|

(pressing HOME will start a new search)

|

|

Industry Practice and Legal Problems

Wilson

C. Barnes and Jose D. Mitrani

Construction

management Florida

International University Miami, Florida |

David

J. Valdini

Leiby,

Ferencik, Libanoff & Brandt Plantation,

Florida |

|

This paper reports on the third study in a series devoted to identification and examination of practices in the construction industry that lead, directly or indirectly, to conflict and ultimately to legal entanglement. The study looks at the state of Florida and probes conduct of both general and sub contractors in all regions of the state. Response data is discussed and placed in context with findings of the other studies in the series. Causal factors of litigious generative conduct are rated as are resolution forms for common claim/ dispute categories. Prevention through education is fostered and conduct of subs is noted as different from that of generals in some instances. Keywords: Construction Practice, Pitfalls, Preventive Training, Law. |

Introduction

Background

and Objectives Work was conducted on three separate but related research

projects, funded sequentially, and directed toward improvement of knowledge

surrounding the high incidence of law suits and lesser levels of adversarial

conduct in the construction industry.

The

work was initiated in 1990 at the recent height of outrage over high levels of

litigation in construction; levels which had caused many operatives to suffer

damaging losses, shift to new manners of organizing for business such as

partnering, or leave the industry entirely. The impact of litigation on the

industry was all too apparent and "old fixes" such as ADR and

partnering were clothed anew and readily prescribed by the highest councils as

measures to promote relief. Relief attributable to these techniques and to

accompanying attitudes of cooperation has indeed begun to appear.

However,

a nagging concern hangs over the industry that we have a long way to go before

the whole matter of adversarial conduct is being met as effectively as

possible. It is just this concern and its related issues that the work

associated with the three projects attempted to address. While it is

relatively easy to catalog the legal transgressions and their consequences, it

is much more difficult, and quite possibly more important, to define and

counter the causal factors underlying the practices of business that lead to

difficulties with legal implications.

The

three studies examined profiles of practice and the related causes of problems

rather than attempting to fix blame or list legal winners and losers. The

study conduct, spanning four years, reflects change in industry conditions and

attitudes as well as in contractors' perception of self weakness.

The

research sought to identify those problems of frequent occurrence and

consequence to controversy, and search for features of business conduct that

directly or indirectly had the potential to promote or preclude the problems.

The cumulative data provides a unique base of thought provoking information on

the business of construction. It was sponsored by the State of Florida

Building Construction Industry Advisory Committee.

Investigation

Development

At the outset of inquiry, the Phase I study set up abroad-based exploration of

practices in the industry that were linked to later legal difficulties. A

conventional literature search and review of court records produced minimal

hard fact to influence our opinions or define direction. "However, the

results in terms of inferential data, i.e. textual allusion or suggestion as

to causal activity or lack of activity were remarkably consistent in

highlighting proper procedure as a primary issue to be examined more

closely," (Barnes, Mitrani & Valdini 1994). This theme was reinforced

through extensive interviews with contractors, subcontractors, design

professionals, and construction attorneys. Weak and poorly conducted

management was spoken of consistently as the leading contributor to trouble.

Several

years previously, Ellison and Perreault had cited contract and management

administration issues as causes of litigation that occurred most frequently

and called them the areas of practice most needing improvement (1988). This

corroboration was identified by the Florida team after Phase I work,

ironically reinforcing the independent validity of both conclusions.

The

development of theme in Phase I led to a questionnaire type survey eliciting

multi-dimensional information from 413 South Florida contractors. A discussion

of this survey and its findings have been published previously and will

substantiate the interview revealed central theme of practitioner failure to

tend to business (Barnes et al, op city. Repeatedly, it was clear that both

administrative and technical aspects of management were receiving inadequate

attention. Loss of control was the frequent outcome at all levels: activity,

project, and company.

Phase

II studies extended and expanded the previous work to include a more specific

survey addressed to a wider audience. The data from that effort reinforced the

findings of the initial work. The general contractors in a still predominantly

regional audience responded more readily than did the subcontractors during a

period of deep recession in the industry. Despite high correlation with

previous response distributions, the total numbers lacked validity as

substantive evidence. That phase of work also focused on the generation of

seminar type education modules in identified areas of practitioner weakness

for presentation to industry groups (1992).

