(pressing HOME will start a new search)

- ASC Proceedings of the 25th Annual Conference

- University of Nebraska-Lincoln- Lincoln, Nebraska

- April 1989 pp 74-83

|

(pressing HOME will start a new search)

|

|

REDUCING CONSTRUCTION-RELATED INJURIES AND THEIR COSTS

|

Hank Mol and Steve Williams Auburn University Auburn,

Alabama |

| In

the spring of 1988, the Department of Building Science at Auburn

University received a grant from several construction companies in the

Southeast to do research in construction

safety. The grant was given to develop and analyze a computerized

database of information on construction related injuries in 1987

provided by four relatively large Alabama construction companies. From the resulting database of

nearly 600 accidents and more than 10,000 individual data, the frequency

and severity of accidents were related to such parameters as age of

workers, craft, time of day, day of week, accident cause, body part,

type of injury, and insurance costs. The construction tasks and

environmental conditions on which corrective measures are likely to

yield the highest return on investment as well as specific

recommendations for reducing severity and frequency of accidents are

presented. KEYWORDS: Construction,

Safety, Database, Accidents, Injuries, Workmen's Compensation. |

INTRODUCTION

It

can be argued that construction companies have a moral obligation as well as a

legal responsibility to provide a safe working environment for their employees.

However, even if these issues are not considered, simple economics dictate that

careful and continuous consideration be given to construction safety.

Accidents

cost the construction industry over 9 billon dollars every year [1]. Workmen's

compensation insurance rates have increased dramatically in the past few years,

and evidence indicates that this trend toward increasing rates will continue and

very likely accelerate [2].

There

is a direct and substantial monetary gain that can be realized by reducing the

number and severity of construction accidents. Ideally, corrective actions

should be directed so that they yield the highest benefit to cost ratio.

Unfortunately, many contractors are not aware of the specific areas where their

safety performance could and/or should be improved. The focus of this study was

to analyze existing accident data, identify specific problem areas, and make

recommendations that will likely yield a high return on investment.

ECONOMIC

IMPACT OF ACCIDENTS

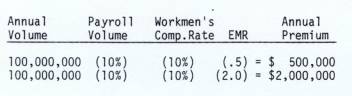

The

economic impact of accidents can best be discussed by way of a short example. Suppose a contractor has an annual volume

of 100 million dollars, which would have placed the contractor 220th on the 1988

Enqineerinq News Record top 400 list. Suppose further that the annual

payroll is 10% of this figure, and that the average base rate for workmen's

compensation is also 10% of annual payroll. The annual cost of workmen's

compensation would then be calculated as noted.

Hypothetical

Construction Company

Annual Volume=$100,000,000

Payroll=10% of Annual Volume

Workmen's Compensation Rate=10% of Payroll

Annual

Cost of Workmen's Compensation

($100,000,000) (10%) (10%) $1,000,000

The

base rate for workmen's compensation insurance is modified by what is called an

experience modification rating (EMR). This rating is based on company safety

performance over the past three years. EMR's typically range from 0.5 to 2.0.

For the hypothetical case discussed previously, variation in the EMR from 0.5 to 2.0 would result in annual premiums of either

$500,000 or $2,000,000 as noted.

In

other words, the difference in insurance premium cost for a very poor safety

record versus an excellent one for this hypothetical company is $1,500,000. The

cost of accidents is not just a fixed cost of doing business. It is

a cost over which management has a great deal of control.

INDIRECT

COSTS OF ACCIDENTS

In

fact, the costs described above are just a percentage of the true cost of

accidents. There are indirect costs associated with every accident that occurs

on a construction site. A few examples of these indirect costs are listed below.

|

These

items represent just a few of the many factors that are seldom accounted for

when the cost of an accident is determined. They are often subjective in

nature and difficult to calculate but are nonetheless very real costs that

must be paid by the contractor. Because these expenses are usually hidden in

total labor costs, management does not get an accurate picture of the true

economic damage caused by job-site accidents. Safety experts conclude that it is

conservative to estimate the indirect costs of an accident to be 4 times the

insurance company direct costs. They may be as high as 17 times the insurance

costs [3].

