(pressing HOME will start a new search)

- ASC Proceedings of the 25th Annual Conference

- University of Nebraska-Lincoln- Lincoln, Nebraska

- April 1989 pp 87-94

|

(pressing HOME will start a new search)

|

|

CONSTRUCTION

SUBCONTRACTING AS AN EDUCATIONAL TOPIC

|

John Mouton and Hal Johnston California Polytechnic State University San

Luis Obispo, California |

| The

evolution of subcontracting has had a substantial impact on the

construction process. An increasing portion of building construction

projects are contracted to specialty, trade contractors. As a group,

subcontractors contribute significantly to the capital risk, resources,

managerial effort, and business expertise supporting the largest

industry in the country. Collegiate construction programs should address subcontracting issues to increase the awareness of students to the impact of and opportunities in subcontracting. The reference material used in

most courses is oriented to the general contracting sector without

explanation of key operational and managerial differences found in

subcontracting. A prime example is emphasis on project management

considerations (ie., scheduling) as compared to multi-project management

methodology. The paper addresses the

opportunity to include subcontract management topics in existing courses

in lieu of establishing a separate course. Key Words: Specialty

Contractors Subcontractors, Multi-Project Management, General

Contractor-Subcontractor Relations, Curriculum

Planning Course Development |

As

construction educators, there are four specific questions to be answered in

regard to Construction Subcontracting as an Educational Topic.

First:

Is subcontracting a significant factor in the building industry?

Second:

Do management techniques and decision processes in speciality subcontracting

differ from those applied in general contracting?

Third:

How do General Contractor - Subcontractor relations influence the success of bid

proposals, project time and quality, and the associated project risks?

Fourth:

Are these topics given adequate attention in the current curriculum and courses?

The

intent of this paper is to provide a summary statement to facilitate the

reader's answers to the first three questions and to suggest opportunities to

develop an appropriate curriculum response to the fourth.

EVOLUTION

OF SUBCONTRACTING

A

review of the evolution of speciality subcontracting sheds light on many current

issues. If there was an original impetus to subcontracting, it was the movement

from generalized to specialized construction craft trades. With the anticipated

improvement in worker skill, productivity, and product quality came the complex

question of effective and cost efficient utilization of these speciality skilled

craftsmen.

Given

the apparent and actual improbability that a General Contractor would sustain an

adequate amount of specific skilled craft work (eg., painting, masonry) on a

year-round basis, the more skilled workmen found better opportunities with

companies that specialized in their specific work area. The trend toward more

subcontracted work accelerated as the technical development of building

materials and methods escalated the requirement for craft skill and knowledge.

Quality control and labor management problems on construction projects became

less complicated for general contractors utilizing specialty trade

subcontractors in lieu fo furnishing all craft labor themselves.

A

cause and effect of this evolution has been a redistribution of the project

risk. Utilizing a subcontract bid and resulting contract, the General Contractor

fixes the cost of an in-place segment of work at the time of the project buy-out

with the specialty subcontractor responsible for cost overruns.