A

final round of survey was carried out under Phase III of the total effort.

This survey was evenly distributed state-wide to a grand total of 1074

construction firms and is the primary subject of discussion in this paper.

Survey

Currency The third survey was designed to increase and improve the data base

developed in the first and second studies. It continued, through organized

sets of questions, to address specific issues of conduct identified in the

Phase I work. The questions addressed basic features of project related

activities identified as causing disputes leading to litigation and the nature

of resulting economic impact; and, typical categories of claims or disputes

with information on form of resolution used.

The

survey form required time and thought for proper completion. It incorporated

several matrix questions seeking specific answers that depended on recall or

research for accuracy. The issues that these questions addressed are extremely

complex in themselves and reflect the basic operational problems in our

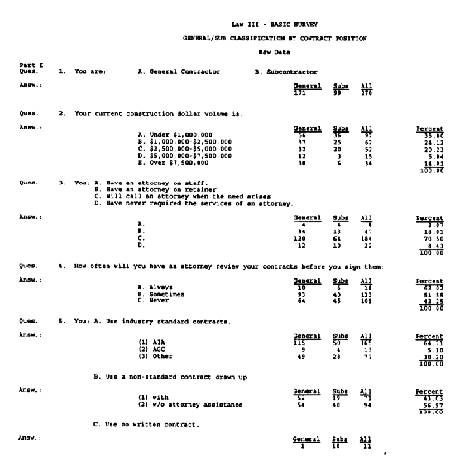

industry. Raw data from the third survey is presented in Tables 1. through 8.

and reflects the questionnaire format and content. A blind indexing was used

to distinguish generals from subs and the three trade breakdown of those

selected sub categories. Additionally, we were able to track responses from

four geographical areas and three code jurisdictions in the state. While a

full analysis of these geographical and code breakdowns is beyond the scope of

this paper, the gross data showed distinct patterns of conduct and response.

A

random selection of contractors was made throughout the State of Florida in

rough distribution to that of the general population. All were contacted

initially by telephone to elicit cooperation. Of 465 mailings to general

contractors, 124 responses were received. In addition there were 24 personal

interviews of generals bringing the total to 148 responses. Of 619 mailings to

Air Conditioning, Roofing, and Electrical subcontractors, 122 responses were

received for an overall combined rate of 24%. Of the 122 responses from the

trade classified subs, 23 indicated they were generals. This is understandable

since some traditional subs work primarily or exclusively as main or prime

contractors rather than through a general. We felt the number of these was

significant and therefore we shifted their classification from sub to general

for a raw data summary reflecting contract position. We then showed responses

from 171 generals and 99 subs.

The

lower response rate of subcontractors reflected our experience in the earlier

surveys. The breakdown of responses does exhibit some interesting differences

between generals and subs. These can be seen in the raw data information

included herein in the Tables 1-8. We show raw data reflecting responder

classification by contract position, i.e., main or subordinate. As most in the

industry realize, contract position has serious implications in terms of

access to the client's money as well as obligation and responsibility for what

happens on the job site. We also compiled the data as a function of

trade/tradition, i.e., how a company is classified in the traditional sense.

Our data presented here however, reflects how firms work rather than what they

are called. This is reversed from the presentation in the technical report for

the project (Barnes & Mitrani, 1994). Either way, there are differences

which might be of consequence in the pitting of subs against generals, but

these are not emphasized in this discussion.

It

is of continuing interest however that responses from generals in all study

phases reflect a greater attempt than that evident on the part of subs to

answer questions accurately and to provide constructive comment. We have

speculated on reasons for this in the previous studies as perhaps being

attributable to stronger business positions of the generals over the subs, or

larger picture views of the generals, or the possibly more detached

organizational role; of the general type responders. We simply don't know, an(

the mystery is still there. In fact, it is deepened by the diversity of

subcontractor trades and their traditions of conduct.

Discussion

of Questions The survey questions elicit information in four different areas.

The first area treats identification and classification of the responder by

business volume, and the nature of responder firm relationships with

attorneys. This was general information gathering, intended to be relaxing to

the responder and useful to highlight any relation of size or legal support to

the overall incidence of problems.

