(pressing HOME will start a new search)

- ASC Proceedings of the 27th Annual Conference

- Brigham Young University-Provo, Utah

- April 18-20, 1991 pp 65-70

|

(pressing HOME will start a new search)

|

|

COMPETENCIES

FOR CONSTRUCTORS: AN ALTERNATIVE APPROACH TO CURRICULUM DEVELOPMENT

|

| The

criteria and standards used to evaluate Construction curricula have been

discussed and debated for several years, particularly with regard to the

accreditation process. The current standards being utilized by the

American Council for Construction Education (ACCE) distribute courses

into five categories, establishing a minimum number of credit hours for

each. These delineations can become rather arbitrary, producing either a

distorted or incomplete assessment of a program's curriculum and course

content. As

members of the University of Washington's Building Construction

Curriculum Committee, we are currently developing an alternative

methodology for review of curriculum and course content. A matrix of

proposed competency areas for our construction graduates has been

completed, and statements are now being formulated for each area.

Following a review by industry and alumni representatives, these will be

used to evaluate the current course offerings to assure that all

competencies are being addressed. This

paper chronicles the progress made to date. In addition, it sets out the

parameters to be followed in completing what has turned out to be a

rather significant undertaking. |

INTRODUCTION

Faculty,

administrators, and accrediting bodies all grapple with the common question of

how to evaluate curricula of degree programs. In most cases, this is

accomplished by a set of criteria and standards developed either by the program

itself or an accreditation board.

Once established, it is fairly common for review criteria to be treated

as though they were cast in stone, with little consideration being given to

their review and modification.

On

of the goals listed in the ACCE's Standards and Criteria for Baccalaureate

Programs/Form 103 is to "review at regular intervals the criteria and

standards which ACCE has adopted to evaluate programs in construction

education." This is in line with the objective expressed in the Associated

Schools of Construction's Bylaws to "innovate, improve, and adjust

curricula, educational and teaching processes, and instructional materials to

meet changing conditions."

The

purpose of this paper is to describe an alternative evaluation method to that

currently used by ACCE in the accreditation process. It is currently in the

formative stages, and therefore will require additional review and refinement.

Via this process, the Department has embarked on the most comprehensive

evaluation of curriculum and course content that has been attempted in its

twenty-seven year history. This paper describes the methodology we are

following, and gives an example of the competency statements being developed.

This evaluation method should be given consideration by the ACCE for

incorporation into the accreditation criteria and standards for Construction

programs.

BACKGROUND

The

quantitative approach to curriculum evaluation is based on the assumption that

if a sufficient number of courses are taken by a student in designated areas of

study, the student will have obtained (or at least have been exposed to) the

knowledge necessary to obtain his/her degree. While this is a fairly common

approach utilized by accreditors and administrators of many different degrees,

the difficulty applying it to Construction curricula lies with the number of

disciplines which are gathered together under the Construction umbrella. This

makes the matching of courses to categories difficult and arbitrary, and leads

to inevitable disagreements in the assessment process.

While

it is true that the accreditation process used by ACCE goes beyond this

quantitative approach in its evaluation of the quality of courses and

qualifications of instructors, "credit counting" remains a

less-than-precise way of assessing whether true balance is being achieved by a

particular program. This is not to imply that this shortcoming has flawed the

accreditation process of those programs currently accredited by ACCE. It is,

however, entirely possible that both current and future candidates for

accreditation may be handicapped in their attempts to respond to the existing

criteria.

Much

of the debate regarding categorization of courses has revolved around

distinctions between construction science, business and management, and

construction. Often the category a course is placed in is determined by who

teaches the course, or more precisely, under which department it is offered. At

its 1990 annual meeting, ACCE added Item (f) to topics under the

"Construction" category, broadening it to include "applications

of business fundamentals, such as

construction

law, construction accounting, etc." A statement was also added to the

"Business and Management" section noting that "applications of

these (business) fundamentals to construction should be included in category 5

(f)".

While

fundamental courses are desirable, business and management courses tailored to

the needs of future constructors are an invaluable addition to the curriculum.

The real question to be considered is whether the course is being taught from a

technician or a manager's viewpoint. A construction accounting course taught by

a bookkeeper for a construction company will probably result in the course

receiving a "technician's" slant; the same course taught by a CPA or

CFO for a construction company will lean heavily toward managerial accounting.

