(pressing HOME will start a new search)

The Provisions of Quality in United Kingdom Higher Education Institutions

Robert

D. Hodgkinson and David M. Jaggar

School

of The Built Environment

Liverpool

John Moores University

United

Kingdom

|

This

paper focuses on the measurement of the quality of education provision,

which is currently the subject of much controversy within United Kingdom

higher education institutions. It examines Government led initiatives

and the relative virtues of alternative approaches. The background,

which provides the impetus for the initiatives, is explored, and the two

main strands of quality audit and assessment arc distinguished. Drawing

from both authoritative sources and personal experience, the authors

target the quality assessment framework and procedures for particular

attention. Principles and processes are described and evaluated and a

comparative analysis undertaken of differing approaches to quality

provision in English, Welsh and Scottish university sectors. Future

proposals are examined, including profiling of department's courses and

commentary is made on both the cost and political implications of the

quality initiative. Finally a value added approach is advocated. Keywords:

Quality, Higher Education, Universities, United Kingdom, Assessment,

Construction |

Introduction

Prior

to the overt intervention in the affairs of higher education which emerged at

the beginning of this decade, United Kingdom higher education establishments

enjoyed a high degree of autonomy from state influence, despite the fact that

they were publicly funded organizations.

The

structural transformation evidenced in British universities, from a relatively

homogeneous system to one dominated by the drive for wider access, equity and

diversity, has been a central theme of higher education during the 1990's. The

climate for the delivery of a mass system of higher education was given

particular impetus by the extension of university status to the former

polytechnics, " an extension of elitist criteria to the non-elitist sector

of polytechnics and colleges". (6)

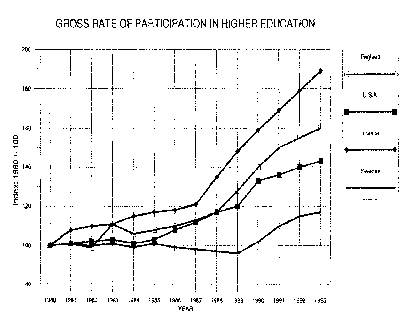

The

subsequent unprecedented growth in student numbers has led to great concern

being expressed by academics about the quality of education provision in United

Kingdom universities. Recently, there has been a retrenchment in the growth of

student numbers, matched by the implementation of stringent fiscal measures, and

compounded by a decline in both the level and distribution of the unit of

resource and student numbers. In 1995, universities are likely to be the

recipients of stringent Government financial cuts in the region of 3.5% per

student and a freeze on tuition fees and funded places (17). (Figure 1- Public

Expenditure on Higher Education and Figure 2- Gross Rate of Participation in

Higher Education.)

|

|

|

Figure

1. |

|

|

|

Figure

2. |

It

is against this backcloth that the former principles embodied in the quality

of education provision have been challenged and new initiatives implemented.

Quality in higher education is an international issue.

This

paper examines the role of central government through its agencies, in

developing new measures, systems and procedures for the enhancement of quality

in its universities in England, Wales and Scotland. In doing so, it draws upon

the writer's experiences as a quality assessor for Construction and Surveying

undergraduate degree courses in Scotland.

This

paper acknowledges the dual thrust of Government quality audit and assessment,

but seeks to place a particular focus on the latter, which has been the subject

of most speculation. Quality assessment has been and is the subject of

considerable change and controversy. Its implementation by Government agencies

has been seen as a radical departure, one whose approach is evolving rapidly.

The introduction of attempts to measure quality in the classroom, have

generated much debate in the national press and being increasingly viewed with

concern by those academics whose courses are being evaluated. Its implementation

has rocked the foundations of the academic establishment in the United Kingdom.

Background

For Change

The

Higher Education Quality Council (BEQC)(10) summarized both the genesis of and

reasons why quality assurance has been seen as a central concern of higher

education institutions. Until recently, higher education in the United Kingdom

has focused on the provision of forms of learning experience "delivered to

a well prepared minority", with claims for excellence being easy to

sustain. However, the unprecedented expansion in participation by students

from non-traditional backgrounds has led to increasing fears that the quality

of their education has been compromised and diminished. Particular attention

has been drawn to the stresses and strains occasioned by greatly increased

student numbers, more flexible learning strategies, credit based programs of

study, improved access and student choice. Within teaching programs, academic

coherence and integrity have been challenged, with some academics feeling that

the whole learning experience has been debased. As a consequence of the above,

the Government of the United Kingdom felt that the existing quality

arrangements for conventionally structured teaching programs, which had relied

on the policing role of the quasi-government agency, The Council for National

and Academic Awards (CNAA) (for polytechnics) and the monitoring activity of

external examiners, needed urgent redefinition to guarantee th4t student

experience would not suffer.