All

responders did not answer all questions on the questionnaire, some were

extremely precise in answering, and some were less so. Also, the matrix cells

in the question areas of Parts II & III contain numbers of instances

reported, not the number of contractors reporting instances. Therefore, some

cells contain numbers exceeding the number of individual firm responses to the

related questions on the questionnaires.

|

|

|

|

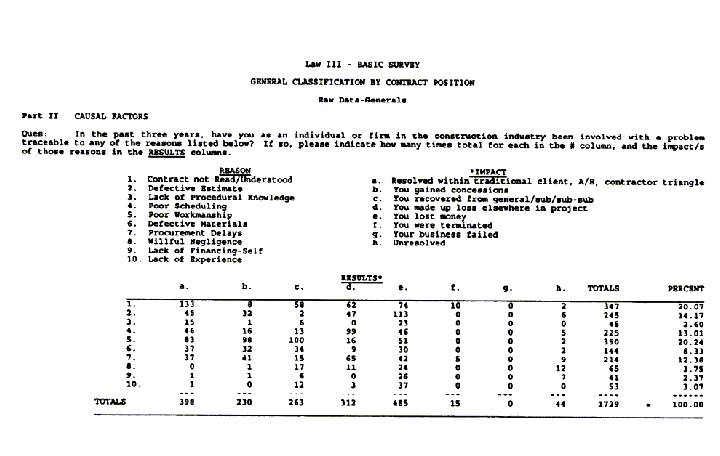

Table

1. |

|

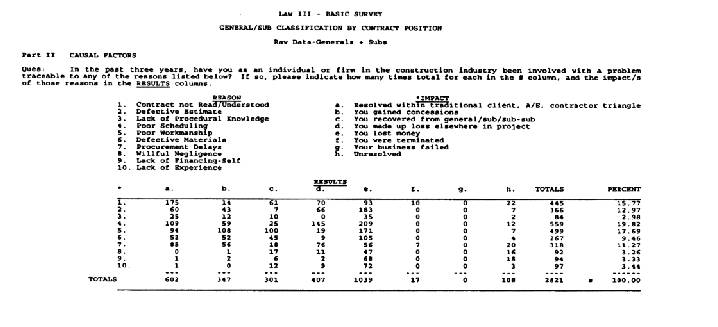

The

second area addresses the causal factors a firm felt problems they had

experienced were traceable to. Ten reasons and eight choices of results gave

responders opportunity to express their known or suspected underlying causes

of problems or non-optimized opportunity. Poor scheduling lead the list of

perceived reasons for having a problem. Defective workmanship and Contract not

read or understood also were identified as prominent reasons. Defective

estimate rounded out the top four. The orthogonal listings in this matrix,

which can be seen in the raw data sheets of all Figures, dealt with the

results experienced for various reasons chosen. You lost money was the

overwhelming result selected. Resolution with in the traditional contractor

owner-designer triangle, Making up the loss elsewhere, and Gained concessions

were also frequent choices.

The

absolute numbers recorded from the responses are less important than the

pattern of conduct they represent. From phase to phase these numbers have

varied somewhat but the general picture hasn't changed. For example,

previously, defective workmanship was clearly the leading reason; but poor

scheduling was a strong second. Now, from a different audience at a different

time, there is a shifting of emphasis. In reality, we are looking at the same

phenomenon, five or six dominant reasons that are not excusable, and the rest

that are highly undesirable as conduct. The issue of poor scheduling is spoken

to in greater detail later.

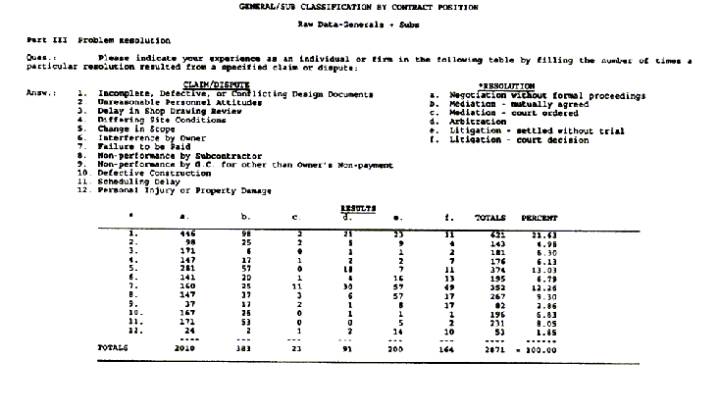

The

third area of inquiry on the survey addressed the resolution of problems.

