(pressing HOME will start a new search)

- ASC Proceedings of the 25th Annual Conference

- University of Nebraska-Lincoln- Lincoln, Nebraska

- April 1989 pp 44-48

|

(pressing HOME will start a new search)

|

|

CONSTRUCTION

FINANCE MODELING FOR INCOME PROPERTY

|

Francis

M. Eubanks |

| This

discussion will cover financial modeling for income producing properties

in the built environment. Such properties include apartment projects,

motels, hotels, strip shopping centers, regional shopping malls,

office parks, professional parks and multi-story office building

complexes. The objective is to introduce

and inform the reader about financial modeling for Value By Income

Approach analysis and Income Feasibility (rate of return) analysis

techniques. These two very powerful tools are in various stages of use

and refinement by both lenders and owner-developers alike. These

techniques, and their underlying principles, have many applications in

decision making that drive the development, design, general contracting

and construction management processes. Basically, Value By Income

Approach involves assigning a dollar value to a property based on its

ability to produce income and Income Feasibility involves calculating a

before tax rate of return on the owner's or owner-developer's cash

investment in a property. |

INTRODUCTION

It

is unlikely that a developer will have the cash equity to construct his project

without borrowing. Even if he did have the cash, he would still resort to

borrowing in order to leverage his own funds so as to increase his rate of

return. Also, in order for the general contractor to be successful in borrowing

short term funds, when needed, to meet payrolls and material invoices, he

frequently must demonstrate that the owner or owner-developer has a firm

construction loan enabling him to pay the monthly draws. It is, therefore,

generally necessary that an owner or developer secure a loan commitment prior to

obligating himself to a contractor, construction manager, or even an architect

for any substantial amount of dollars.

Before

making loan commitments, lending institutions examine the owner's or

owner-developer's balance sheet and revenue and expense statements as well as

his record of experience with similar projects in order to determine his

financial strength and stability. In addition, the project itself has to be

examined in terms of its ability to pay for itself and make a reasonable rate of

return for its owner. This latter examination involves some model for valuation

based on income production and some model for projecting a rate of return.

When

an individual desires to finance a home using a purchase money mortgage, the

lending institution evaluates his net worth as well as the cost (and comparable

market value) of the home being financed. However, the lending institution also

examines the individual's income and expense stream in order to determine the

individual's ability to make his monthly payments. Value By Income Approach will

be seen to be a highly similar technique.

Lending

institutions do not want to become owners by virtue of the borrower's default.

They are in business to collect interest on loans. Lenders seek evidence that

the project itself will provide the owner or owner-developer with the necessary

proceeds to retire the loan as well as an attractive rate of return. Lenders

therefore need tools for evaluating projects based on the expected income and

expense streams for those projects.

THE

METHOD

There

is no substitute for a thorough analysis of: (a) current market needs; (b)

current and planned construction activity; (c) current rental rates and vacancy

rates; (d) population movement; (e) the availability of transportation, schools,

shopping and recreation; (f) accurate estimates of site development costs and

construction hard and soft costs. All of these items must be meticulously dealt

with in a feasibility study. The valuation of a project based on its income

production potential can only be a "capstone" for a thorough

feasibility study.

The

capstone model includes a "Project Value by Income Approach"

calculation which, typically, is the "Value" in a "Maximum Loan

To Value Ratio" (generally 80%) used to determine the maximum loan amount.

Once the maximum loan amount is determined, a calculation called "Income

Feasibility" (rate of return) is made.