In

1992, the CNAA, expressed grave concern about the maintenance of quality

assurance standards, in the light of the growth in student numbers and the

diversity of new courses offered by many universities. Professional

institutions, in discharging their role as accreditors to many degree programs,

attempted to grapple with the implications of newly developed structures evolved

by many universities. These involved complex matrix structures requiring the

sharing of modules and greatly increased class sizes. As a response to the

above, the Government of the day enacted legislation which placed an obligation

on the Higher Education Funding Councils in England, Wales and Scotland, (HEFCE.,HEFCW

and SHEFC) to "secure that provision was made for assessing the quality of

education in institutions for whose activities it provides

(9). This duty was subsequently translated in to the assessment procedures

delineated later in this paper.

This

centralization of quality monitoring of education provision for universities,

controlled by central Government, contrasts markedly with the USA system, which

is largely independent of government and based on self-regulation and peer

review (13).

Quality

Audit and Assessment

There

are two main ways in which dominance of the quality provision in higher

education is exercised. In the first case, quality audit is conducted by the

Division of Quality Audit of the Higher Education Quality Council (HEQC). This

body (I 1) was established and is collectively funded by institutions of higher

education. Its specific focus is on auditing the processes by which institutions

control quality (4), and examining institutional mechanisms which are felt to

contribute to quality assurance. Such processes (10), involve the scrutiny of

"the design, monitoring and evaluation of courses and degree programs,

teaching, learning and communications methods, student assessment and degree

classification, academic staff, verification of feedback mechanisms etc."

The

second element, upon which this paper focuses, quality assessment is coordinated

by the respective Higher Education Funding Councils for England, Wales and

Scotland, who are responsible for deciding on the allocation of Government

funding to underpin higher education provision. Implicit in their remit is that

the assessment of teaching quality within university institutions, should inform

funding. Consequently they are obliged by Act of Parliament to ensure that

appropriate provision is made to assess quality in those institutions for which

they provide financial support.

In

seeking to discharge their remit, the funding councils have sought to promote a

framework for quality assessment based on utilizing trained academics, drawn

from parallel institutions and representing congruent cognate areas, who are

independent of the education institutions being evaluated. This provides for the

objective examination of the quality of education provision in individual

discipline/ cognate areas. Consequently institutions may be visited on a number

of occasions through the year. (In the United Kingdom, some of the larger

university faculties in the built environment, may encompass Building, Civil

Engineering, Architecture and Surveying degree programs, many sharing common

modules, with each cognate area being regarded as separate for quality

assessment purposes.) This process of quality assessment, envisages scrutiny of

both institutional and course-related documentation, student output, interviews

with both students, staff, former graduates and employers, direct observation of

teaching and supporting learning resources and facilities, a focus on the

output, i.e. pass rates, and employment of graduates etc.

Guiding

Principles

The

guiding principles of quality assessment as identified by the HEFCE(9) are to:

(i)

Ensure that all educational provision is of a satisfactory quality or better and

to provide a basis for the 'speedy rectification of unsatisfactory quality'

(ii)

Publicize assessment reports to encourage quality improvement

(iii) Link the funding of courses with excellence in education provision.

In

pursuing the above, quality assessment is seen as providing evidence to the

Government of the quality of provision for the range of subject areas offered by

those institutions, for which it provides funding. Furthermore, the outcomes of

such evaluations are meant to highlight the strengths and weaknesses in teaching

and learning provision within and between institutions. Publication of results

help disseminate good practice between institutions.

Process

of Assessment

In

essence the HEFCE approach to quality assessment comprises the following main

elements:

(i)

The submission by the institution under scrutiny, of a

self-assessment document.

