- ASC Proceedings of the 40th Annual Conference

- Brigham Young University - Provo, Utah

- April 8 - 10, 2004

|

A Working Model for Funding Construction Management Programs

Public universities in the United States face the challenge of how to maintain quality, conduct valuable research, and contribute to the well being of the larger society, while experiencing significant budget reductions. Discerning faculties and administrations turn to new models for securing funds. At Arizona State University, a recently appointed president drives the organization to the new models rapidly. The University’s Del E. Webb School of Construction has embraced the challenge and has instituted, as part of its fund-raising activities, a funding model parallel to the endowment search -- a two-track approach that seeks discretionary funds while pursing the traditional university endowment funds. This paper presents a working model for consideration by university construction programs as they seek funds to replace diminishing resources. The objectives of the model include maintaining and then elevating the current level of program quality, providing discretionary funds for the program director to establish a great organization, supporting faculty and program development that supplements the endowment base, and moving the School from a state-supported to state-assisted entity.

Key Words: Funding Model, Discretionary Funds, Construction Management Programs

Introduction

Funding distributions at Arizona State University’s Del E. Webb School of Construction are based on historical data and are subject to the university’s budget review decisions in the state legislature. In addition, funding levels are subject to the usual unit and political realities at the college level. The net effect is that the academic year begins and the School’s Director does not know what the final funding level will be. Many experienced administrators at the university establish a planning budget in the fall of each fiscal year, review and adjust in January, and balance the budget by fiscal year end. In the 2002-03 fiscal year, this budgeting process was influenced by two critical events: the state legislature cut funding to higher education, and “payouts” from the university foundation endowment accounts were delayed. These simultaneous events created substantial anxiety and uncertainty. The reality is that this scenario may no longer be the exception in this university’s funding cycles. Units at ASU that embrace the current model may fade away in the “New American University,” a phrase ASU’s new president has adopted to describe his vision for the institution. Changes in funding models are inevitable.

In many universities officials turn to private sector terms such as “enterprise” and “entrepreneurial” to declare their intention to do things differently in their pursuit to remain whole financially. Public institutions can not practically pursue profits, so the issue becomes one of adapting the private funding model to the university setting. Kozicki (2003) provides an excellent discussion regarding the new vocabularies for university enterprise models.

The authors of this paper suggest that there is no university unit more equal to the challenge, or better positioned, save for the college of business, than the construction program. Simply stated, liberal arts, sociology, and the like, are hard-pressed to approach their industries for support. On the other hand, the construction industry accounts for 8% of the gross domestic product and nearly a trillion dollars of revenue per year, a fertile and supporting environment in which to move from a state-supported to a state-assisted program. By way of example, consider the following. The value of construction put in place in the United States set a sixth straight seasonally adjusted record in December 2003, at $933 billion at an annual rate (U.S. Census Bureau, 2003). At Arizona State University, the Del E. Webb Foundation and Ira A. Fulton, both out of residential construction, recently totaled nearly $60 million in endowments to the School of Construction and to the renamed Ira A. Fulton School of Engineering. The Peter Kiewit Foundation in Nebraska has donated more than $400 million statewide since its inception. Of that total, nearly $44 million has been contributed to the University of Nebraska, including a $15 million grant for a state-of-the-art facility to create what is now called The Peter Kiewit Institute of Information Science, Technology and Engineering on the University of Nebraska at Omaha campus (University of Nebraska Medical Center, 2004).

Regarding the Del E. Webb School of Construction, it received a $4 million endowment in 1992. This provided a base for gifts, donations and endowments that has grown to its current $10 million. With the initial endowment, the School’s program leader established a philosophy and action and strategic plans that promoted self-support and funding flexibility. In 2001, with industry support and prompting, the program director hired a full-time development officer to be responsible for establishing a funding mechanism for a $50 million capital campaign. This position became the only development officer, among 46 at Arizona State University, below the college level. Furthermore, the industry and the program director funded the position entirely, whereas all other development positions were funded from a number of sources, including the deans’ offices and the university foundation. Finally, the incumbent was charged with covering his own salary within two years. This scenario of risk, on the part of the program director, the industry, and the new development officer, was the first and necessary milestone set in place in the funding model.