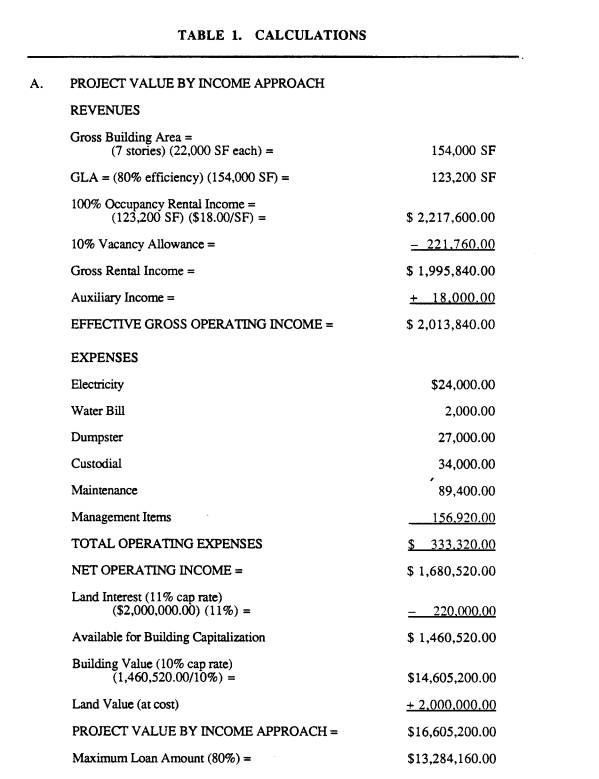

The following case study calculates a Project Value By Income Approach (Part A) for an assumed midrise office building and then summarizes actual Replacement Cost (Part B) for the same project. Income Feasibility (Part E), which draws upon most of the same data plus debt service, is used to compute a "cash on cash" rate of return (cash coming out as pre-tax profit divided by the amount of cash equity the owner or owner-developer had to take out of his own funds to construct the facility). The rate of return so generated may be likened to the rate of interest earned on the owner's or owner-developer's investment. If a better rate of return could be earned on some other investment, or a similar rate of return on a "safer" investment, the project might never be built. If appreciation is likely, we might do well to consider it (Part F).

CASE STUDY

Kenny

Mothy and Rick Ford have applied for a loan to develop a midrise office

building. It is necessary to determine the (A) Project Value by Income Approach,

(B) Replacement Cost, (C) Maximum Loan Amount Available, (E) Before Tax Rate Of

Return, and (F) Appreciated Rate of Return after one year of operation using 5%

appreciation per year.

The

project is to be a seven story office building with 22,000 SF per floor with a

Gross Leasable Area (GLA) equal to 80% of Gross Building Area. Market analysis

indicates a rental rate of $18.00/SF per year and a Vacancy Rate of 10%. The

building includes a spa and health club which are expected to produce Auxiliary

Income of $18,000.00/year.

Electrical

power bills are to be prorated on a square footage basis with Rick and Kenny

picking up an estimated cost of $24,000.00 per year to cover "public

areas" and unoccupied spaces. Rick and Kenny are to pick up the entire

water bill, estimated at $2,000.00 per year and the dumpster, estimated at

$2,700.00 per year, as well as custodial expenses for all "public

areas," estimated at $34,000.00 per year, and maintenance of "public

areas" estimated at $89,000.00 per year. Rick and Kenny estimate management

expenses (including payroll, property taxes, insurance, supplies, etc.) to be

$156,920.00 per year.

The

lender's current terms are 10%, compounded monthly, on 30 year loans and

capitalization rates are 11% for land and 10% on improvements. Maximum loan

amount is smaller of 80% of Value By Income Approach or 85% of Replacement Cost.

Construction

cost is $85.00 per square foot, including Architect fees. Brokerage fees, loan

discounts, closing costs and property tax during the construction period are

estimated to be $213,000.00. Construction Loan Interest (which will be rolled

into the permanent loan) is estimated to be $975,000.00.

EXPLANATIONS

Project

Value By Income Approach (Part A): A value is placed on the project by

"capitalizing" its Net Operating Income. Usually, land cost and

building cost are capitalized at different rates since they involve different

risk factors.

A

"capitalization rate" is essentially a lender prescribed interest

rate. Annual Net Operating Income is divided by the capitalization rate to

determine Project Value (much as annual interest divided by interest rate equals

principal).

Revenues

(income items) are estimated and combined and Expenses are deducted to arrive at

Net Operating Income. Net Operating Income is the amount available to pay taxes,

the mortgage, and profit.

The

capitalized value of the project's Net Operating Income is its Value By Income

Approach. In our case study, the lender will loan a maximum of 80% of this

value.