This

is regarded as the most important element in helping external quality assessors

to form a view of quality. Until recently, analysis of self-assessment documents

determined whether or not an assessment visit was to be made to an institution.

Its analysis prior to a visit, allows key features to be identified for

evaluation and will consequently help to inform the structure of the visit by

assessors who will be searching for evidence to allow the substantiation or

otherwise of claims made for the subject area under examination.

(ii)

An examination of the self-assessment document by HEFC assessors, and its

comparison against a "template" of criteria.

The

template comprises six sections, which provide a structure against which

assessors evaluate the claims contained within each document.

(iii)

A decision on the quality of education as perceived from analysis of the above

document.

In

a number of cases, a visit by a team of suitably trained assessors, may take

place to confirm or discount a claim for excellence.

(iv)

The production of a quality assessment report by assessors, based on their

judgments of the quality of education provision displayed.

Such

reports are likely to cover such areas as student learning experience, depth of

achievement, congruency of individual subject aims and objectives. Each

assessment team will provide a rating within the report of either excellent,

satisfactory or unsatisfactory and indicate areas requiring action and

improvement.

(v)

A feedback report detailing evidence upon which assessors judgements have been

based.

(vi)

Publication of a quality assessment report for the department subject area.

Alternative

Approaches to Quality Assessment

Figure

5 (2), indicates some of the more important alternative approaches to quality

assessment pursued by individual funding councils for England, Wales and

Scotland, to the beginning of 1994. The major distinctions which reflected

pursuance of their own distinct policies, were:

|

|

|

Figure

5 |

(i)That

the self-assessment documentation, which each cognate area in England was

invited to submit, encouraged universities to make a claim for excellence. However,

this was extended in the Scottish system, and institutions were expected to rate

their self-assessment-documented submissions based on a four point scale, of

either excellent, highly satisfactory, satisfactory or unsatisfactory.

(ii)

That HEFCE's catchment of institutions and courses, being significantly larger

(some 150 universities and higher education institutions), elected to make about

four out of ten of its judgments on quality, based on an evaluation of the

self-assessment documentation provided by the institutions under scrutiny,

without visiting them. HEFCE used a "template" to analyze

self-assessment documentation provided by each programmed course, based on six

sections. This provided an objective basis for rating claims for excellence

and focused on:

a)

Aims and Curricula.

b)

Students: nature of intake, support systems and progression.

c)

The quality of teaching and students' achievements and progress.

d)

Staff and staff development.

e)

Resources.

f)

Academic management and quality control.

This

analysis of documentation sought to garner evidence to sustain a case for

awarding an excellent rating for quality education in the subject area being

reviewed.

(iii)

Three categories of judgment were used by both the Welsh and English funding

councils (9):

-

Excellent: "Education is of a generally very high quality."

-

Satisfactory: "This category will include many elements of good practice. Aims and objectives are being met and there is a good match between these, the teaching and learning process and the students' ability, experience, expectations and attainment."

-

Unsatisfactory: "Education is not of an acceptable quality. There are serious shortcomings which need to be addressed".

An

additional category is defined in the Scottish approach:

Highly

Satisfactory (16): "The quality of provision is satisfactory in all aspects

of the quality framework and, overall, strengths outweigh weaknesses."

Irrespective

of the number of categories used, some observers (2) were concerned about the

problems of making judgments on quality, because of the difficulties experienced

by assessors in providing consistency of treatment across and between

institutions and disciplines, given their often disparate missions and

characteristics. Judgment of quality on a three-point scale," requires

precise specification of the threshold criteria" (12) for both excellent

and unsatisfactory gradings. In addition, the majority of judgments are made

within the satisfactory banding, which encompasses a wide range of levels of

quality performance, which are undifferentiated.

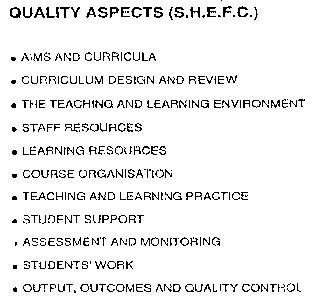

(iv)

The Scottish approach embodies an eleven aspect quality framework, which was

expanded for use by visiting quality assessors to sixty-three elements (Figure

3)(16). In practical use, it has been found to provide a very comprehensive

basis for assessment, albeit somewhat mechanistic. On the negative side, it can

make the process of assessment particularly time-consuming, given that evidence

has to be collected from either interview of staff and/or students and analysis

of documentation, including the self-assessment submission by the department,

within a very limited period of time (no more than three days).

|

|

|

Figure

3. |

Its

English counterpart offers a less well-defined approach, which appears markedly

reluctant to explicitly identify those aspects around which assessments are to

be made.