The DEWSC Model

In 2001, the Del E. Webb School of Construction (DEWSC) turned to a business model for raising money that is not tied exclusively to endowment requirements. DEWSC has adopted a two tier system for raising funds. One of the tiers has as its specific objective to establish a revenue stream that provides the program director with discretionary funds needed to stimulate the entrepreneurial environment.

The underlying driver of this model is to achieve a 3 to 1 source of revenue; that is, for every dollar of state money received, the School will generate three dollars from other sources, such as research, professional development and continuing education programs, gifts and endowments, and non-traditional education endeavors (distance learning, international initiatives, etc.). By default, faculty and administrators must become “entrepreneurial” to achieve this revenue ratio.

As a caveat, total discretion in the use of funds (not state awarded) is impractical – for example, endowment agreements often preclude discretion at the unit level. Nevertheless, it is possible to ensure that most of the 3-1 funds are discretionary. Additionally, the argument can be made that it is mandatory that most of the funds be discretionary when one considers that the Arizona State University President’s ultimate ratio (other sources to state revenue) is 10-1. The DEWSC model can best be described as one of moving to being “state-assisted” from “state-supported,” ultimately at the 10-1 ratio.

Tier One: Traditional Fundraising

A brief description of the School’s traditional fundraising efforts is in order, to put the two tier approach into perspective.

DEWSC established a capital campaign goal of “$50 million by 50,” based on the School celebrating its 50th anniversary in 2007. A capital campaign committee was formed comprised of industry donors and program alumni. This group represented endowment gifts of $3 million and annual cash donations of over $300,000, which are not tied to specific endowment requirements.

The campaign has as its objectives establishing 10 professorships ($500,000 each) and one endowed chair ($2 million), doubling research dollars to $6 million (sponsored research is considered in the university’s fund-raising count), increasing diversity through grants and gifts, and funding a building dedicated to the construction management program. Figure 1 in Appendix A displays one type of professorship in the campaign, called the “5-Year Professorship.” In this case, the donor can spread his or her gift over five years, with the option of stopping the donation at any time. Based on the cyclical nature of the construction business, this provides flexibility for a donor to give without committing to half million dollars at one time. In the event the donor is unable to fulfill the entire commitment, any donation already received at that point remains with the School. The example shows how funds are dedicated in each of the five years. Other professorships are the “10-year Professorship” (same premise spread over 10 years), and the “External Control Professorship,” wherein the donor retains control of the endowment “corpus” and pays out interest directly, rather than placing the funds in the university’s foundation. The professorships, and other endowment objectives, are pursued in the traditional fashion known to fund-raising in higher education.

Tier Two: Discretionary Funds

DEWSC took two actions to initiate the pursuit of discretionary funds. First, it hired an individual experienced in business (in the construction industry) as its development officer. Secondly, it established a cash flow committee, whose members include several from the School’s Industry Advisory Council, and who serve as a kitchen cabinet to the program director, providing guidance in putting into place the funding model.

The cash flow committee at DEWSC is the mechanism established to avoid the potential to think in the traditional manner about raising money in the university setting, specifically as it applies to funding, funding sources, and funding strategies. As Maxwell (1993) argues, our surroundings control our thinking and we quickly blend into the color of our surroundings. Similarities in thinking, mannerisms, priorities, talk and opinions are common within individual cultures. The stakeholders have an understanding of and comfort with the old system and a fear of the impact of any change. The committee members ensure that DEWSC stakeholders embrace change.

The committee is driven by the following principles:

1. Budgeting is a projection activity, not a “rear view”.

2. Benchmarking, awards, and incentives are critical for encouraging entrepreneurial achievement.

3. Discretionary funding and control are critical.

4. Strategic planning is critical to financial success.

5. Developing a business plan is central to success.

The Committee consists of the following individuals from industry:

1. Associate General Manager, Sal River Project

2. Vice President for Customer Service, Arizona Public Service

3. Vice President, Sundt Construction Company

4. Chief Financial officer, McCarthy Building Companies

5. Chief Executive Officer, Usher Insurance Surety

The School of Construction members include the Program Director, the Director of Strategic Relations and the Business Manager.