Another matrix of choices ranked problems that typically are bases for claims

or disputes against legal forms of resolution. Looking beyond the leading

choice of problem, i.e. Incomplete, defective or conflicting design documents,

we note that Change in scope and Failure to be paid are next in frequency of

occurrence. For resolution, the overwhelming indicated mode is Negotiation

without formal proceedings. This would seem to indicate merit in dealing with

a problem at the earliest possible time by the most appropriate people. Such

resolution's early position in the escalating ladder of formality makes it a

natural choice for cost effective reasons alone.

|

|

|

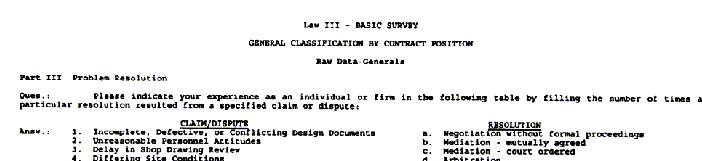

Table

2. |

|

|

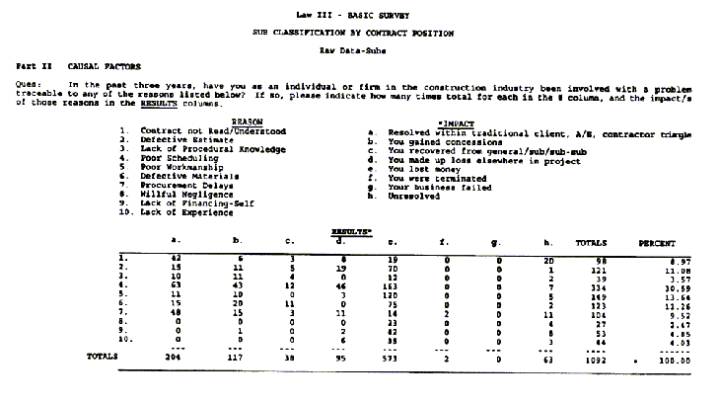

|

Table

3. |

|

|

|

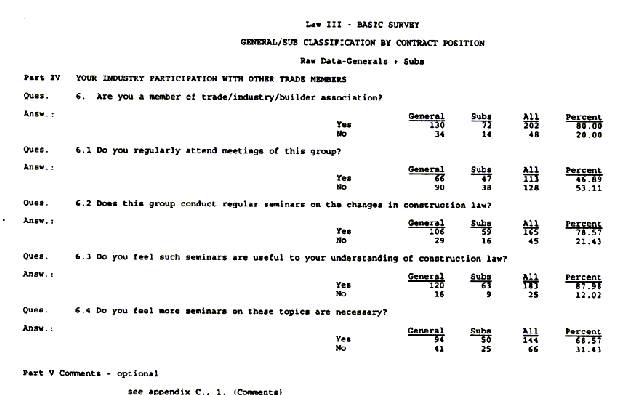

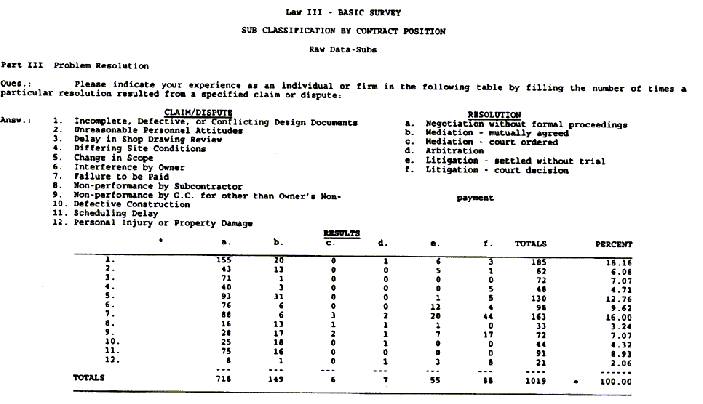

Table

4. |

A

fourth area of inquiry sought to develop an understanding of how contractors

regard participation in trade or industry associations. This subject was

brought into a survey for the first time here.