This

variance between the English and Scottish approaches has been the subject of

much debate, with the English system being conceived as unclear and confusing,

by both institutions and assessors. The latter, appeared to have been allowed to

develop diverse views as which aspects should be the subject of measurement and

what weighting if any, was to be accorded to each in seeking to form a judgment.

In some cases, it has been apparent that departments being the subject of

assessment, had failed to follow funding council guidance to present a case for

quality against their perceived aims and objectives. Some appeared to look for a

hidden agenda, producing self-assessment documentation whose focus was obscure.

Consequently the guidance provided by the English funding council, (which

appeared to favor a pragmatic non-prescriptive approach, leaving each individual

institution to present its own unique case, reflecting its size, mission,

complexity and diversity), is thought to need some clarification if it is to

present a more focused and structured user-friendly methodology which is both

coherent and understandable by all participants in the process.

(v)

Unlike the English and Welsh systems, the Scottish approach precludes the use of

an immediate oral feedback session to the academic team in the Institution

under scrutiny. In the former, at the end of the week following assessment, oral

feedback is provided by the assessment team, which may offer advice on key improvements.

The danger of such an approach is that it may stray away from discussion of

matters of factual accuracy, and be overshadowed by lecturing staff trying to

glean further information on how the assessment rating had been reached and

possibly the weighting or emphasis that assessors had applied to aspects of

assessment.

The

Scottish system takes a more guarded approach, being concerned with the need for

clear evidence to match decisions made by assessors. Written reports are

prepared by each of the assessors, and forwarded to a lead assessor for

compilation. A draft report is then prepared by the latter, approved by team

members, and a copy forwarded to the institution. The lead assessor then

undertakes to visit the institution to check on matters of factual accuracy

contained in the report. Consequent to this, the report is checked by SHEFC and

finally published. SHEFC are aware that negative reports could be the subject of

a challenge in a court of law, and require the feedback process to be the

subject of careful and thorough screening.

An

indication of the seriousness with which departments sub cut to scrutiny are

prepared go, was highlighted during a recent assessment visit. Every member of

staff questioned by assessors was given a form by their institution upon which

to record the questions asked of them and their responses. This information was

fed back to the center and a dossier compiled, which in the event of a

disagreement on the outcome of the visit, could be used in a court of law to

mount a challenge to the judgments reached by the assessors. Each system has its

merits, the Scottish system provides a more rigorous, if circumspect approach,

whilst the English variant meets the needs of the institutions for immediate

feedback.

(vi)

Both Welsh and Scottish approaches to quality assessment, use the results to

inform funding and reward excellence. In the Scottish system, subject areas

awarded an excellent rating maybe rewarded with a 5% increase in income, based

on the finding received for the tuition fees for each fall-time student

equivalent.

(vii)The

English approach appears to place greater emphasis on observation of teaching

by assessors and encourages the latter to give feedback and a rating of

lecturers' performance. Consequently there is a likelihood that the

preoccupation with teaching can lead to it being given a higher weighting by

assessors, than other elements of the quality framework. A recent review of

assessment of the quality of higher education by Barnett(2), recommended that

"Classroom observations should be limited to a sample sufficient to test

the department's claims in its self-assessment'. The Scottish system provides

for teaching evaluation adjust one of eleven aspects (Figure 4), within the

aspect "Teaching and Learning Practice", breaking down its assessment

into six elements, for evaluation purposes. Consequently the approach neither

encourages or discourages weighting of this aspect of the quality framework.

However, since the eleven aspects comprise sixty three elements, each of which

need to be addressed, there is only sufficient time during an assessment visit

to an institution to allow a limited snapshot of teaching observation, and this

is not likely to be representative.

