Stress (based on work approach) for the 1994 study group is at higher levels than in the general workforce. Recommendations for educators, industry, and students are provided with an emphasis on a partnership requiring all to stretch beyond what is traditionally comfortable. Keywords: Productivity, Organizational Effectiveness, WorkStyle Stress, Construction Management, Professional Development, Alignment |

Introduction

In

"The Educators Role, Aligning The Peg And The Hole," Badger and Wanner

(1991) identified the primary role of the construction educator was to

"meet the needs of the construction industry by providing quality graduates

(who) bring technical knowledge to improve industry performance." They went

on to identify a significant lack of alignment between PREFERRED WorkStyles and

construction industry requirements as a key issue requiring the attention of

both the educator and the construction industry. Badger and Wanner recommended

the following three-pronged approach for improving the misalignment identified

in the study:

1.

Attract potential constructors with appropriate WorkStyle preferences for the

Construction Profession (educator).

2.

Integrate managerial and interactive skills in construction schools' curriculum

to influence student preferences (more "management" in Construction

Management, educator).

3.

Be sensitive to workforce professional development

and

career pathing (industry).

Badger

and Warmer's (1991) recommendations regarding educational approaches focused on

the work preferences of students attracted to the program and the methods for

educating these students. In an attempt to implement these recommendations, the

Del E. Webb School of Construction (DEWSC) at Arizona State University modified

their recruiting and educational approaches. A follow-up study to the Badger and

Wander (1991) study was conducted in October, 1994, to assess the impact of

implemented educator recommendations and to identify additional insights to

provide direction for the future. This paper compares the results of the

follow-up investigation with Badger and Warmer's (1991) initial work and

provides further recommendations for improvement. Comparisons will be based upon

the undergraduate student responses of both studies who respectively represent

38 (1991) and 49 (1994) students.

Alignment Instrument

The

concept of alignment addressed by Badger and Wanner originated from The

McFletcher Corporation's WorkStyle Patterns (WSP) Inventory. The WSP alignment

assessment process is based on a comparison between actual work requirements and

the way people prefer to approach work activities. This assessment determines

WorkStyles; how an individual prefers to work (the want) and how an individual

views his or her current position's ACTUAL work (the is).

This

assessment also reveals the discrepancy between the individual's preferred

approach to work and the position's required approach to work. Descriptive

WorkStyle Profiles provide comparative data about the workforce and their work

activities. This knowledge enables employees and employers to work together for

closer alignment which creates greater organizational productivity and enhanced

individual satisfaction.

The

premise of the WSP°" Alignment process is that each person prefers and

each position requires different degrees of TASK, PROJECT, and ORGANIZATION

Orientation activities. The degree to which a person prefers to exercise each

Orientation determines his or her PREFERRED WorkStyle. The degree to which a

position requires that each Orientation be carried out determines its ACTUAL

WorkStyle.

There

are four WSP Orientations which represent how an individual prefers to think

about work or how the work requires whoever is in the position to think about

the work. These Orientations are:

TASK

Identification

with the Product or Service, through performing specific work activities.

PROJECT

Identification

with Projects and their People through coordinating and linking activities.

ORGANIZATION

Identification

with Goals and Results through initiating organizational activities.

ADAPTING

Identification

with all three types of activities through a combined Orientation that balances

all three Orientations in a responsive and supportive manner.

The

inventory consists of 18 statements (9 PREFERENCE, 9 ACTUAL) with 4 responses

per statement. Individuals rank the four responses per statement from 4 (meaning

most) to 1 (meaning least). Completion of the WSP"" Inventory

generates numeric scores for each of the Orientations. These scores are used

to determine a WorkStyle Profile. WorkStyle Profiles reflect the combination of

Orientation scores, a "pattern" of the work approach. The WorkStyle

Orientation represents the thinking mode to work, whereas the WorkStyle Profile

represents the way to carry out that thinking. The degree of misalignment

between the PREFERRED and ACTUAL Orientations and Profiles indicates potential

individual and organizational stress, or productivity and individual

satisfaction.