EFFECT

OF ACCIDENT

FREQUENCY ON INSURANCE PREMIUMS

Two

primary factors should be considered when looking at the history of a company's

accidents. These factors are frequency and severity. There is a tendency to

incorrectly assume that accidents which incur only minor costs are unimportant.

When

experience modification ratings are calculated, the frequency of accident

occurrence is much more important

than the severity of the accident [4]. Minor accidents have a major impact on

the amount of money a contractor must pay for workmen's compensation insurance.

RESEARCH

PROCEDURE

Four

large general contractors agreed to supply all relevant safety records for the

1987 calendar

year.

They also agreed to provide corresponding insurance costs wherever possible.

Each of the four companies has an annual volume that places them in the Engineering

News Record top 400 list, and is engaged

primarily in the construction of buildings.

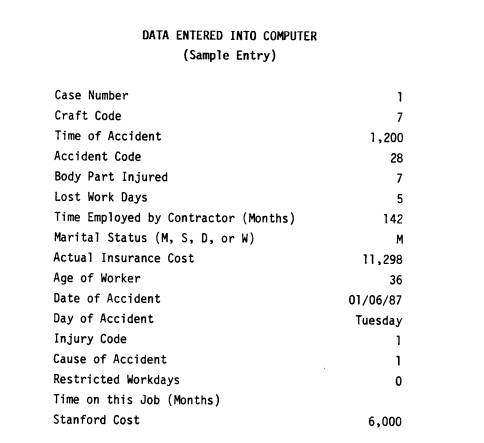

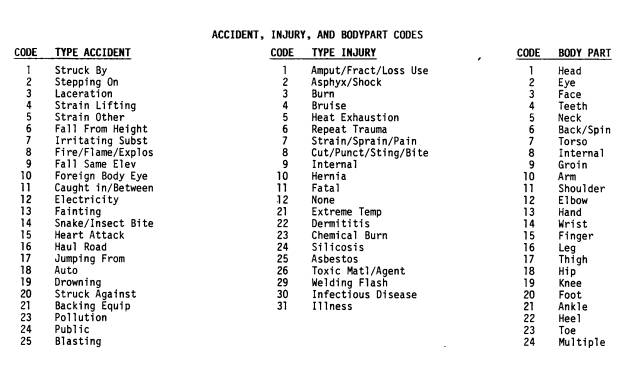

Each

accident report form was analysed in detail

and broken down into 17 different categories. These categories included such

items as age of worker, type of craft, day of week, cause of accident, body part

injured, and insurance cost (see appendix charts Al and A2). A total of 594

accident report forms were catalogued in this

fashion.

After

the forms were analyzed, the more than 10,000 individual data were entered into

a customized computerized database that was developed specifically for this

project.

The

data entry phase was followed by a period of verifying and checking to ensure

that no input errors had been made.

Once

the data were entered and verified, an . extensive and comprehensive analysis

was performed. The data were collated and categorized in a myriad of different

ways. Results of this work will be explained in

the section that follows.

DISCUSSION

ON FINDINGS

Average Insurance Cost

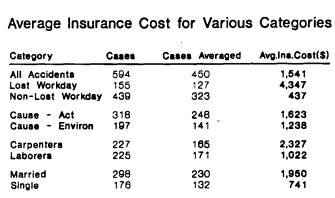

Average

insurance cost was determined considering only those cases for which insurance

costs were available. Most cases were closed. If they were not, the insurance

reserve was added to the cost paid to date.

Analysis

of the research data indicated that the average direct cost paid by the

insurance companies for each injured employee was $1,541. If the employee's

injury resulted in lost or restricted workdays, the average direct cost was

$4,347 (Chart 1). Considering that approximately 35 percent of the insurance

company's premium revenue goes toward their profit and general overhead costs,

the construction contractor's workman's compensation insurance premium cost is

about 1.54 times the direct cost paid by the insurance company for injuries.