New

Initiatives in Quality Assessment

Quality

Assessment Framework

Plans

have been revealed both to change the existing HEFC quality assessment framework

of aspects, and to implement a new assessment grading format (15). The proposal

is for the introduction of a framework for quality assessment based on the

following six core quality aspects:

a)

Curriculum design, content and organization,

b)

Teaching, learning and assessment.

c)

Student progression and achievement

d)

Student support and guidance.

e)

Learning resources,

f)

Quality Assurance Enhancement.

Assessors

will be expected to visit cognate areas and grade each aspect on a scale of one

to four, where one is regarded as the lowest rating. Departments will be judged

adequate as long as they do not receive a one rating against any of the six core

aspects. Inadequate departments, will be judged to be "on probation"

and expected to remedy their perceived shortcomings by the time of the next

visit, some twelve months later. Failure after this would be likely to lead to

withdrawal of funding for the course.

Profiling

An

alternative approach to the above, has been proposed by BEFCW(12), based on

profiling. This would allow for the judgments made by assessors to be based on

their assessment of the relative strengths and weaknesses of the quality

provision within a subject area. Such a profiling approach, by representing the

education provision on a continuum, would be expected to provide a more apposite

description of the perceived provision being assessed. Figure 5, represents this

balance of Judgment of strengths and weaknesses. It shows six key aspects of the

education provision against which judgment is to be exercised. The proposal is

that sets of "quality statements" would be determined for each

dimension, such that they represent what is perceived as constituting excellent

and unsatisfactory quality for each of the aspects, i.e. the extremes of good

and bad practice. These would act as a benchmark against which the level of

strengths and weaknesses for each aspect could be identified. Consequently,

education provision would be judged as unsatisfactory, where the profile

indicated "significant weaknesses in some dimensions which were not

outweighed by strengths in others. Excellence would be evidenced by a profile

indicating good practice across each aspect."

|

|

|

Figure

5. |

Profiling

could also be used by departments when writing their own self-assessment

documentation submissions, prior to a visit from the external quality assessors.

Problems

One

of the problems of operating in accord with the above practice is that each of

the six aspects has a number of constituent elements. For example if teaching

and learning practice were one of the chosen aspects, it could contain up to six

subsidiary elements, against which assessors would seek evidence upon which to

make a judgment. Decisions would then have to be made as to whether or not a

weighting should applied for each element constituting an aspect of the

education provision.

Benefits

A

number of advantages are claimed for this approach, including that profiling

would provide a much better basis for subsequent discussion and feedback between

assessors, institutions and staff being evaluated. Furthermore, it could be seen

as better reflecting the complexities inherent in judging the relationships of

those aspects impacting upon education provision. It is also felt that the

profiling approach would lend itself more readily to addressing the wide

spectrum of courses/subject areas being evaluated by assessors. Consequently, it

would forma much better basis for quality improvement within and between

institutions.

Cost,

Accreditation and Politics

Cost

A

senior academic (18), has questioned the efficacy and cost of the government led

initiatives in both audit and assessment of quality in higher education.

According to Barnett (2), the cost of assessment alone is running in the region

of 1/2% of the annual budget for the teaching function. John Bull, Vice

Chancellor of Plymouth University, has pointed to the diversion of scarce

resources from teaching to the assessment of quality function, which he sees as

"hampering the very activities,$ it was designed to assess". He

indicated that a recent decision to extend assessors' visits to every cognate

area in England, within a five year cycle, would be both a retrograde step and

counterproductive, since greater numbers of assessments would mean that

significantly more university staff would be needed to undertake the role of

assessors. It has been estimated (7), that each institution would have to

provide the equivalent of two full-time members of staff per year per cognate

area. However, it has been indicated that pace of progressing the added volume

of activity could founder beyond September 1996, since there could be no

certainty that sufficient government funds would be made available.

Financial

Reward for Excellence

The

intentions of the Government to "inform funding" and thereby reward

excellent teaching activity at the expense of penalising those universities with

least resources, has been seen by Griffith(8), as compounding the gross

inequalities that already exist between institutions. The counter-argument being

that additional investment should be provided in those areas performing less

well, to make them more capable of improving their quality standards to level

equivalent with the more advantaged university departments. The fear is

expressed that such a formula-driven approach to financing teaching, is likely

to lead to even stricter monitoring of academic staffs teaching activities and

"... collegiality will give way to individual accountability", with

concomitant performance indicators and performance-related pay.