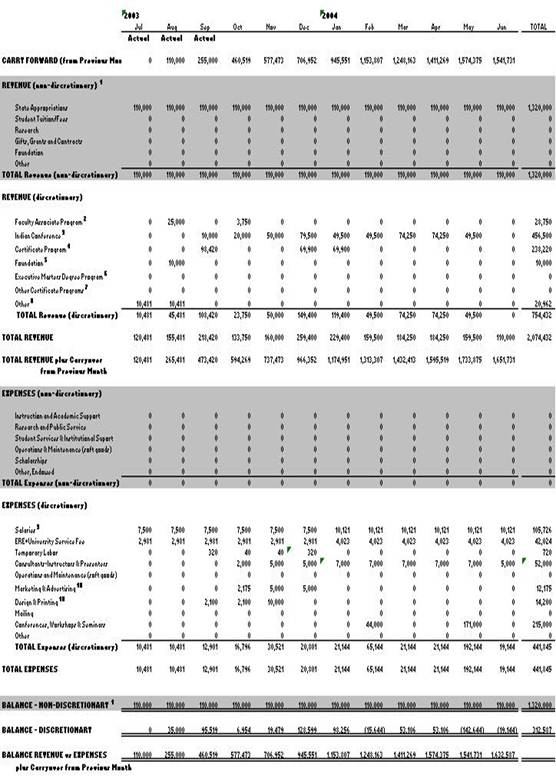

The objective of the cash flow committee is to help the School create a business plan, including income projections, to generate $1 million in funding, the net of which is for use at the director’s discretion. The vision is to provide funding that supports DEWSC’s strategic objectives, to identify new funding opportunities for the next five years, and to achieve the vision in a creative and dynamic environment. Figure 2 in Appendix B shows the income statement developed by the committee as the pro forma for revenue and expense projections, against which success is and will be measured. Current and projected discretionary funding vehicles over which the committee has provided guidance and direction are:

1. Faculty Associate Program (FAP). This program seeks $15,000 sponsorships from companies and individuals in return for recognition as sponsors of specific topics taught for credit at the School. Recognition includes naming the course and the syllabus after the company or individual, highlighting the sponsorship on the DEWSC website, an invitation to speak to the class at any time, or to provide a qualified instructor for the class.

2. Industry Advisory Council (IAC) dues income. Over 60 individuals pay $500 each, annually, to be a member of the IAC. They represent large and small companies, in all sectors of the construction industry (heavy civil, residential, commercial, etc.)

3. Alliance for Construction Excellence (ACE). Over 160 companies pay from $250 to $2,000 annually to participate in this continuing education and research incubation activity.

4. The Accelerated Master’s Degree program. Proposed to begin in Fall 2004, the net revenue from the fees generated by the program will provide significant discretionary funds to the program director.

5. Recognition Banquet. Although the annual Banquet, in its 16th year in 2003, is a breakeven proposition, it serves as a good will mechanism for the School and has tremendous corollary financial implications. Over 600 people attend the banquet with 60 tables sponsored by the industry, for the purpose of exposing high school students to the career options in construction. Sponsorships range from $250 to $1,500.

6. The Fluor Foundation annual gift. This $30,000 annual gift is to support staff work, the definition of which is determined each year.

7. The Ronald Rodgers annual gift. This cash donation of $35,000 annually by a DEWSC graduate, is dedicated to supporting staff working on internship placements, recruitment and retention.

Additionally, the following describes in more detail, two of the more prominent efforts to provide education and services to the industry, while raising substantial discretionary funds.

DEWSC Construction Management Certificate Program.

Using a program established by the Department of Construction Management at Colorado State University as a starting point, this program at the Del E. Webb School is described in the marketing material as targeting:

“…individuals who are currently in the industry and who need or want more formal construction management knowledge. The program is geared to the working professional and offered in the evening. Industry-related professionals who would benefit from the program include accountants and CPAs, attorneys, managers, insurance assessors, human resource and marketing professionals, property appraisers, realtors and developers, and lenders.”

Charging a fee of $3,495 for the 100-hour, non-credit program, the School enrolled 31 persons in the first session which began in September 2003. Because the program is non-credit, the entire revenue flow goes directly to the program. The net to the program director from the revenue stream was substantial, all of which was discretionary. A second session began in January 2004.