Changes in Educational Approach

Badger

and Wanner (1991) identified significant misalignment in their study group as

preferences to work independently conflicted with position requirements to

work interdependently with improved coordination. In response to these

findings and in an effort to improve the identified misalignment, DEWSC modified

its educational approach in two main areas: recruitment and group learning.

While the changes to be discussed below are occurring in many educational

arenas, the Badger and Wanner (1991) results provided an impetus to accelerate

adoption of the following modifications at DEWSC.

Recruitment

The

Del E. Webb School of Construction, in partnership with local industry, has

developed the Construction Recognition Banquet as an annual recruitment event.

The focus of the event is to expose high school students and education

professionals to the exciting opportunities in construction. This banquet

showcases construction and construction professionals to outstanding high

school students, educators, and guidance counselors. Interaction and informal

discussions between students, educators and professionals are key to the

success of this event. This is accomplished by seating at least one

representative of the local industry and one DEWSC faculty member or student at

each table. The Outstanding Woman Contractor and Outstanding Minority Contractor

awards are given at the event, and a keynote lecture is presented pertinent to

the construction industry.

Following

the observation of significant misalignment in the 1991 study, the emphasis of

the presentations at the Construction Recognition Banquet have changed. The

requirements that constructors be "team players," and be able to

coordinate and manage complex projects with complicated staff requirements have

been stressed in recent years. This theme is also reflected in revised

recruiting videos and brochures in the hope of attracting more students with

preferences in these critical areas.

Group Learning

In

addition to recruiting students with preferences to work interdependently, the

faculty at the School created increased opportunities for group learning, team

experience, and coordination in the curriculum. Group projects have become a

part of most courses within DEWSC. The objective of each project is to provide

educational contact with a particular subject area. However, taken

institutionally, the objective is to provide opportunities for students to

develop skills for working in teams and understanding group dynamics

throughout the educational process. Some faculty members argue that this goal is

as important as the contact with the individual subject areas.

The

operation of team assignments is different in each course. In some courses

students are allowed to choose their own groups, while in other courses

instructors determine group membership. Sometimes a group leader or spokesperson

must be selected. Usually the group product consists of a written document and

an oral presentation of results, though at times only a written report is

required. By providing a variety of group experiences in different courses, each

student experiences a number of group roles, a variety of group compositions,

and a multiplicity of "ground rules." Team assignments are intended to

serve as an experiential model for the operation of actual projects or project

management after graduation, albeit on a smaller scale. In this way, the

students should have an increased understanding for the character of the

construction industry, and be better prepared to join its ranks as more

productive members.

Evaluation/Discovery

In

order to evaluate the impact of the change; in educational approach, a

comparison between the student groups of the 1991 and 1994 studies is presented

in this section. The 1994 data consists primarily of students it their last year

of the program. Because moss students who were seniors in 1994 were recruited

prior to the change in recruiting approach, the data does not necessarily

reflect the impact of the change. However, it doe: provide insight into the

effect that more group learning opportunities had on individual preferences.

WorkStyle PREFERENCE Results

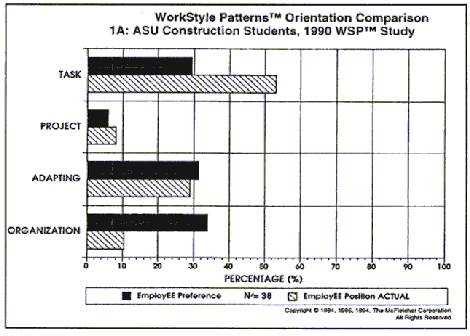

Figure

1 presents the WorkStyle Patterns' Orientation comparison between the 1991 and

1994 study groups.