Survey

Analysis The third phase survey of interest focused on the causal factors

which contractors perceive to be responsible for problems in the industry. It

also explored usage of the types of resolution that are at work in the

construction industry to address these problems. Overall, the responses of the

generals and subs as two distinct groups were similar in a gross sense but

markedly not similar in detail. To understand the preceding statement, we have

to look at the relative ranking of the matrix answers as well as the ratios of

response to the simpler format questions in Part I (the first area referred to

above).

|

|

|

Table

5. |

|

|

|

Table

6. |

|

|

|

Table

7. |

|

|

|

Table

8. |

Part 1- General Information

Question 1. In the analysis by contract position which we have selected as of greater import to our presentation, the sub responders represent 35% of the total. This reflects the shift of 23 traditional sub addressees to the general classification which they responded under. Although that selection of analysis reduces the apparent number of subs, we believe it to be a more accurate representation of how they work and what procedural pressures they are subject to. This percentage should be borne in mind as we proceed through the listed questions.

Question 2. Roughly a third of both generals and subs who responded had a current construction dollar volume of less than one million dollars. As the categories of volume increased in value, the share of total enjoyed by the two categories stayed close with the subs gradually reporting less than generals as a percent of the total.

Question 3. Both generals and subs indicated a strong preference to call an attorney only when the need arises. Comparatively few of both said they have never required the services of an attorney, and fewer firms yet said they had an attorney on staff.

Question 4. Responses to this question reflected a mixed attitude about attorney review of contracts. While roughly a third of the generals said they never used an attorney for review, half of the sub responses showed that same independent mode of action. Just under ten percent of the responses indicated attorney involvement all of the time.

Question 5. About 38% of the contract type responses indicated usage of the AIA form with another 20% reflecting AGC or some other standard form. Another 38% indicated usage of non-standard contracts and, surprisingly, 43% of those were reported as being drawn up without attorney assistance. As a percentage within their classification, subs went without attorney assistance by a margin of two to one whereas generals were evenly split on these nonstandard forms. Many attorneys feel the industry would be better off to employ them in a preventive advisory role rather than the much more expensive and disruptive role of subsequent conflict. As far as no contract at all, less than 3 °/a of responses indicated that mode but again, subs by ten to one chose the riskier course.

Part

II -- Causal Factors.

In

the causal factor matrix of reasons and results, responders had a large number

of choices. Quite apart from distribution, the spread of answers suggests that

the reality of experience is consistent with the listed categories excepting

business failed as a result. As with the previous Phase II survey, reasons

1,2,4,5,6 & 7 garnered the lions share of responses. However, the ranking of

both the combined and the sub responses for these numbered reasons is quite

different in that here poor scheduling is clearly the reason of first choice by

large numbers. This is in contrast to the responses for generals which reflected

Phase 11 by citing poor workmanship as the most troublesome reason. An

interesting point now can be raised as to whether those firms in a subcontract

position are deficient in scheduling skills or simply more subject to agenda

pressure from the general. Also, it seems appropriate to note that generals find

poor workmanship very troubling where as the subs find it less so. Does this

mean that the generals consider work of the subs to be poor or work of their own

in house trades to be lacking? Also we must remember that the survey only

presented query to air conditioning, electrical and roofing subs. There is a

whole range of other independent subs and specialty contractors that the

generals could be referring to or indeed to their experience on the whole.

Contract not read or understood remains in a strong third position throughout

while defective estimate is not far behind. Procurement delays are more

significant to generals, while defective materials are more significant to subs.

In

terms of results, you lost money is everybody's favorite. This is followed by

resolution within the traditional triangle and then flip flop between the

generals and subs on the issues of making up losses, recovery and gaining

concessions. It is interesting to note that the subs rank gained concessions

higher than generals do. No responders indicated business failed, and only a few

generals noted terminations.