One

indication of the influence of subcontracting is to look at the cost breakdown

of typical building projects. While some Construction Management and General

Construction firms do subcontract 100% of the technical trade work, the

subcontracted amount seldom decreases below 50%. Depending on the type and

complexity of the project and the capability of the General Contractor, the

subcontracted portion of the total contract (including general conditions and

contractors fee) is typically 65% to 80%. The size and volume of these firms has

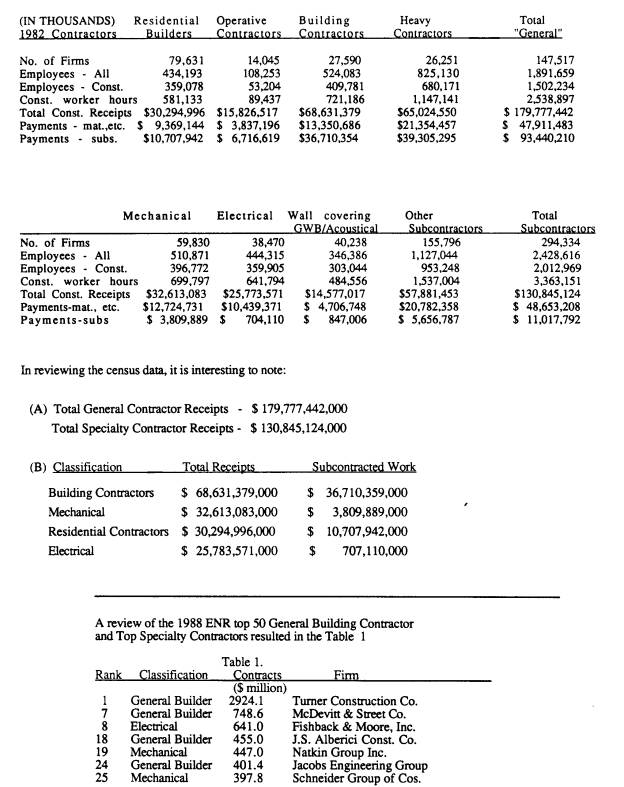

also increased. They now rank with the largest building contractors (Figure 1.)

and as a segment of the industry, they have larger volumes and numbers of

employee than many of the "General" catagories. (Table 1.)

| Table

1 & Figure 1 |

ENR's

listing of top specialty subcontractors, when compared to their listing of

top building contractors, indicates that at least the top three in each category

(Mechanical, Electrical, Structural Steel, Etc.) had an annual contract

volume that would have placed them in the top fifty list of the building

contractors. |

PROFILE

OF SPECIALTY CONTRACTORS:

As

a general rule, students view their future role in the construction industry as

that of General Contractor or Construction Manager. This perception is , of

course, fostered by the predominance of General Contracting firms involved in

on-campus employment recruiting, the slant of many of the text and course

reference materials, the support of particular industry associations, and the

prior experience of many faculty.

A

potential conclusion could be that many students do not recognize the

significant role of speciality contractors nor the the explicit differences in

managerial style and application required of those subcontractors. In many

instances, they are also unaware of the tremendous opportunities that exist for

graduate constructors in specialty construction areas.

The

management of resources and project coordination efforts for most specialty

subcontractors are significantly different than the comparable tasks in a

General Contractor's operation. Many specialty contractors will contract

directly with Owner on a single contract basis or as one of a number of multiple

prime contractors on a given project. These relationships result in different

methods of project coordination and interface. The specialty contractor must

respond to these differences engaging in a role that combines the managerial

characteristics of the typical General Contractor and the typical Subcontractor.

Manpower

utilization and distribution over a number of projects is a dynamic problem for

specialty subcontractor managers. Their potential for solutions differ greatly

from the resource management alternatives available to a General Contractor. A

well prepared Specialty Subcontractor's project manager will anticipate problems

and potential conflicts and supply appropriate managerial and technical

experience in a pro-active manner to assure the performance of others upon whom

he or she relies. As an example advanced analysis of the actual project

status/project progress provides the forward looking specialty contractor,

multi-project manager with a reliable source of information for company wide

resource planning, allocation and control.

The

Subcontractor's procurement and management of material and equipment involves

the collection and preparation of a number of submittals that must be processed

through the General Contractor and Architect/Engineer's organizations prior to

order. The contractual relationship may inhibit the Specialty Subcontractor's

leverage in this process. Attentive, well educated subcontractor project

managers will enhance their firm's managerial position by requesting, receiving,

and documenting submittal procedure process and approval time commitments at the

pre-construction conference. A missed opportunity can have detrimental results

impacting the Subcontractor's project schedule and profitability.

It

might be beneficial to consider some of the project coordination issues facing a

mechanical project manager. Often, their work includes second tier

subcontractors (eg., ductwork, controls); writing and managing of specific

performance contracts is essential. Crews are often cycle on then off the

project. As an example,

the plumber will complete the under-slab and site piping later returning for the

above slab rough-in and finally returning to install fixtures and trim out. Of

course, demands on other projects often necessitate that the individual phases

will be accomplished by different crews resulting in increased coordination

problems including completion of as-built drawings. Labor leveling is complex if

achievable.