This does not consider the impact of the EMR. As stated previously, the

construction contractor may also have indirect costs for accidents that are 4 to

17 times the insurance company direct costs [3].

|

| Chart

1 |

The

average cost of injuries caused by employee acts was found to be 30 percent

higher than

for

injuries caused by the employee's environment. Considering also that 62 percent

of the injuries were caused by employee acts, it is this area that should

receive emphasis for corrective action.

The

average cost of injuries to carpenters was $2,327, which was more than twice the

$1,022 average cost for laborers. This difference nay be caused in part by the

fact that carpenters normally earn higher salaries than laborers. The average

cost for other crafts was not determined because of insufficient sample size.

Married

employees had an average cost per injury of $1,950, which was more than 2.5

times higher than the $741 average cost for single employee. This somewhat

surprising statistic may be partially the result of single employees being

generally younger and less skilled, hence having a lower wage rate.

Time

of Day

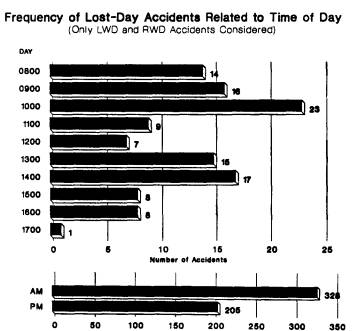

When

all accidents were considered, the data indicated that most accidents occurred

at 10

M,

perhaps because the job's production intensity is greatest at mid-morning. The

data also showed that there were about 60 percent more accidents in the morning

than in the afternoon (Chart 2).

|

| Chart

2 |

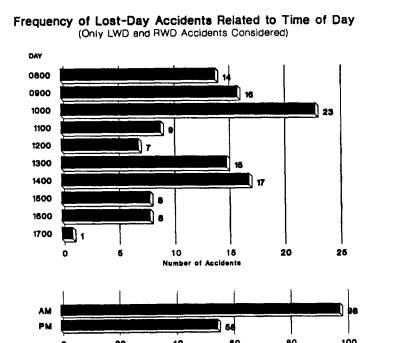

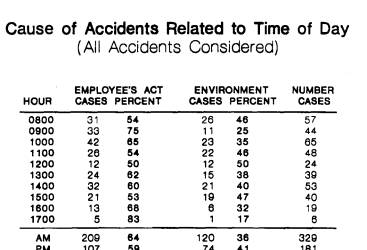

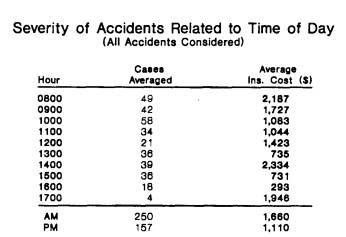

Analysis

of accidents which resulted in lost or restricted workdays showed the same trend

(Chart 3). It is interesting to note that the data does not support the common

notion that accidents occur at the start and ending of the workday. The

percentage of accidents caused by an employee's act increased slightly at

mid-morning and again late in the day (Chart 4). The average insurance cost per

injury was 50 percent higher in the morning than the afternoon, which suggests

that the more serious accidents occur in the morning (Chart 5).