The University of Washington has labored for many years to bring certain

business and management courses into the Building Construction program in order

to supplement the business school's "generic approach" with

industry-specific information. Competent professionals have been recruited to

teach these courses, thus providing insights into the business side of

construction which the program's graduates would not otherwise have.

Several

different methods of curriculum review have emerged from the different

disciplines related to Construction. The methodology established by the National

Architectural Accrediting Board (NAAB) was chosen as a model for the development

of this alternative approach to analyzing and improving the Construction

curriculum at the University of Washington. It utilizes

"achievement-oriented performance criteria" for the evaluation of

program content and student performance, assessing knowledge and skill

acquisition in terms of awareness, understanding, and ability (which has been

modified in our system tocapability ). The mechanics of this process are

described below.

METHODOLOGY

The

methodology we are following in the development of our alternative approach to

curriculum review is detailed below:

The resulting matrix is found in the appendix entitled "Proposed Competency Areas for Program Guidelines."

[Note:

We are currently at this step in the process.]

|

COMPETENCY STATEMENTS

The

critical element in the process described above is the development of competency

statements. These need to be both specific and assessable to serve as an

evaluative tool. Properly written, they will reflect the value which the faculty

places in the item, along with its relative weight within the overall

curriculum. Competency statements must also be realistic in terms of what can be

accomplished within the constraints of the program.

The

three levels of competency are further defined below:

|

1)

Capability - At this level, a graduate should be able to function

with little or no assistance, and with only general supervision. 2)

Understanding - At this level, a graduate should understand how

something is done, and be able to accomplish it with some assistance and

under direct supervision. 3)

Awareness - At this level, a graduate has been exposed to the

concept or skill, but does not possess sufficient knowledge or

understanding to function without additional instruction or experience. |

To

be of greatest use and to aid in their development, competency statements should

be grouped by curricular category, such as the example for scheduling below.

COMPETENCY STATEMENTS: SCHEDULING

In

the Administration Category, a BCon graduate should: - Be capable of reading and

analyzing schedules.

| -

Understand the use of schedules to manage day-to-day operations of a

company and its projects.

-

Understand the use of schedules to plan future work activities. -

Understand different types/hierarchies of schedules. -

Understand how schedules are implemented by project managers and

superintendents. -

Understand how and when schedules need to be updated. -

Understand the use of schedules in preparing claims. |

In

the Technology Category, a BCon graduate should:

|

- Be capable of analyzing a residential or light commercial project and determining its sequence of construction activities. -

Be capable of creating a bar chart for a residential or light commercial

project. -

Be capable of producing a precedence diagram for a residential or light

commercial project. - Be capable of producing an activity-on-arrow diagram for a residential or light commercial project. -

Understand how a short-interval schedule is created and used. -

Understand how to construct an "as-built" and

"but-for" schedule and what they are used for. -

Understand how to assign and level resources for a given schedule. -

Understand how to construct a cash flow schedule and "S"-curve. |

In

the Design Category, a BCon graduate should:

| -

Understand the relationship between design and construction function

relative to a project schedule.

-

Be aware of the constraints imposed on a project schedule by the design

and approval/permit process |

CONCLUSION

We

have established the structure and organization for our new model, and have

begun formulating competency statements. This task will be time-consuming,

especially in light of the number of areas of competency we have established.

This

process has been very worthwhile in itself, irrespective of results.

It is not presented as a prescription, but as something which seems to be

working for us, fitting both our psychological make-up and our vision for this

program. This paper should be viewed as input to other programs and the

accreditation standards. We encourage each of you to forward comments,

criticisms and additions. We have already received a draft from Cal Poly SLO of

curriculum elements including several competency areas which could easily be

added to our matrix. And, at the 1991 ACCE midyear board meeting, President

Roger Liska presented his thoughts on competency-based standards--including

forty-six examples of objectives--to accredited program directors.

In

the end, the efficacy of our model will be validated by the applicability of the

competency statements, measured both internally and externally.

REFERENCES

1.

American Council for Construction Education, Annual Reports 1989. 1990, Monroe,

Louisiana.

2.

ACCE, Standards and Criteria for Baccalaureate Programs (Form 103), 1990.

3.

Associated Schools of Construction, Annual Report and Minutes of the

Twenty-Sixth General Meeting, Peoria, Illinois, 1990.