|

|

|

Figure

1A. |

|

|

|

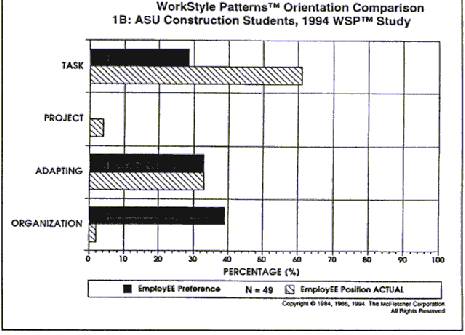

Figure

1B. |

The

WorkStyle PREFERENCE results (solid bars) in Figure 1 substantiate WorkStylc

Patterns" historical trends that skill development and training do not

change individual preferences; but rather provide opportunities for individuals

to effectively manage WorkStyle differences. A comparison o: Figures IA and 1B

reveals similar percent ages for the TASK and ADAPTING approaches from the 1991

and 1994 study groups. The two figures also reveal an increase in the ORGANIZA

TION approach and a reduction in the PROJEC7 approach. The initial objective for

instituting the educational changes described above was to reduce TASK

Orientation and increase the PROJECT and ORGANIZATION Orientations of the graduates.

However, based on these results, the increase in group learning activities

appears to have had a negligible influence on student preferences away from

the TASK Orientation. In other words, it is very difficult to change the way

people like to do their work.

As

stated before, the WorkStyle Patterns" Inventory requires respondents to

rank four responses to each of the nine statements dealing with preference (from

"4" meaning "most" to "1" meaning

"least"). A review of response rankings of the 1994 study group for

the WSP"" Inventory PREFERENCE statements provides insight that

supports the group's higher ORGANIZATION to influence goals and results and

lower PROJECT PREFERENCES to coordinate projects and people.

Most Preferred Student Responses

The

following responses are the study group's highest ranking responses for each of

the nine statements dealing with preference:

|

Know

how the project fits into the larger context. Work

with people who understand what the goals are. Work

with people who have stimulating and innovative ideas. Respond

to activities that require my specialized talents. Map

out forthcoming events and requirements. Work

in an environment where there is communication. View

new experiences as opportunities. Carry

out individual activities that show results. Set

priorities and target dates. |

The

majority of these responses reflect a WorkStyle PREFERENCE to understand the

whole and to be involved in a broader context.

Least Preferred Student Responses

The

following responses are the study group's lowest ranking responses for each of

the nine statements dealing with preference:

|

Be

in the middle of things. Participate

only when something is interesting. Work

with people who are willing to be a part of the group. Respond

to people's needs and feelings. Schedule

tasks for others. Work

in an environment where others do not expect a lot in a short time. Observe

and evaluate the reactions of others to new experiences. Coordinate

own activities with those of others. Find

people to help. |

For

the most part, these responses depict a low PREFERENCE for a work activities

that includes group involvement and coordination.

Based

on the trend from the comparison of Badger and Wanner (1991) with the 1994 data

(Figure 1), the impact of modification in the DEWSC educational process has been

negligible. However, there are certain benefits to the increased use of group

learning outside of the hoped-for modification of PREFERENCES. The use of these

tools introduces students to an interactive environment they will encounter upon

entering the workforce. Additionally, there is evidence that student retention

rates may be significantly increased over traditional approaches (National

Training Laboratories).

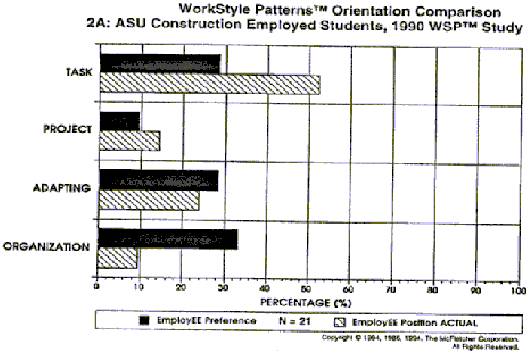

Position ACTUAL Results

Similar

to PREFERENCES, the ACTUAL Orientations are the nine statements (from

"4" meaning "most" to "1" meaning

"least") dealing with how individuals actually work. From an ACTUAL

WorkStyle perspective, it is important to look at the subgroup (Construction

Employed Students) of students who have or had employment in the construction

industry and were able to use their constriction industry position as their

frame of reference in responding to the WSPO Inventory statements about how they

perceived their ACTUAL work requirements. This subgroup comprised 55%of the

original study group and 57% of the current study group participants-a majority

in both .