|

| Chart

3 |

|

| Chart

4 |

|

| Chart

5 |

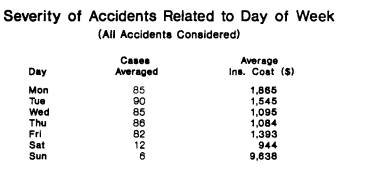

Day of Week

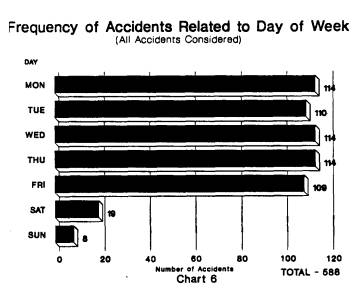

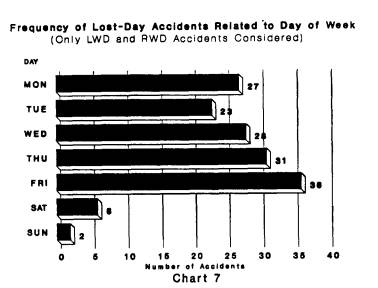

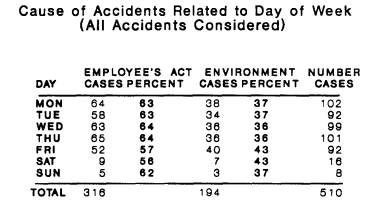

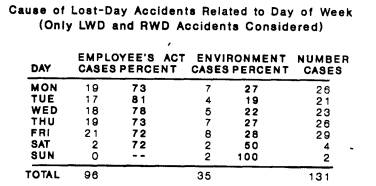

Accidents

occurred with approximately the same frequency for each day of the week (Chart

6),

but

there was a trend for more lost or restricted workday accidents to occur on

Friday (Chart 7). Approximately 60 percent of the accidents were caused by an

employee's act regardless,of the day of week (Chart 8). However, employee's acts

caused over 70 percent of the lost-day accidents, while again showing no

significant difference between the days of the week (Chart 9). The average

insurance cost paid per injury was highest on Monday at $1,865, decreased as the

week progressed, and then rose on Friday to $1,393 (Chart 10).

|

| Chart

6 |

|

| Chart

7 |

|

| Chart

8 |

|

| Chart

9 |

|

| Chart

10 |

Employee

Age

The

number of accidents was determined for various age groups, but without knowing

the age mix in the workforce, the frequency or propensity for accidents in any

group could not be determined (Chart 11). Research by others has shown that

worker's age has no relation to incidence of injuries [5].

| Frequency

of Accidents Related to Age of Worker (All Accidents Considered)

|

| Chart

11 |

The

severity of accidents relative to age group, when measured by average insurance

cost paid per injury, increased with age to age-group 30 to 34 (Chart 12). The

increase in cost is influenced by the likely increase in workmen's compensation

benefits generally paid to older workers due to their higher skill and wage

rates. The relatively small sample sizes below age 20 and after age 34 precluded

reliable results for those age groups.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chart

12 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

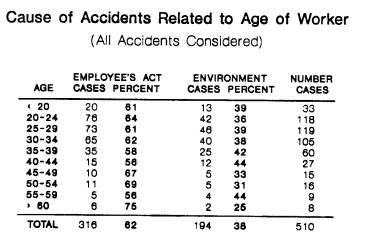

The

cause of accidents, act versus environment, showed no significant difference

between age groups. The total sample showed that 62 percent of the accidents

were caused by employee acts (Chart 13).

|

| Chart 13 |

Time

Employed and Time on Job

The

number of accidents decreased as time on the job and time employed by the

contractor increased (Charts 14 and 15). Although it may be that workers new to

the job or new to the employer are more likely to have accidents, the data could

not be used to support that conclusion because the mix of the workforce relative

to time employed and time on the job was not known. Other research has shown

that frequency of job-related injuries is directly related to employee turnover

[6].

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Chart

14 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Chart

15 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The

data did not show a relationship between average cost of accidents and time on

the job or

time employed, possibly because of inadequate sample size. This was caused in

part by these data not being provided in some of the accident reports or by

having to discard time on the job

for some cases where it was obviously entered erroneously in the accident

report. The data did show that there was no relationship between cause of

accident, act versus environment, and time

on the job or time employed by the contractor.

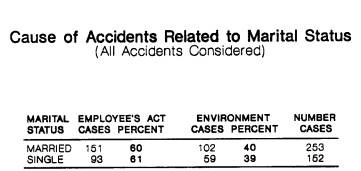

Marital

Status

The

marital status of the injured employees was recorded, but the propensity for

accidents for married versus single could not be determined without the mix of

married and single in the workforce. However, other research has shown that

frequency of injuries is not related to marital status [5]. It was found that

the cause of accidents was about the same for married and single employees, 60

percent acts and 40 percent environment (Chart 16).

