(pressing HOME will start a new search)

- ASC Proceedings of the 26th Annual Conference

- Clemson University Clemson, South Carolina

- April 8,9,10l 1990 pp 67-72

|

(pressing HOME will start a new search)

|

|

WHY

TEACH HISTORY?

|

George R. Rolfe University

of Washington Seattle,

Washington |

| While

not common among Construction curricula, the University of Washington

has successfully taught an undergraduate course in the history of

building construction for the past 20 years. The benefits from such a

course lie in preparing graduates to anticipate changes in the political

and business climates within which construction firms they will manage

operate, and in developing research and writing skills vital to

their career development. This history course is

currently organized in two related formats. The first presents a

chronological survey of societies that have influenced the construction

industry in the United Sates as we know it today. The second isolates

various aspects of the industry and examines the development of each one

across several different societies and time periods. The focus is on

understanding how and when present construction materials, equipment,

and organizational features came into being. Such a course can be

successfully taught with resources readily available within most

construction programs. |

INTRODUCTION

History

is not a subject found among Construction curricula at very many universities.

If you were to ask most students, history would not be among those courses they

would most like to take. Yet, in the fast-changing business and political

environments of today, some historical sense of the present shape and form of

the construction industry, as we know it in the United States today, is

important. Without a sense of history, we run the risk of training graduates to

be competent only as technicians in an industry that will need competent

managers.

For

nearly twenty years, the University of Washington has included one required

History of Building Construction course in its curriculum. This paper outlines

the case for including some survey of history in the Construction curriculum and

traces the development of the History course at Washington. Experience in

teaching this course has led to some insights into teaching methods that are

appropriate to Construction curricula, as well as some thoughts on useful

qualifications for course instructors.

The

author recognizes that not all Construction programs are focused the same as at

the University of Washington. Some programs may concentrate on heavy

construction where our focus is on building construction. Still others may be

focused on the engineering and construction techniques essential to the project

manager, while ours attempts to balance those skills with business skills

required to manage a construction company.

However,

it is the premise of this paper that, regardless of a program's focus, a course

in the history of the construction industry is important to include within the

curriculum

WHY

TEACH THE HISTORY OF CONSTRUCTION?

In

the face of faculty indifference, or even outright opposition, to including

history in the construction curriculum, what makes the experience at the

University of Washington worth presenting? A short and easy answer lies in the

number of students who indicate some version of "I hated the idea of

history, but it was a good course and I am glad I had to take it." For the

teacher, there are few greater rewards. However, there are other, more

academically based, reasons for including history in the curriculum.

A

case for including history within the curriculum

There

are two main branches to the argument for including history within the

undergraduate construction curriculum. Each is rooted in our mission of

preparing graduates to become effective in the construction industry. This is

not to dismiss or ignore valid arguments for broadening undergraduate liberal

arts education in general, which the author accepts and supports. Rather it is

to focus this paper more narrowly on the field of construction education.

The need to broaden understanding of the industry

If

we are educating graduates to eventually assume management responsibility for

construction companies, it is important for them to understand the forces that

impact the industry. For instance, the rather dramatic shift away from

"hard money" public bids toward "cost plus" negotiation as a

means for procuring construction services has caught some construction fines

without skills to effectively compete. The possibility exists that increased

public works spending in the near future may swing momentum back to bid jobs.

Yet these changes have strong historical antecedents.

Starting

in the 1830s with the rise of private, speculative, commercial builders in the

United States, it was common for construction work to be negotiated. Moreover,

construction work was often negotiated at a point in the process when

architect's and engineer's design work was not complete. It is, at least, likely

during a period of time when similar forces have dominated our industry, i.e.

strong private, speculative, commercial developer/clients, that similar

responses from contractors would be demanded. Yet those managers with only a

sense of the immediate past might assume that bidding is the only way of the

future and, consequently, fail to adjust their companies to respond to the new

realities of the business environment.

There

is no guarantee that, just because a manager of a construction company had taken

an undergraduate history course, he or she would necessarily have been able to

foresee these changes in how construction services are procured. However, if

such an undergraduate history course had been a part of their education and,

equally important, had that course focused on this type of historical sequence,

such a manager would, at the very least, be in a better position to anticipate

changes in a timely manner.

To

draw a second example, the current growth in "open shop" versus

"union shop" construction is probably partly a return to the

historical model for organizing labor on the construction site. Here there seem

to be two strong themes throughout history that are coming together today.

One

is the almost unbroken tendency towards specialization of labor over the past

3,000 to 5,000 years. Starting with the early specialization of miners in

northern Mesopotamia around 8000 BC, through the professional construction

managers of the Egyptians, to the common use of engineers by the Romans, there

were increasingly specialized crafts and labor on the construction site. With

the advent of freemasons for the building of Gothic cathedrals, craft

specialization took on a political and economic dimension. The culmination of

this labor specialization might be considered the modern craft or trade union,

the A.F. of L.