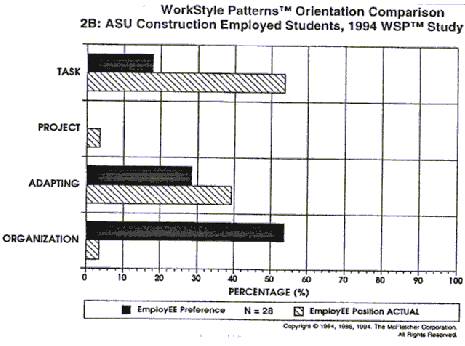

While

students' PREFERRED activities increased in ORGANIZATION Orientation to

influence goals and results from 1991 to 1994, a comparison of the WorkStyle ACTUAL

requirements depicted with striped bars in Figure 2 reflects reductions in both

the ORGANIZATION and PROJECT requirements. The TASK requirements reflected a

minimal increase (52%to 54%) while the ADAPTING approach posted the largest

increase, from 24%to 39%. The TASK and ADAPTING Orientations comprised 93%, or

26 out of 28 of the total 1994 respondents of the Construction Employed Students

Sub-Group. This is a little surprising when nine students held positions such as

Owner, President, Construction Manager, Project Manager, Assistant Project

Manager, Superintendent, and Foreman-positions which would be expected to

reflect PROJECT and ORGANIZATION Orientations.

As

was presented earlier in the discussion of PREFERENCE data from Figure 1, are

view of ACTUAL Response Rankings supporting the 1994 Construction Employed

Student Sub Group results presented in Figure 2 provides insight that supports

the groups higher TASK and lower PROJECT and ORGANIZATION ACTUALS.

Most

Required Work Activities for Construction Employed Students ACTUAL

The

following responses are the study group's highest ranking response for each of

the nine statements dealing with the positions' ACTUAL requirements:

|

Contribute

own skills and expertise. Focus

on individual accomplishments and contributions. Concentrate

on own immediate tasks and responsibilities. Decide

who should be apprised of new information affecting operations. Be

knowledgeable and communicative. Don't

like to receive conflicting instructions. Need

a productive environment and appropriate tools or processes. Advise

appropriate person of incorrect work of others. Carry

out tasks that contribute to organizational goals. |

These

activity responses largely reflect a WorkStyle ACTUAL that focuses on individual

skills, responsibilities, and contributions.

Least

Required Work Activities for Construction Employed Students ACTUAL:

The

following responses are the study group's lowest ranking response for each of

the nine statements dealing with the positions' ACTUAL requirements:

|

Challenge

or change the work being done. Improve

the image of the organization. Take

responsibility for what others are doing. Ignore

new information unless it is in one's own area of responsibility. Be

an influential force. Obtain

approval for decisions. Challenges

to deal with forces larger than self. Use

incorrect work of others to evaluate purpose of assignment. Interpret

organizational goals to others. |

These

activity responses reinforce the WorkStyle ACTUAL focus on individual

contribution presented above and not on the group or organization as a whole.

Though

this study does not evaluate the impact of the construction industry on the

WorkStyle ACTUAL responses, it does reveal the following potential concerns

when compared with the PREFERENCE data:

The

trend seen in the decrease in PROJECT PREFERENCE of the Total Study Groups (5%

to 0%) and the decrease in perceived PROJECT ACTUAL (14% to 4%) of the

Construction Employed Student subgroup is headed in a precarious direction.