|

| Chart

16 |

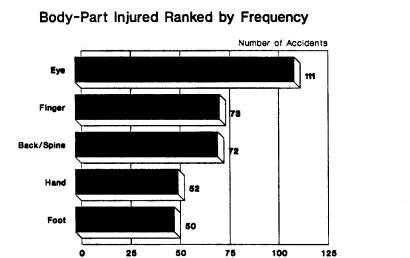

Most

Frequent Accidents

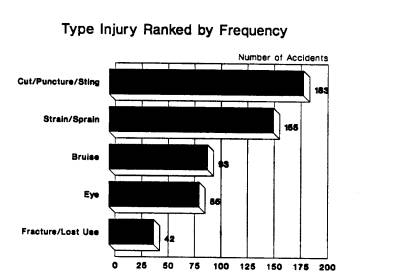

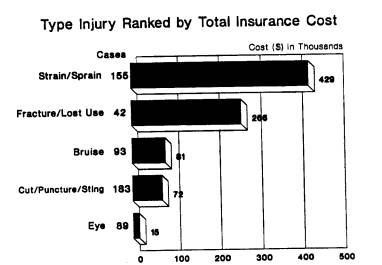

The

most frequently occurring accidents, bodyparts injured, and type injuries are

shown in charts 17 to 19. Frequency of accidents and injuries, regardless of

average cost, is an important consideration when determining priorities for

corrective action to lower insurance cost because of its impact on premium

rates. As stated previously, the experience rating plan for workman's

compensation insurance premiums gives greater weight to accident frequency

than to accident severity.

|

| Chart

17 |

|

| Chart

18 |

|

| Chart

19 |

After

examining the more frequent accidents, it became apparent that some of the

categories, such as accidents where an employee was struck by an object or where

injuries resulted in cuts, puncture, sting or bite, were too broad to focus on a

particular corrective action without further category breakdown. However, the

category "foreign body in the eye" has a relatively high frequency, 89

cases out of the 594 total cases, and is sufficiently specific to allow focus on

a corrective action. Other categories of this type are strains due to lifting,

48 cases; cut fingers and hands, 49 cases; and foot punctures, 29 cases.

Increased

emphasis on proper lifting technique would certainly lower the back-strain cases

which are 70 percent of the strains due to lifting. The wearing of proper eye

protection, gloves, and steel-soled shoes would considerably lower injuries to

the eyes, hands, and feet, possibly by as much as 50 percent. When examining

lacerated hands alone, it was estimated that 70 percent of those injuries would

have been reduced or eliminated by wearing gloves. All of the foot punctures

would probably have been eliminated by the wearing of steel-soled shoes.

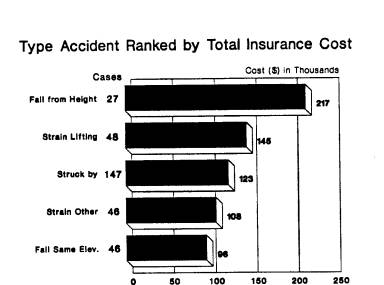

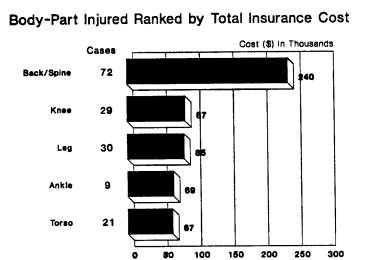

Most Costly Accidents

The

most costly accidents, body-parts injured, and type injuries, as determined by

multiplying number of cases by average direct insurance cost per case in each

category, are shown in charts 20 to 22. Since the ranking by total insurance

cost considers both frequency and severity, it too is a good indicator for determining

priorities for corrective action.

|

| Chart

20 |

|

| Chart

21 |

|

| Chart

22 |

Falls

from height were found to be the most costly type accident. Thirty-one percent

were from scaffolds, often improperly secured. Wet or muddy conditions caused 25

percent of the falls at the same elevation. The diversity of causes suggest only

that workers be trained to be more aware of their environment, and that foremen

pay more attention to providing a safe working environment.

STANFORD

ACCIDENT COST ACCOUNTING SYSTEM

Each

accident was analyzed to determine an estimated cost using the Stanford Cost

Accounting System [7] and entered into the computer for comparison with

insurance company direct costs. It was hoped that a correlation would be found

which would allow modification of the Stanford Cost Schedule to account for

inflation and allow a recommendation for its use as a predictor of accident

costs. However, a correlation was not found, probably because the data base was

too small. Nevertheless, construction companies should look for ways in which

the cost of accidents might be considered in determining the profitability of

individual jobs and in rating the performance of job superintendents.