However,

the second historical theme is the organizational framework within which

material and labor have been managed on the construction site. For a variety of

economic and political reasons, the overwhelming tendency has been toward

strong, centralized management control In fact, until the 1930s in the United

States, the tendency was to have all crafts and trades working as employees of

one general contracting company resulting in high, fixed overhead for labor and

equipment.

During

the world depression, a lack of steady clients resulted in massive layoffs of

skilled tradesmen. These skilled tradesmen, in turn, realized that they could

subcontract their services on a more flexible and lower overhead basis and

compete for what little work was available. However, not until after World War

II, when low cost and fast reproduction of contract drawings became available,

was it possible for independent subcontractors to emerge as we them know today.

The

disadvantage of the independent subcontractor form of labor organization is the

difficulty in job site management control. For all of our efficiency and

productivity gains over the past 50 years, we still cannot complete major

construction projects in a time frame that matches those of the early 1900s. In

an era of high real costs of capital, time is money. It is quite possible that

the value of future contractor's services to the developer/client may lie at

least as much in the management of time as in managing actual construction

techniques.

It

is interesting to speculate on what the future development of the "open

shop" movement might be. Whether it turns out to be only an attempt to

control costs, or whether it focuses on the broader, and more historical, issues

of job site management control on the job site is unclear. However, it is

important to recognize that the particular form of construction management

typical of the industry in the United States is quite unique, both

internationally and historically.

Therefore,

it is valuable to place modern construction within the context of historical

events familiar to most educated persons. It is equally important to understand

the time frame within which the industry, as we know it today, has emerged. A

construction history course can give students such an awareness.

The

need to broaden and sharpen student skills

A

second set of arguments in favor of a history course lies in a recognition of

the skills required of competent managers of construction activities and

companies. Perhaps chief among these non-technical skills is the ability to

write well. More and more communication within the industry is written. More and

more contractual liability and financial issues are being resolved on the basis

of written documentation in both bid and negotiated work.

In

addition, research skills that are part of a good history course are extremely

valuable to have in managing construction. The ability to find and read

technical information, to organize that information for a specific purpose, and

to draw valid conclusions from that research are part and parcel of a

well-presented construction claim. To be able to present those conclusions in

well-written and persuasive arguments is a major part of the process. A

requirement for a written research paper has proven to be an effective way to

build skills in writing and research methods, and at the same time incorporate

them within broader curricular objectives.

It

is easy to overlook the value of this second set of arguments for including

history within the curriculum. Indeed, there are other ways in which to focus

attention on writing and research skills. Yet, the sad fact remains, we are

graduating people to go into the construction industry who sometimes cannot use

correct grammar, syntax, or punctuation, and whose ability to communicate

effectively will, most surely, hold them back from career advancement into

management ranks.

Summary

of case for including history in the curriculum

The

hypothesis of this paper is that some sense of history is an important part of

the educational experience of those attempting to become managers of

construction companies. The focus of that history should be on the forces that

have shaped the industry as we know it in the United States today, i.e.

primarily Western society and technology. The inclusion of one such course

within the average curriculum should be sufficient to give students a broad

sense of the evolutionary process and time frame within which our industry has

come into being.

The

inclusion of one such course within the curriculum also provides nearly ideal

conditions for focusing writing and research skills essential to an effective

manager. Based on experience at the University of Washington, many technically

competent students who show only marginal writing skills prior to taking history

turn out to be good writers. Moreover, this improvement in writing and research

skills seems to carry over into subsequent course work. It may be no more than

the emphasis on these skills required in a history course that results in

students focusing attention on improving their writing skills.

OUTLINE

OF HISTORY COURSE CONTENT

BCON

350 is the current course taught at the University of Washington. It has evolved

over the past twenty years with

a series of shifts in emphasis. Its early days emphasized the evolution of

materials used in modern construction. Gradually the addition of construction

equipment and methods such as fasteners, forming, transportation, and lifting

devices where included in the course. By the late 1970s the course had been

developed to a relatively stable point, reflecting stability within the

curriculum and in terms of faculty assigned to teach the course.

The

next stage of course development came during the early 1980s when a series of

different faculty members were assigned to teach the course. There were attempts

to include the study of architectural style, political and economic events, and

the development of cultural/national distinctions within Western history. As a

result, the course began to lose its focus on the history of construction.

In

1984 two new text books were introduced that served to refocus the course. One

is Henry Cowan's The Master Builders covering

Western history from Mesopotamia to the Industrial Revolution, ending in 19th

Century Europe. The second text is Carl Condit's American Building covering building and construction in the United

States from 1600 to the present. These texts are still in use, although there is

a serious need for a new text to cover the United States experience.

Current

focus of the course

Currently

the course has a dual format that incorporates much of what has been included in

the past, but focuses on factors which have influenced construction. One format

presents information in a rough chronological time frame, by discrete societies

and/or cultures, throughout the period from 8000 BC to the present. During this

first part, the course traces the evolution of those Western cultures which have

led to the dominant features of United States construction technology and

organization.