Due to modern day re-engineering efforts, organizations often need more

coordination and communication and more people who prefer such activities to

compensate for Middle Management and Supervisory positions that, no longer

exist. Re-engineering efforts have been observed to have these effects in all

industries, which are not specific to the construction industry alone. It is

McFletcher's observation that when perceived PROJECT activities decrease, there

is an unwelcome increase in ADAPTING activities as employees respond to

surprises, lack of coordination and other unplanned events. In fact, according

to McFletcher's research, if the ADAPTING ACTUAL reaches and exceeds 40%, the

entire organization or industry enters a state of crisis management which is

difficult, if not impossible, to reverse.

|

|

|

Figure

2A. |

|

|

|

Figure

2B. |

Looking

at the Construction Employed Student SubGroup in Figure 2 the increase in

ORGANIZATION PREFERENCE (33% to 54%) combined with the reduction in perceived

ORGANIZATION work requirements (ACTUAL) (10% to 4%) further increases

discrepancy between student preferences and opportunities for influencing goals

andresultsfrom24%to50%. This growing misalignment will contribute to both

Personal and Organizational Stress.

Alignment and WorkStyle Stress

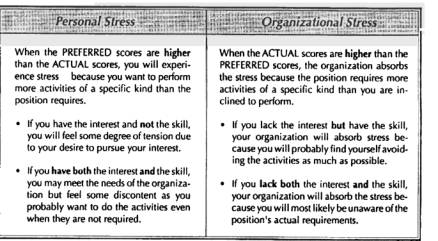

Alignment

simultaneously embraces the concepts of productivity and stress. A discrepancy

between one's PRE FERRED WorkStyle and one's ACTUAL WorkStyle car produce

various degrees of stress, which may be manifested in a variety of ways (Table

1). Typical personal response: to discrepancies include apathy and/or low

productivity, irritability and frequent complaints, and health disorders or

illness. A person with a significant WorkStyle discrepancy may even make changes

in the position in order to meet his or her own personal needs. This can cause

both Personal and Organizational Stress. Organizational Stress can be observed

through misunderstandings of work expectations, product quality and customer

service problems, missed deadlines, and higher turnover.

|

|

|

Table

1. |

In

addition to differentiating between Personal and Organizational Stress, it is

important to determine the level of stress from the degree of misalignment.

That is to say, the greater the discrepancy between the PREFERRED and ACTUAL

Profile scores in each Orientation, the more stress is manifested. The

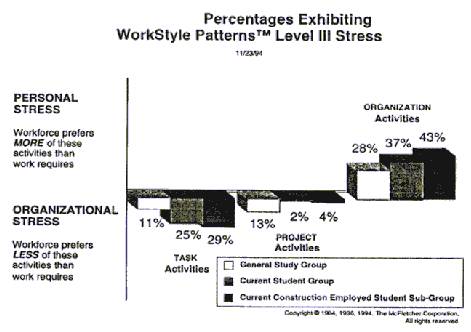

McFletcher Corporation identifies three Levels of Stress based upon the degree

of misalignment between the PREFERRED and ACTUAL Orientations. The most

significant condition is referred to as Level III Stress, and indicates a

conflicting difference likely to impact both the individual and the

organization. Figure 3

represents

Level III Stress percentages for the McFletcher General Study Group, the current

ASU Construction Student Group, and the current Construction Employed Student

Sub-Group. The General Study Group represents respondents from a variety of

industries and professions in the McFletcher Corporation's Data Base. A

comparison of the student groups with the General Study Group indicates that:

|

|

|

Figure

3. |

As

indicated from this study's sampling, the construction industry might be

experiencing much higher Organizational Stress (Level III) in the TASK

Orientation than the General Study Group. The discrepancy is even worse for the

Construction Employed Students Subgroup (students prefer much less task).

Employees

in the construction industry might be experiencing a much higher level of

Personal Stress in the ORGANIZATION Orientation than the General Study Group.

This picture worsens when you identify that 82% of this group are between the

ages of 23 and 32-meaning they could experience this level of stress for many

years to come.

Partnership with Industry

Even

though Badger and Wanner (1991) identified the need for educators to partner

with the construction industry to address the misalignment challenge, efforts focused

on educators adjusting the education process-recruitment and curriculum

content/processes. From the study results presented earlier, misalignment

actually increased. The recruiting process may eventually influence the

increased enrollment of students with preferences for working interdependently

in teams; however, given the nature of entry to the department, dramatic changes

in the type of student attracted to construction are unlikely. And even though

the curriculum adjustments provided increased opportunities for teaming and

coordination (skills development), preference results presented earlier showed

negative alignment results-attempting to change individual preference is not a

successful strategy.