The Construction Management Certificate Program is an example of value-added service to the industry that also creates net cash flow for the program. Whereas industry is usually asked to donate funds, in this instance, a product is received in exchange for payment. The industry buyer receives a direct, tangible and valuable return on the investment. Similar certification programs in additional disciplines are being discussed as part of the School’s five-year business plan and discretionary revenue projections.

The American Indian Endowment for Construction Management Education

In October 2002 DEWSC teamed with the Advisor to the ASU President for American Indian Affairs to convene an Ad Hoc Committee for American Indian Education in Construction Management. The informal Ad Hoc Committee was established to address the fact that construction by tribal government owners has increased significantly in the United States. Largely based on new revenue streams resulting from gaming, estimated at $15 billion in 2003, tribes are building hospitals, schools and houses, and infrastructure construction is also increasing. Native American construction expertise at the policy level (tribal councils), administrative level and at the job site is seriously lacking. The largest grouping of tribes and Native Americans in the U.S. reside in Arizona and in adjoining states. One of the top construction management education programs in the country also resides in Arizona. The overriding question was: How is a great resource like DEWSC brought to bear on a critical need for quality construction in Indian country?

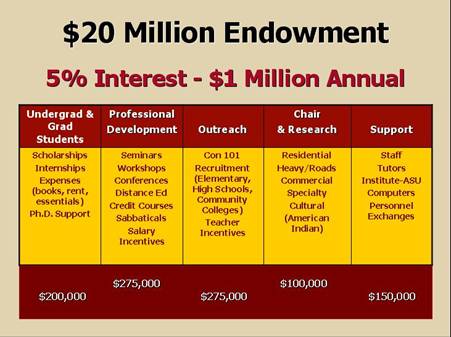

DEWSC presented a concept at the first committee meeting in October 2002, calling for tribes to establish a $20 million dollar endowment for American Indian Construction Management Education. The endowment would create a $1million/year revenue stream in perpetuity that would support, on an annual basis, such things as scholarships, community outreach, student recruitment, professional development and a Chair of American Indian Construction Education. The committee members supported the endowment concept and agreed to continue to meet. Figure 3 shows the original concept presented to the Ad Hoc Committee.

Figure 3: Endowment for American Indian Construction Management Education

In the second meeting in December 2002, the members agreed to support a national conference entitled “Construction in Indian Country,” income from which would be used to seed the endowment. This effort will bring together tribal officials, tribal construction personnel, non-Indian contractors, and federal, state and local agencies to begin discussing the issues of construction for American Indians, and begin establishing relationships. Based on sponsorships from non-Indian contractors of $10,000 each, and attendance of over 1,000 persons to the conference to be held in May 2004, it is anticipated that the revenue steam will provide a substantial net cash flow to seed the endowment and to provide discretionary funds to the program director.

This endeavor also provides added value to the industry, to Indian tribes and to Indian and non-Indian constructors. A service is provided, an endowment is seeded, people are educated and trained, a long-term asset is established to the benefit of all, and, the program director receives additional discretionary funds.

Discussion

Entrepreneurship in the university environment is not necessarily new. It has existed for many years among one cohort: the faculty. However, this particular type of profit pursuit is generally individual in nature, and does not have a direct monetary impact on the unit (department, division, college, etc.) – certainly not in providing a source of discretionary funds devoted to unit growth and enhanced quality. There seems to be a fine balance between faculty members consulting and being entrepreneurial in a private setting versus doing research and being entrepreneurial in the sponsored projects and university setting. Success such as has been experienced and described at DEWSC is not possible without concurrence of the faculty. Ultimately, the faculty must be a partner in the unit’s fund-raising activity, in one way or another and discussion must include this fine point.

If the university wins the hearts and minds of the faculty members and their perceptions are that they are being treated fairly by the university, then the research, licensing, and entrepreneurial activities will grow.