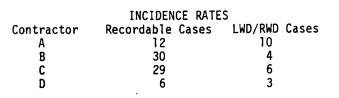

INCIDENCE RATES

National

and state averages are published which list the frequency of OSHA reportable

injuries and illnesses and on the frequency of those cases with lost or

restricted workdays. The incidence rate for OSHA reportable cases in

non-residential building construction in Alabama for 1985 was 21.0 cases per 100

full-time employees [8]. The incidence rate for lost and restricted workdays (LWD/RWD)

in Alabama that year for the same workforce was 7.6 cases. Contractors should

compare their company's incidence rate with the state and national rates, but

they should also recognize that different contractors interpret what is an OSHA

reportable case in different ways. This will influence the company's

incidence

rate. The incidence rates calculated for the four construction companies using

the data provided were as follows:

Are

these incidence rates good for comparison of the company's accident experience

with state or national rates? Probably not. Contractor A's LWD/RWD incidence

rate indicates a high accident rate, but the recordable case incidence rate

shows an excellent record. It is possible that contractor A did not interpret

many of the minor recordable cases as being recordable. Contractors B and C have

good lost workday rates but poor recordable case incidence rates. It is likely

that they recorded cases that need not have been recorded. Contractor D has such

excellent incidence rates for both categories, that they are questionable. It

could be that the reported manhours were more than the work activity for which

accidents were considered.

COMPANY

SAFETY PROGRAMS

Since

formal safety programs have been credited with helping lower injury rates in

construction [9], the written safety programs for each of the four companies

submitting accident data were requested for review. Only one of the four

submittals was considered a comprehensive company safety program. One of the

companies submitted a job safety plan similar to that required on Corps of

Engineers contracts, one submitted an excellent safety booklet provided to their

craftsmen, and one submitted the AGC manuals on accident prevention and OSHA

compliance. Although the latter three submittals represented excellent aspects

of a company safety program, they were not in themselves sufficient in providing

a comprehensive company safety program.

The

most important action that a construction company can take to reduce accidents

is to establish a policy that makes the safety of its employees as important, if

not more important, than production. This policy should be in writing, signed by

the CEO, and communicated to all personnel with the understanding that

compliance is a condition of employment.

For

a large company, a comprehensive safety program should include written

descriptions of the responsibilities of all personnel as they relate to

safety, a project safety requirements planning checklist, employee safety

procedures and requirements, safety inspection and accident/incident

investigation checklists and procedures, accident emergency procedures,

accident/illness reporting and recordkeeping procedures, employee craft skills

and safety training, safety motivation program, and subcontractor safety

requirements. A study in 1980 indicated that the cost of administering a

construction safety program amounts to about 2.5% of direct labor cost. The

ratio of savings to the costs of administering the program was found to be 3.2

to 1 [3].

A

vital aspect of a construction company's safety program is the analysis of

safety hazards found on inspections and investigations, and follow-up to insure

that corrective action has been taken. A systematic approach is

necessary

to be effective and will show management's true commitment to safety. The

National Safety Council has published an excellent booklet describing a

relatively new and detailed approach to correction of hazards [10].

RECOMMENDATIONS

Wear

Eye Protection

Many

companies involved in manufacturing require that safety glasses be worn by

employees when they are in or near the process areas, essentially eliminating

eye injuries. Yet, for some reason, few workers in the construction industry are

required to wear eye protection.

Eye

injuries comprised 19% of all the accidents that were logged. Most of these

accidents were avoidable. Although the average cost for these injuries was

relatively low, a company's experience modification rating (EMR) is more closely

tied to the frequency of accidents rather than severity. Therefore, the true

cost of these accidents is considerably higher than the average cost of $173 per

case.

Require

Proper Hand and Foot Protection

We

recorded a large number of lacerations and puncture wounds to hands and feet.