4.

Liska, Roger, Competency-Based Curriculum Standards: Does ACCE Want to Move in

This Direction?, ACCE midyear board meeting, February 1991.

5.

Morrill, Paul and Spees, Emil R., The Academic Profession: Teaching in Higher

Education, New York, 1982.

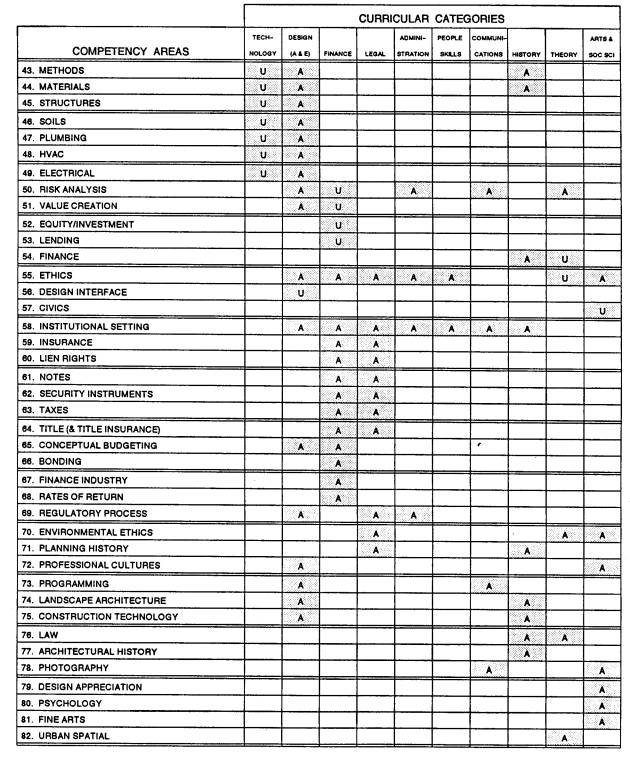

UNIVERSITY

OF WASHINGTON - DEPARTMENT OF BUILDING CONSTRUCTION PROPOSED COMPETENCY AREAS

FOR PROGRAM GRADUATES

(VERSION

3 UPDATED FROM DISCUSSION ON 12/26/90)

C-CAPABILITY, U=UNDERSTANDING, A-AWARENESS

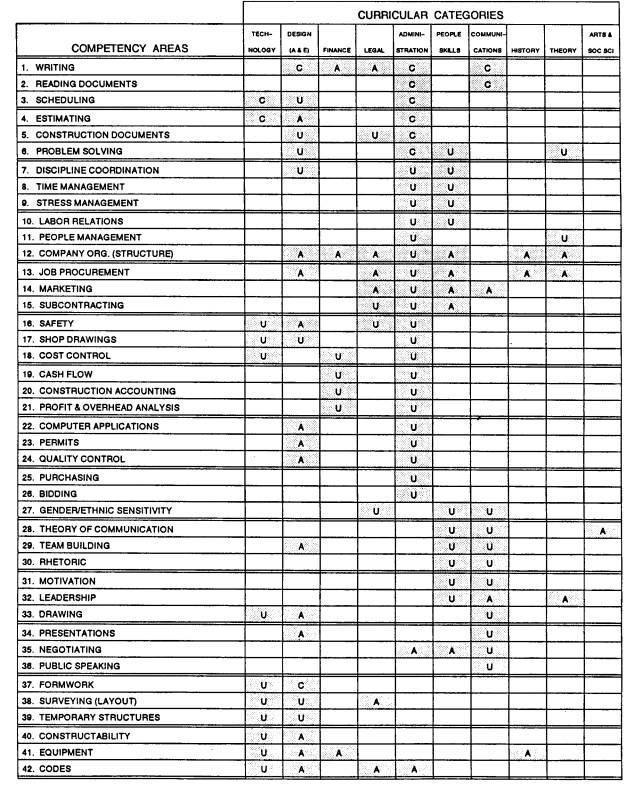

UNIVERSITY

OF WASHINGTON - DEPARTMENT OF BUILDING CONSTRUCTION PROPOSED COMPETENCY AREAS

FOR PROGRAM GRADUATES - PAGE 2

(VERSION

3 UPDATED FROM DISCUSSION ON 12/26/90)

C=CAPABILITY, U=UNDERSTANDING, A-AWARENESS