If

changing preference is not a successful strategy, maybe influencing the design

of the positions graduates win occupy has merit (position actuals). What will

motivate industry to make such changes? It is natural to think that while

industry will not ignore the personal misalignment stress among employees, it

might be more motivated to deal with organizational (misalignment) stress-the

idea that required activities are not being performed. Also, from Table 2B,

the Adapting Actual (39%) is approaching 40%, a potentially dangerous level

according to McFletcher research-an indication of crisis management.

The

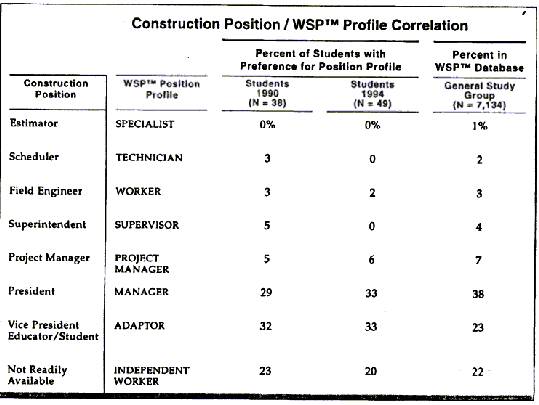

need for industry action on position design can be further demonstrated by

evaluating the WorkStyle PREFERENCE Profiles as correlated with construction

positions by Badger and Wanner(1991). Using these correlations and the PREFERRED

Profiles developed by each student who completed the instrument, the breakdown

shown in Table 2 was developed.

The

position designations mown are not to imply that a particular group of students

will end up in these roles. They represent the percentage of students who have

preferences for work which, were they in the indicated position, would align

closely to create a more productive match. Each student would end up in a

position which closely matches their preference in a perfect world. However,

more than likely many will end up in other kinds of positions. In any event, if

these percentages do not match up well with the percentages required in each

position, then misalignment and WorkStyle stress among the work force would be

expected.

From

Table 2, these scenarios can be projected as this group enters into the

construction world:

A

large number find their first jobs as estimators and schedulers. Because these

positions are TASK oriented, a large percentage of the group will experience

Level III ORGANIZATIONAL Stress as they learn some of the basics of the

industry. They will welcome any kind of participative effort their companies

sponsor such as team training, group planning sessions, project reviews with

customers, etc. Those who move into superintendent positions will be able to

utilize the associated skills acquired during their educational years, but will

require close coaching/mentoring to experience success in the position and to

minimize Level III ORGANIZATIONAL Stress in the PROJECT Orientation.

|

|

|

Table

2. |

As

members of the group move on to project manager positions, a large percentage

will be more closely aligned to their PREFERRED ways of working and should demonstrate

a higher level of productivity.

Because

a high percentage prefer an ADAPTING approach, those fortunate enough to move

into the limited number of vice presidential positions will be responsive

and flexible, but also vulnerable to burnout as they try to accomplish multiple

goals with short deadlines.

Those

who prefer the INDEPENDENT WORKER approach will appreciate TASK Oriented

work but not find the degree of autonomy they seek. Some of these may leave

their employer once they believe they have enough experience, capital and contacts

to operate independently as a company president.

Summary and Recommendations

Following

the work of Badger and Wanner (1991), a 1994 study was performed with anew group

of students to identify their WorkStyle PREFERENCES and ACTUALS to determine

the impact of the original study's implemented recommendations on the

WorkStyle Alignment of DEWSC's Construction Students. Despite exposure to change

in the educational approach, WorkStyle Preferences of the 1994 group show little

change from the Badger and Wanner (1991) group and the perception of ACTUAL work

requirements in the construction industry has changed in such a way that

misalignment increased-not decreased. According to McFletcher Data Base

research, this misalignment translates into Level III Personal and

Organization Stress at higher levels than the General Study Group (See Figure

3).