Code

issues and inspection requirements are other areas of concern for the

subcontractor's project manager. The performance specification often establishes

acceptance as operational success which is not determined until the final days

of the project. Problems are frequent and response time limited. Prior planning

and appropriate resource allocation are essential to satisfactory project

completion.

Equipment

procurement involves a number of suppliers relying on a multitude of submittals.

Given that crews work mostly with small pieces and small tools, the handling and

setting of major equipment is complex in that it is short in duration with a .

significant resource demand.

The

Subcontractor's typical source of work is the General Contractors that assume

responsibility for complete construction of the project. At any point in time,

the subcontractor is providing specialty construction services to a number of

General Contractors with varying expertise in subcontract development,

subcontractor management and relations; project management, coordination, and

control; and project cash-flow reliability. Additionally, a regional

Subcontractor will repeatedly, and often on simultaneous projects, contract with

the same General Contractor. Decisions on individual projects are often

influenced by the objective of sustaining an on-going relationship. Both the

short-term (project) and long-term (future contracts) relationships with the

General Contractors are essential to the success of all specialty

subcontractors.

It

could be observed that the Specialty Subcontractor has less control of his/her

own destiny than does the General Contractor, but that need not be true. These

and a large number of other issues occurring on a number of simultaneous

projects with fluctuating schedules and various managerial approaches is a

complex arena in which the prepared Subcontract project manager achieve success

and the ill-prepared struggle to survive.

GENERAL

CONTRACTOR-SUBCONTRACTOR RELATIONS

Construction

Claims Monthly states "No issues are of broader concern to the construction

industry than the issues arising out the relationship between prime contractors

and their subcontractors." [1]

In

education, we include significant depth and breadth of coverage of the General

Contractor-Owner relationship, Architect-General Contractor relationship, labor

relations, and organizational behavior with less than complete address of the

significant issues in General Contractor-Subcontractor Relations. As General

Contractors, our alumni are dependent upon their subcontractors for the

successful completion of their projects. It is a certainty that the project

personnel have far more involvement with, and their success will be more

dependent upon, the Specialty Subcontractors that with the Owner, Architect, or

labor groups.

Negotiations

between the General Contractor and Subcontractor are ongoing throughout the

duration of the project. Issues include job staffing, sequence of work, quality

and quantity of work in place, interface with other work, schedules and progress

projections, progress payments, and change management. Successful negotiators

are knowledgeable and ever aware of the other sides' needs, desires,

requirements, and position. The General Contractor who understands the technical

and managerial problems of the Specialty Contractor is in a position to motivate

as well as respond to the true needs of the subcontractor resulting in an

increased probability of meeting the critical responsibility of delivering a

quality project on time.

Major

specialty contractor associations identify prompt payment, actually lack

thereof, as the principle problem faced by subcontractors. Bid shopping and

ineffective change management resulting in non-compensatable extra work are also

major concerns. The managerial opportunities and ethical issues involved in

these critical General Contractor-Subcontractor relationship factors should not

be ignored in the education and training of the future industry leaders.

"Unless

the subcontract states otherwise, the prime contractor has a duty to schedule

work so that subcontractors will no be delayed in the performance of their work

or forced to perform work out of

sequence" [2] Delay and disruption claims by subcontractors are increasing

and courts, experienced through contractor's delay claims against owners are

validating the specialty contractors claims.

Many

specialty contractors (eg. finishing trades ) continually find themselves in an

acceleration mode on a number of their projects. The cost (overtime) impact

and/or quality issues (larger crews with less skilled craftsman) of acceleration

can be damaging to both reputation and profitability. While it is not always

possible to bid the anticipated overtime or acceleration and be competitive, it

is possible for subcontractors to favor general contractors with better managed

projects when bidding. This consideration is recognized by specialty and general

contractors alike.