Certification

to an Externally Accredited Standard of Quality

A future scenario could be envisaged in which institutions were required to apply for certification of their quality management systems by an independent non-governmental accrediting body, to an internationally recognized standard,(I) e.g. British Standard 5750, (equivalent to ISO 9000). Such standards are based on frameworks, which allow the parent organization to interpret criteria for assessment based upon their own perceived organizational needs. At least one university, Wolverhampton (7) has followed this path of certification by an independent "policing" organization. Such a process, however would most likely be confined to certifying the institution's and department's systems and procedures, being more akin to quality audit. Such an approach would be subject to the same criticisms leveled at similar certification quality standards applied to industry and commerce in the United Kingdom. Such criticisms focus on both the cost of the certification process and its maintenance together with the proliferation of bureaucratic processes, which often result. Certification to comply with the British Standard says little about the quality of the product, but more about the confidence of the consumer that the process will minimize mistakes and errors. Such an approach guarantees the system but not the quality of the end product, namely the provision of a quality educational experience for students.

Experience

has indicated that once certified, it is difficult to maintain the enthusiasm

and commitment of staff. Furthermore, certification is specific to the

organization, being assessed against standard criteria, which have been

interpreted from the British Standard, making it almost impossible to benchmark

one organization against another. Notwithstanding this, some believe that by

pursuing such a course of action towards quality management, it can be

considered a first step in the road to total quality which entails an

organization-wide commitment to a customer orientated quality approach similar

to that propounded by Oregon State University (3).

A

Change of Political Party

Davis

(5), the Labour opposition spokesman on higher education, has indicated that,

were a Labour Government returned to power at the next general election, it

would give serious consideration to the installation of a unified agency for

quality, rather than the dual system presently operating, separating quality

audit from quality assessment. Such a national agency could work more closely in

partnership with institutions in both the selection and development of the

assessment process. Even a regional framework for assessment is being

considered.

Conclusion

Irrespective

of which of the above assessment methodologies are used, one major issue

remains, to identify a system of assessment which is fair for all universities.

Assessors are presently faced with making judgments of university departments'

education provisions, which are significantly affected by which mission

statements are being pursued. Consequently in examining different university

departments in the same cognate area, one may be evaluating a mass provider, for

which the emphasis focuses on wider access, flexible learning patterns and

encompasses a credit accumulation and transfer scheme, with a university

department which pursues elitist access policies, limits intake and provides a

very traditional structure for learning. The former often suffers badly, when

national league tables comparing universities are published. Some of the newer

universities have been calling for assessment methodologies which take

cognizance of "value added criteria" (14), based on the measurement

and comparison of entry and exit qualifications and student achievements.

Such

an approach, could redress the balance somewhat. The "comparative

method" of calculating value added, provides a means of indicating

"how well a course is doing-in terms of its student achievements-compared

with similar courses with similar intakes". In addition, it is said to take

account of known differences in degree classifications between subjects, wide

differences in entry qualifications, and indicate how relatively better or worse

the course's degree results are by comparison with predictions based on national

data. In the highly politically charged atmosphere which exists in university

higher education in the United Kingdom dominated by a wide variety of different

factions, it is one thing to identify a fair system and another to convince all

parties that it should be implemented.

There

is considerable international evidence that points to the robustness of the

United Kingdom system of higher education and the fact that it is

"operating at a generally high level of quality"(2), with little

diminution in its reputation for a quality product. Consequently, some view the

Government's focus on quality in higher educations ill conceived and heavy

handed, based on a lack of confidence that the sector could possibly absorb the

multitude of changes that have taken place, without some compromise in quality.

Nevertheless, assessment will certainly provide more tangible evidence of the

quality of provisions. Since the Government is determined to pursue the

policies, success may eventually be determined by the “quality” of the

quality assessment procedures.

References

BSI.,

British Standard 5750; 1987 Quality Systems, British Standard institution,

London, 1987.

Barnett

R. Parry G et al., Assessment of the Quality of Higher education, Center for

Higher Education Studies, Institute of Education, University of London, April

1994.

Coate

E.L., TQM at Oregon State University, Journal for Quality and participation, Dec

1990, pp90-101.