How then, does this correlate to fund-raising in general, and to raising discretionary funds in particular? At DEWSC faculty members have continued to do more research and less consulting over the past ten years. The authors believe this is a function of the director’s philosophy of giving faculty members wide latitude to thrive in a comfort zone that is academic. By nurturing the “revenue center and control” environment, where members see more return for their efforts by staying within the unit and their status as academicians is enhanced, the School has been able to refine and expand its fund-raising capacity. While building its research base, and keeping its asset (the faculty) close to home and leveraging it, DEWSC has been able to move more smoothly into non-traditional fund-raising, without disturbing, and in fact supporting faculty endeavors.

The attitude toward entrepreneurialism within the university has been changing and the challenge is one of how to facilitate acceptance and positive growth, and how to draw the productive faculty member into the fold, willing to be a revenue center within the scope of the unit, and still profit from his or her expertise. Experiences at the School of Construction indicate that entrepreneurship is nurtured when fairness, recognition, reward, and incentives are part of the process. It requires a plan and a well defined goal with specific objectives.

The authors believe the following comprise the elements that have contributed to the success of the School of Construction moving into a funding model that includes a significant discretionary funding mechanism. These actions have contributed to the overall environment in the department wherein individual initiative is encouraged, team work is the norm, and the individual members are supportive of one another.

1. Staff, faculty members, and programs are recognized and awarded for entrepreneurial initiatives.

2. Faculty members are encouraged, supported and rewarded for establishing revenue centers and are given control of and latitude in how their funds are used.

3. The Program director treats his department, to the extent possible in the system, as a revenue center and seeking discretionary funds is a department priority.

4. Successful faculty and managers are rewarded with control over discretionary funds.

5. Formulas to reward staff, faculty, and programs are developed to recognize individuals and programs that support the funding model.

Conclusion

The growth in discretionary funds at DEWSC to supplement endowment gifts has been an incremental process, achieved over a number of years. Lessons learned have been built upon and mistakes have certainly been made. Clearly, those lessons are invaluable and may be of interest and use to other construction programs in the country. This is not to say that other programs have not had the same experience or success, or that these are new nuggets. However, the research for this paper indicates that little has been written about fund raising in the construction discipline. It is the authors’ intention to provide a seed for discussion so that the entire discipline benefits. The following is a less than inclusive list of lessons learned on the road to discretionary funding that may sow the seed.

1. Program leaders need discretionary funds to run their program in the new academic environment.

2. Faculty members must be nurtured and rewarded during the fund-raising process.

3. Construction and construction management programs moving into formal fund-raising need significant industry support, including support to hire a developmental officer dedicated specifically to the program.

4. The development officer should have experience in business, construction, continuing education, leadership and management.

5. A significant amount of a program leader’s time has to be allocated to fund-raising.

6. Funding formulas will be influenced by who pays the salary of the staff and faculty involved and by who has assumed the greatest financial risk.

7. Programs such as the Construction Management Certificate program are money makers.

8. Fund-raising begins with the Alumni and spreads to the wider construction industry.

9. Creating an industry-led cash flow committee or task force greatly enhances the potential for generating new revenue-producing concepts and ideas.

Based on these lessons, recommended actions, from an academic and organizational perspective, include:

1. Establishing and coordinating a set of entrepreneurial principles for the program.

2. Adding entrepreneurial successes to the chairs’ or department heads’ evaluation criteria.

3. Collecting data on the successful entrepreneurs within the university and recognizing, rewarding and emulating them.

4. Changing the promotion and tenure procedures to include consideration of entrepreneurial success.

5. Recognizing and rewarding units with high percentage of staff and faculty on other than state-funded positions.

Some of these items come as no surprise to our colleagues in the business of construction education. Others may be new to them and useful in the context of specific program environments. In any event, we have learned that fund-raising has taken on a different perspective and that in order to survive financially, new ways of thinking, new approaches to seeking funds, and the ability to adapt to change quickly, are imperative.

References

John Maxwell, (1993) “The Winning Attitude,” Thomas Nelson Publishers.

Kozicki (2003) is an unpublished paper on ENTREPRENEURSHIP.

University of Nebraska Medical Center (2004). Peter Kiewit Foundation [WWW document]. URL http://www.unmc.edu/durham/donors/kiewit.htm

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2004). Industry at a Glance [WWW document]. URL http://www.bls.gov/

Appendix A

Figure 1: The Five-Year Endowed Professorship

Appendix B

Figure 2: Cash Flow Income Statement