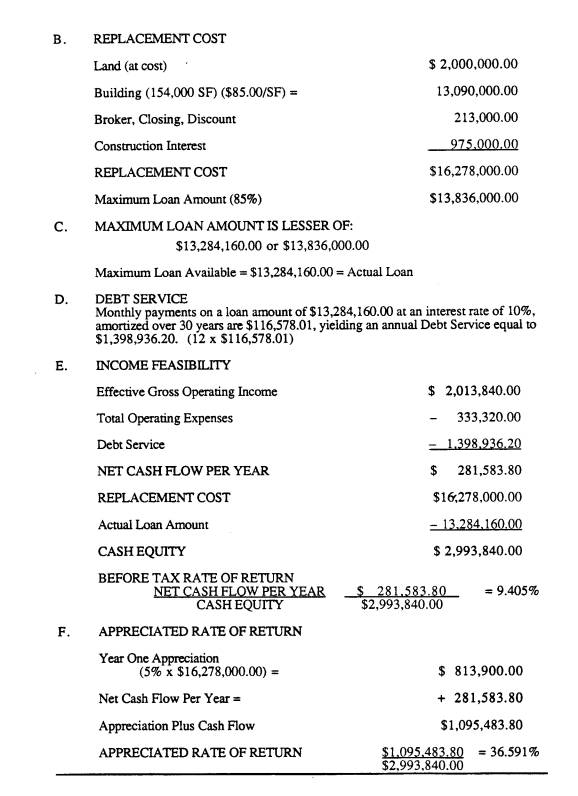

Replacement

Cost (Part B): This is the actual cost of producing the project. It includes all

construction costs, land costs, interest accumulated during the construction

period, architect fees, loan closing and loan brokerage fees, tenant allowance

costs, all costs that must be paid to produce the project. The lender will

usually require the borrower to pay a certain minimum percentage of this cost

from his own funds (else, the borrower might borrow more than it costs to

construct the project). In our case study, the lender has set 85% of this value

as a maximum loan.

Maximum

Loan Amount (Part C): Note here that, in our case study, the Value By Income

Approach exceeds the Replacement Cost. In other words, the value of our project

as an operating entity exceeds the cost of creating it. Traditionally, a Loan To

Value Ratio was applied to the (lower of) Replacement Cost (or to adjusted sales

prices of recently sold "comparable" properties) to determine maximum

loan amount. The introduction of Value By Income Approach has created an

interesting dilemma which has often resulted in owners or owner-developers being

able to borrow a higher percentage of cost for their projects.

Income

Feasibility (Part E): Here we go back to the Net Operating Income from Part A

and subtract the amount actually required (Part D) to make the mortgage payments

(note that we still have not allowed for taxes or profit) to arrive at an income

comparable to income from other forms of investment. We then divide that income

by the actual amount of dollars the owner put into the project from his own

funds. This is a "cash on cash" return, similar to cash interest

received on a cash investment in a savings account.

Appreciated

Rate of Return (Part F): Most real estate developments do appreciate in value.

In our case study, the basic Before Tax Rate Of Return was a rather poor 9.49%.

The owner or developer might do well to put his money into some lower risk

investment and forego construction of this project. However, the Appreciated

Rate Of Return, 34.49% (assuming a holding period of one year), illustrates the

magic of leverage often available in real estate development.

CONCLUSION

The

Project Value By Income Approach and Income Feasibility Analysis can be very

powerful tools for both lender and borrower alike. Traditionally, valuations

have been made in terms of Replacement Cost or what appraisers believe to be

"comparable properties" with no consideration given to income

producing potential. The analysis made no serious effort to recognize that it is

the income stream produced by the property that ultimately pays the mortgage and

produces income for its owner. These two tools, by design, relate the value of

the property to its ability to retire its own mortgage and provide a means of

measuring the property owner's rate of return on his investment.

Inasmuch

as an income producing property is constructed, bought or sold for the purpose

of producing income, a method of measuring its value based on that income and

measuring the expected rate of return, also based on that income, is essential

to the industry. These two tools respond to that need.

It

can be seen readily in observing the calculations that accuracy in determining

Value By Income Approach and in projecting Income Feasibility is heavily

dependent upon the reliability of the data used. Use of these models, therefore,

should be limited to those entities who have the necessary resources to gather

or purchase quality data.

|

|

REFERENCES

|