Many of these accidents could have been avoided by wearing gloves and/or safety

boots with steel toes and steel soles. Although some may argue that gloves may

be cumbersome when working at some tasks, their use would greatly decrease

injuries to the hand and should be considered. There is no justification for not

wearing safety shoes.

Use

Proper Lifting Procedures

Among

the most costly accidents are those involving back injuries when lifting. All

superintendents should be aware of proper lifting techniques and should educate

workers on proper lifting techniques through toolbox meetings or other training

methods. While these accidents can never be eliminated, their frequency can be

reduced with a proper educational program.

Be

Aware of Environment

A

suprisingly large number of accidents occurred because a worker slipped on a

slick surface. Muddy, oily, or slick surfaces should serve as a red flag to

superintendents, and workers should be cautioned accordingly.

Establish

a Comprehensive Safety Program

Beyond

the moral and legal responsibilities that a construction company has for the

safety of its employees, economic interests dictate the desirability of a

comprehensive safety program. All large construction companies should establish

a written comprehensive company safety program to include:

|

Keep Better Records

While

gathering data from the accident report forms, we were hampered by the

inconsistancy between forms from different states, the sometimes inadequate

description of the cause of the accident and the extent of the injury, and

occasionally the incomplete or erroneous entries in the forms. If company

executives are to achieve an effective safety program, they must be able to

monitor the type and frequency of accidents that are occurring. Project

superintendents should be required to fill out a detailed form in addition to

the required OSHA or insurance form. Upon reaching the main office, the data

from these forms should be stored in a computerized database, so that they might

be organized and categorized for further analysis.

Include Safety Performance in Evaluatinq Superintendents and Job Profitability

Since

the safety record of a company affects its profitability, and since personnel

are often provided bonuses based on their contribution to profitability, it is

recommended that some measure of the cost of accidents be considered in

evaluated performance. One such method might be to use the direct cost paid by

the insurance company plus any reserve set aside for accidents occurring on a

project. The true cost of the accidents may be considerably higher than this

cost. Some of the cost is already charged to the job in lost productivity,

rework, and overhead charges, and some of the cost will show up on future jobs

in the form of higher insurance premium cost. However, much may be gained by

drawing attention to the economic aspect of safety.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The

authors wish to extend sincere gratitude to Mr. Steve Belflower, student

research assistant, for the excellent job he did in assisting with the

gathering and analysis of data for this report. In addition, we wish to thank

industry members Jim Rein, Robin Savage, Jim Gorrie, and Ben Nevins for

providing their time and the mass of information upon which this report is

based.

Lastly,

a very special thank you to Mrs. Jane Parrotte for her endless patience and her

excellent advice regarding the preparation of

this document. She is a unique and invaluable asset to the Department of

Building Science.

REFERENCES

1.

The Business Roundtable, Improving Construction Safety Performance,

200 Park Avenue, New York, N.Y., January 1982.

2.

"Premiums Pulse Upward for Workers' Compensation," ENR,

September 15, 1988, p. 58.

3.

"Improving Safety Helps Improve the Bottom Line," Civil Engineering,

ASCE, October, 1982, p. 48.

4.

National Council on Compensation Insurance, An In-depth View of Experience

Rating, One Penn Plaza, New York, N.Y., 1982.

5.

Hinze, J., "Human Aspects of Construction Safety," Journal of

the Construction Division, ASCE, Vol. 107, No. COI, March, 1981, p. 63.

6.

Hinze, J., "Turnover, New Workers, and Safety," Journal of the

Construction Division, ASCE, Vol. 104, No. C04, December, 1978, p. 412.

7.

Levitt, Raymond E. and Samelson, Nancy M., Construction Safety Management,

McGraw-Hill, New York, N.Y., 1987, p. 30.

8.

Alabama Department of Labor, Alabama Occupational Injuries and

Illnesses Survey 1985, 64 North Union Street, Montgomery, Alabama.

9.

Hinze, J. and Harrison, C., "Safety Programs in Large Construction

Firms," Journal of the Construction Division, ASCE,

Vol. 107, No. C03, September, 1981, p. 464.

10.

National Safety Council, Accident Investigation ...A New Approach,

444 North Michigan Avenue, Chicago, Illinois, 1983.