Based

upon the results of the 1994 Study and the research/ experience of the

McFletcher Corporation, educators, industry, and students have multiple

options to reduce and/or constructively manage the misalignment and associated

stress. In order to better serve the Construction Industry and their students,

educators should:

Continue

the interactive group learning approach to develop skills, create awareness, and

enhance the learning process-no preference with skills is better than no

preference without skills.

Continue

current efforts in the recruitment process, but consider administration of the

alignment instrument earlier in the educational process to provide a more timely

assessment of recruiting efforts and early of the alignment concept to students.

Early student awareness of this concept is critical in the planning/preparation

process.

Provide

opportunities for successful graduates to return as guest lecturers in

appropriate classes and student organizations to share experiences related to

growth opportunities (ORGANIZATION activities) beyond TASK oriented positions.

Consider

expanding the current alignment research in this area to include additional

universities and small and large construction firms to validate and enhance

current findings.

Initiate

partnership activities with industry and students through such avenues as the

Construction Industry Institute and the Alliance for Construction Excellence.

Through

the initiation of partnerships with industry, educators position themselves to

share research activities and request the participation of industry through:

Adjusting

the work content of positions that new graduates will enter to include

ORGANIZATION activity opportunities. Include such projects as evaluating TQM

process improvements and developing safety programs into entry level positions

to prepare employees for future responsibilities and reduce Personal Stress in

the ORGANIZATION Orientation.

Active

participation in the educational and recruitment process to obtain high quality

graduates. This would include attending banquets, being (providing) a guest

lecturer, and participating in partnership organizations.

Participation

in future alignment research activities by providing time, access to personnel,

and funding to ensure a competitive edge.

A

consistent commitment to professional development and career pathing for all

employees to reduce turnover and retain high quality professionals.

A

commitment to understanding the alignment concept and working with employees in

the formulation of plans (individual and company) to constructively deal with

misalignment to enhance profitability.

would

be easy to stop here and place the total burden of misalignment and its

resulting stress on educators and industry. However, it is important to identify

that students ire an important component in the alignment equation and seed to:

Be

realistic and patient about the amount of time required to work through TASK

Oriented positions to get to the ORGANIZATION Oriented positions.

Understand

the alignment concept and deal with misalignment constructively. Work with

employers in the creation of plans to reduce both Personal and Organizational

Stress.

Validate/clarify

individual perceptions of ACTUAL work requirements with Employer ACTUAL requirements-IS

versus SHOULD BE. Commit to and be accountable carrying out those requirements.

Be

prepared to stretch between a PREFERRED approach to work and the required

ACTUAL while developing a skill base to support preferences.

McFletcher

research indicates that as alignment improves and/or misalignment is

constructively managed, satisfaction and efficiency increase while turnover

decreases. All should realize that individual preferences are strengths that

individuals bring to organizations and will help maintain the vitality of the

industry. Industry should work jointly with employees to utilize these strengths

appropriately. The current misalignment gap will never disappear completely, but

it will narrow as educators, industry, and students commit to working

individually and collectively on the recommendations outlined above. All need to

stretch.

Acknowledgements

The

authors are grateful to the excellent staff of the McFletcher Corporation for

their assistance in the preparation and editing of this document and for use of

the data referenced herein. We also wish to thank Bill Badger and Chip Wanner

for their input and counsel in the preparation of this study.

References

Badger,

W. W., and Wanner, C., "WorkStyle Profile for the Constructors-The

Educators Role; Aligning the Peg and the Hole," Annual Conference

Proceedings, ASC, 1991, pp. 121-134.

The

McFletcher Corporation, WorkStyle Patterns""(WSPI) Inventory

(Copyright 1979, 1982, revised 1984, 1988, and 1993), 10617 N. Hayden Road,

Suite 103, Scottsdale, AZ 85260, (602) 991-9497.

The

McFletcher Corporation, WorkStyle Normative Data (Copyright 1984,1986, 1994),

10617 N. Hayden Rd., Suite 103, Scottsdale, AZ 85260, (602) 991-9497.

National

Training Laboratories, Workshop Materials, Bethel, Maine.