The

student or graduate who perceives the answer to technical and managerial

questions to be "we'll subcontract that", has not been adequately

prepared. Subcontracting work without understanding the technical aspects and

coordination implications places ones destiny in the hands of others. In

technical and managerial courses, the potential problems and anticipated

position(s) of the subcontractor can and should be included as a foundation for

the future success of the student(s).

SUBCONTRACTING

TOPICS IN EXISTING COURSES

Well

established collegiate construction programs often experience difficulty in

attempting to incorporate additional course work in the curriculum. Given

general education requirements, the limited number of elective courses, and the

breadth of construction topics considered essential, the consideration to add a

new course must answer the question: what can/will be eliminated?

The

authors of this paper anticipate that curriculum planners and construction

educators will find it more expedient and potentially more effective to expand

current course coverage to include subcontract issues in lieu of concentrating

that information into a single new course. It is recommended that a subcontract

topic outline be developed and compared to existing course content. The topics

can then be assigned on a programmatic basis expanding the student's preparation

to engage in the complexity of Subcontractor -General Contractor relations.

The

following suggestions are based on topical rather than course breakdown in an

attempt to facilitate curriculum planning and

development

given the individual construction programs course strategy.

Technical

Courses:

Given

that many of the technical areas of project execution are typically

subcontracted, courses that address those topics can easily and appropriately

include subcontract issues. Most construction curriculum separate the building

systems, including Plumbing, H.V.A.C., and Electrical, into a course series. The

courses are often classified as technical emphasizing design and operational

topics while ignoring the subcontractor's project coordination issues and

installation methods. The courses should include a focus on the materials,

methods, sequence, and technical interface phase.

These

systems and other (i.e. , curtainwall, roofing) subcontracted items have a

substantial impact on the initial and life-cycle cost of the project. Value

engineering applications and constructability studies that are technically based

and economically derived can be included; the students will develop a relevant

decision process that will serve their professional needs as a negotiating

conduit between the Owner's Architect/Engineer and the Specialty Subcontractor.

The

technical execution of the specialty work will always interface with other work

performed by both the General Contractor and other Subcontractors. The

discussion of required methods provides an ideal opportunity to address schedule

interface from a sequence, duration, and resource allocation standpoint.

Projects

developed in each course should be expanded beyond the typical technical

design-operation questions to include cost and resources estimates, schedules

with crew durations identifying potential pre-assembly work, and scope of work

(for contracts) statements.

Project

Management Courses

The

management of building construction projects includes the management of

subcontracted work by the General Contractor and the management of individual

areas of work by the Specialty Subcontractor. The managerial success of the

project is, to a large degree, dependent on the interface and abilities of a

multitude of managerial decisions executed by and influencing a number of

managers. Coordination of these effort are key elements to be considered in

construction education.

Simulations

and case studies are often included in project management courses. These

educational methods provide a prime opportunity to include subcontract

management problems. Role playing on both sides allow the students to experience

some of the complexity the actual relationship that exists between the

subcontractor and the general contractor.

Change

management and the impact of Owner-Contractor and Contractor-Subcontractor

contract terms and conditions are important considerations in project

management. Likewise the progress payments application and payment distribution

process is critical to a successful General Contractor-Subcontractor

relationship.

In

subcontracting, resource allocation and scheduling is usually a multi-project

task. Likewise, many project managers in General Contracting and Construction

Management firms are involved in multiple projects. Problems developed for

single project application (eg. schedule crashing) can and should be expanded in

scope and complexity address the a specialty subcontractors position on a

multiple project basis. The role of the specialty contractor's project manager

should be one focus of the project management course.

A

well-rounded student will realize the interdisciplinary nature of the industry

and recognize the benefit of a comprehensive understanding of the skills,

abilities and perception required to succeed in speciality subcontracting. It is

valid and valuable to include Specialty Subcontractor project and multi-project

management topic in addition to coverage of the General Contractor's management

of Specialty Subcontractors. Understanding the concerns and methods of the

Subcontractor's project manager will enhance the success of all future builders.