Part

III -- Problem Resolutions.

A

matrix of choices is used again to provide response opportunity for indicating

how various claims or disputes were resolved. There is little consistency in the

ranking o claim or dispute incidents between the generals and subs. It is clear

from the raw data that generals are troubled more by poor design documentation

than subs are. Documents used by the subs are generally prepared by engineers

while those

used

by the generals are usually prepared or coordinated by architects. Subs on the

other hand note getting paid as their leading cause of claims or dispute while

for generals it is fourth down the line. Both generals and subs are bothered by

change in scope, and whereas generals experience frequent disputes over

non-performance by subs, the subs cite interference by owner as their next

frequent grief.

The

primary indicated method of settling disputes is negotiation. Both generals and

subs overwhelmingly said that their experience was to resolve problems by

negotiation rather than any other method of formal or informal dispute

resolution technique. Mutually agreed mediation was also used, but to a much

lesser degree, while court ordered mediation or arbitration was rarely or never

used. Where litigation did play a role, less than half of those ending up in

litigation were settled by trial. In general, these results are consistent with

those of the earlier survey in Phase II.

Part

IV - Your Industry Participation With Other Trade Members.

This

survey, third in the coordinated series, included a section on participation in

trade or industry associations. While these groups are very popular among the

respondents, according to the survey, subs were more likely than generals to be

active members.

Question 6.0. By four or five to one, both generals and subs, are members of a trade/industry/builder association with subs enjoying a modest percentage edge in participation.

Question

6.1. Subs are also more likely than

generals to attend meetings regularly. Perhaps this is a function of common

training, licensing, socializing, whatever we don't know; but it does reflect a

pattern of sub cohesiveness we observe in other areas.

Question

6.2. Both groups of subs and

generals indicated that regular seminars on changes in construction law are

conducted by the associations they belong to.

Question

6.3. 88% of the responders

indicated that such seminars are useful to their understanding of construction

law. This was a uniform feeling in both groups.

Question

6.4. A little more than two thirds

overall thought that more seminars on these topics were necessary. Slightly more

generals than subs felt this way.

Conclusion

The

data discussed in this paper is part of a body accumulated over four years of

investigation into practices in the construction industry that lead to legal

difficulties. This third body of data is the largest to date drawn from an

increasingly wide geographic population. The profiles of responses from general

contractors are strikingly similar over the three surveys. The profiles of sub

contractors, only now beginning to emerge in useful numbers, are similar to

those of the generals in a gross sense but markedly different in detail. It is

just these details of performance or perception of performance that may lead us

to a better awareness of our internal differences and through this to better

understanding. Many contractors are aware of these problems and causes but see

improvement outside their control. For example the poor scheduling of mechanical

work and an overall perception of poor workmanship.

These

investigations have led to the development of five seminar modules for

continuing education use in the industry. The modules address key practice areas

of contracts, scheduling, construction liens, bonds & insurance, and cost

accounting. More knowledgeable contractors are more likely to observe good

business practice, and reduce their exposure to or be better prepared for

conflict.

References

Barnes,

W.C., Mitrani, J.M. & Valdini, D.J., "Dispute Avoidance for Small and

Medium Contractors," Proceedings of Dispute Avoidance and Resolution in the

Construction Industry, UMIST & University of Kentucky, October, 1994.

Barnes,

W. C., Mitrani, J.M. & Valdini, D.J., "Practices and Pitfalls in the

Construction Industry That Lead To Lawsuits," Proceedings of the 30th

Annual Conference, Associated Schools of Construction, Peoria, April 1994,

270280.

Barnes,

W.C. & Mitrani, J.M., "Practices in the Construction Industry Which Are

Subject to Lawsuits - Phase Two," State of Florida BCIAC, FIU Department of

Construction Management Technical Report No. 108, 1992.

Barnes,

W.C. & Mitrani, J.M., "Practices in the Construction Industry That Lead

To Legal Problems - Phase Three," State of Florida BCIAC, FIU Department of

Construction Management Technical Publication No. 114, 1994.

Ellison,

W. & Perreault, R., "Liability Problems Which Result in

Litigation," The American Professional Constructor, Vol 12 No 2, 1988, 6-9.