Scheduling Courses

An

examination of the content of a scheduling course might reveal that the

subcontract activities are viewed as a given. Other than mention of the

subcontractor's participation in the development of the schedule and the

necessity for crashing subcontract activities, the scheduling and time

management issues regarding subcontracting are often ignored.

A

review of a realistic construction schedule will reveal both critical and

low-float subcontract activities. There is no doubt that the subcontractors will

influence the project time management. Likewise, the schedule creates certain

obligations on the part of the General Contractor to the Subcontractor. This

topic should receive adequate attention. "The prime contractor has a duty

to schedule work so that the subcontractors will not be delayed in the

performance of their work or forced to perform work out of sequence." [3]

The

scheduling of subcontracted work is essential in establishing an accurate,

accomplishable schedule. While the sequence of the activities may appear

obvious, there are often many factors in specialty contracted work that

substantially impact the project that are not obvious to the casual observer.

The duration estimates for subcontracted activities are critical. The scope of

the work and manpower requirements must be clear and the subcontractor must

commit to furnish the resources when required if the project schedule is to

succeed.

In

many circumstances, the Prime Subcontractor's work is scheduled as a single

activity. Many bar chart show no indication of the impact of key subcontract

work items on other activities or project milestones. Schedule slippage analysis

and/or acceleration decisions must address the total impact on the time and cost

parameters of the project; incomplete planning information will result in

incomplete decisions.

A

schedule that includes the true relationship of subcontract work item activities

to other project activities will facilitate project decisions that will be both

timely and accurate. Required tests and inspections, including subcontracted

work, should be milestones in schedule development. Schedule analysis exercises

should include subcontract activity evaluation.

An

exercise in multi-project labor leveling will provide the students with a

firsthand experience of the resource problems faced by a Specialty

Subcontractor. Material management of long lead items usually involve

subcontractors and can be included in the labor leveling problems to increase

the complexity. In any event, actual manhour requirements for key subcontract

activities and standard crew sizes should be used in duration estimate

exercises.

Scheduling

courses that utilize computer applications can easily accommodate the proposed

exercises. As the computer has become the standard and very useful tool in the

scheduling process, it has also implied a standard for resolution of disputes.

"The widespread use of computerized scheduling techniques has provided new

opportunities in project management and claims analysis including claims of

delay and/or disruptions by the specialty subcontractors." [4]

"Slow

performance by a subcontractor will not excuse the prime's late completion of a

project". [5] Project time management education must provide a

comprehensive address of the coordination of subcontract activities.

Quantity

takeoff and Cost estimating Courses

It

may or may not be feasible to include all specialty contractor work items in the

quantity determination process of the estimating courses. Most courses

ordinarily include the take-off of some items that are typically the

responsibility of a Specialty Subcontractor. The technical courses provide an

excellent opportunity to quantify the work prepared in design assignments that

have typically been intended to demonstrate technical competence.

The

solicitation, receiving, and follow-up of subcontract bids should be a topic of

all cost estimating classes. From the decision to subcontract through the write

up of the scope of work, the student estimator must understand both sides of the

Subcontractor-General Contractor pre-contract phase. The doctrine of

"promissory estoppel" and reasonable reliance to the conflicts

resulting from "bid shopping" should be included in this estimating

education.

It

is, however, most beneficial to have students "price" a (given)

quantity of specialty work to develop a concept of the value of various

components of the project. One method might be to have individual students

responsible for the pricing of different trades resulting in this

"bid" to themselves and other student-general contractors on a

competitive basis against the other student(s) assigned the same trade.

As

a result of the evolution toward subcontracting, the General Contractor's

subcontract bid evaluation and analysis process has an impact on the potential

for project success. An underfunded and/or overloaded subcontractor may not be

able to adequately staff the project with skilled workmen and essential

resources to provide the quality expected nor to meet the time requirements.

Contracts

Courses

While

most construction curriculums contain substantial coverage of the forms and

legal implication of Owner-General Contractor contracts and General Conditions,

the writing of appropriate terms and conditions for General

Contractor-Subcontractor contracts are not addressed in the same depth. The

inclusion of the issues surrounding the subcontracts in courses including legal

and contractual obligation topics is appropriate.

A

contract issued by a General Contractor imposes an legal obligation upon the

contractor to avoid ambiguity and to provide a clear description of the

obligations of the contractor. To often, students perceive that the 16 Divisions

of CSI facilitate the division of work to the specialty contractors. "It is

well established that project owners have no obligation to arrange their

specifications in such a way as to facilitate subcontracting. The prime

contractor has sole responsibility for dividing the work among its subs.

Therefore, there is no substitute for a prime contractor's careful evaluation of

the entire set of plans and specifications prior to allocating work among

subcontractors. If there are any gaps or omissions, it will be the prime's

responsibility to take care of them." [6]

Contract

clauses addressing the, General Contractor's obligation regarding the

relationship of payment to subcontractors to payment by the owner are critical.

"Condition precedent" payment clauses must be understood by both

parties to the General Contractor-Subcontractor agreements.

Changes

and claims are other sensitive issues. The contractor often develops a

"flow down" clause that includes rights and recovery dependent on the

contractor's subsequent claim against the Owner. Recognizing the importance of

the Owner-Contractor relationship, a potential conflict of interest in

supporting the claim can be detrimental to the subcontractor.

From

the subcontractors position, a clear understanding of all contract terms,

wording and potential for negotiations of conditions including hold harmless and

indemnity, flow-down clauses, payment and retention terms, warranties and call

backs, schedule of work, delays and liquidated damages, lien and bond rights,

and of course scope of work including any contingent or pre-conditioned bids.

The American Subcontractors Association's manual "Winning the Battle of

Subcontract Forms" is an excellent reference for educators in need of in

depth information.

Negotiation

and coordination for changes in the project (change management),

schedule/delay/acceleration, and termination are important to both general and

specialty subcontractors. Education exercises that provide application of

decision principles will benefit the student as either future contractors or

subcontractor.

Learning

Needs and Opportunities

All

students entering the building industry will be involved in specialty

subcontractor relationships either as a General Contractor or as a Specialty

Subcontractor. In many circumstances, their initial and possible long range

success will depend upon their ability to handle the situations arising out of

those relationships.

The

number of Speciality Subcontractors far exceeds the number of General Contractor

and Construction Management firms. The graduates of ASC member schools have

typically been employed by the general construction sector while the specialty

contractor group has had to develop managerial staff either through the trades

or from engineering, or non-technical college graduates. One conclusion might be

that the ASC graduate may find a better long-range employment opportunity in a

specialty contracting firm.

CONCLUSION

Project

Management in the building industry is, to a large degree, subcontract

management. A review of text and reference materials provides little, if any,

address of subcontract issues. Given that the success of the project relies on

the performance of subcontractors, then certainly the critical issues in General

Contractor-Subcontractor relationships and potential conflicts merit course

coverage.

There

are two distinct issues in evaluating the education requirement regarding

subcontract management. The first is the management of subcontractors and

subcontracted work by the General Contractor. The second is the managerial

techniques applied and problems incurred by the Subcontractor in the execution

of the contracted work.

The

Authors suggest that coverage of the role and requirements of the Subcontractor

from both the technical and managerial perspectives are essential responses to

both issues. The impact of subcontractor decisions and performance will

influence the success of all graduates entering the construction industry.

Future general and specialty contractors will benefit from a comprehensive

education.

It

is imperative that educators take advantage of the opportunities that are

available in existing courses to provide an adequate understanding of

subcontracting issues from the Specialty Contractor's position. It is easy to

overlook the fact that the pertinent

issues in General Contractor-Subcontractor relations are viewed and approached

differently from each side of the relationship. Expanding coverage of these

perspectives and approaches will better prepare the student to enter the

building industry.

REFERENCES

|