A

second format isolates important features of current construction materials,

equipment, and organization, and traces their evolution over time. Here the

focus is on the evolution of discrete elements such as concrete, or lifting

devices, or organization of capital/labor rather than on discrete societies.

This seems to work best after an overall frame of reference has been established

during the early part of the course. The author has unsuccessfully tried

reversing the order of presentation.

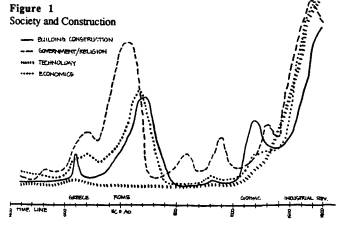

Chronological presentation of information

The

first part of the course looks at a series of discrete societies and cultures

from the standpoint of how geography/topography/climate, government/religion,

economics, and technology have affected construction. There are clear

distinctions between societies wherein one will excel in the area of government

as evidenced by a strong military presence, such as the societies of

Mesopotamia, which is used to overcome shortcomings in natural settings, or

economics. Another society, such as Egypt, existing at the same time, may be

able to use accidents of natural settings which provide security from external

attack to focus efforts on advancing technology. At other times a society may

emerge which combines significant advances in several areas at one point in

time, such as Rome, resulting in a seeming burst of progress in construction as

well as many other aspects of society. (See Figure 1)

During

this part of the course it is important to try to knit together all aspects of a

given society in order to understand impacts on construction. There are clear

differences between cultures that invent significant new technologies and those

who borrow technology and use it to significantly improve standards of living.

For instance, even though Rome created the highest standard of living in all of

Europe, at least up until the 17th Century, there were relatively few

technological innovations throughout Europe during the 500 years of Roman rule.

Roman society borrowed organizational methods, technology, and even culture from

other less advanced or older societies.

For

each society studied the focus is on how it adapted and organized resources to

deal with construction. For example, not much time is spent on the evolution of

the wheel until its introduction into construction, by the Greeks, in the form

of crude carts to transport finished stone from the quarry to the construction

site. Shortly after this time, crude capstans employed wheels to lift light

construction materials into place. But it was not until Archimedes developed the

dolphin for military uses that wheels were incorporated into lifting devises

flexible enough to lift heavy loads vertically and swing them horizontally, as

used by the Romans in their construction efforts.

Likewise,

the use of metals for implements of warfare in Mesopotamia or for jewelry in

Egypt is of less interest, even though it predates the use of metal in

construction by at least 1,500 years. Probably the first significant use of

metal appears in Greece as fasteners (nee cramps) used for aligning individual

stones in columns or as simple false work under the architrave e.g. lintel, of

Greek Temples. This early use tends to disappear in Roman construction because

of the introduction of concrete as a binder.

Therefore,

even though the Romans borrowed the classical orders and overall building forms

from the Greeks, they used an accident of nature, i.e. concrete made from

natural pozzolana cement, to radically change the method of constructing their

buildings. After this time metals are limited to lead used in roofs and

plumbing, and iron hardware until the Industrial Revolution.

Time

and time again, combinations of political stability and economic activity can be

seen to produce societies with high standards of living. But it is not until the

Industrial Revolution that we see these relatively high standards of living

combined with significant innovation in technology affecting construction during

the 17th and 18th Century. It was the combination of stable government, strong

economy, and the application of theory, first "invented" by the

Greeks, that allowed England to advance construction so rapidly. Even in the

face of this rapid improvement in construction methods and techniques, there was

more absolute innovation going on in France and, later in Germany, even though

neither was as politically stable nor economically strong as England.

This

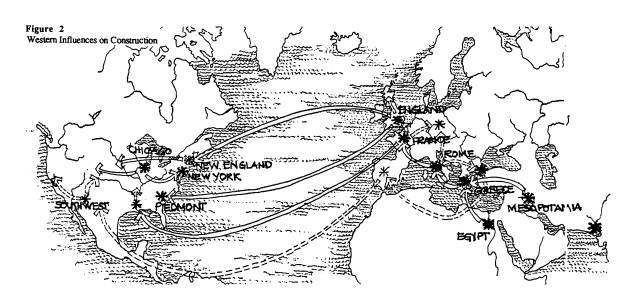

chronological format outlines societies starting in areas to the north of the

Persian Gulf, moving west and north to England before jumping to the United

States.(See Figure 2) This sweep covers the period from approximately 3500 BC

until today and includes the following societies:

|

|

| Figure

1 Society

and Construction |

|

| Figure

2. Western

Influences on Construction |

Each

of these examples from history can potentially shed light on possible responses

from societies with similar characteristics today. In addition, this part of the

course sets the general time frame within which specific aspects of construction

have emerged.

Specific

materials. equipment, and organization

The

second part of the course outlines the development of specific aspects of the

construction industry as we know it today. Here the emphasis is on showing the

impact of various dimensions of society on the evolution of a single aspect of

construction, and how ideas and technology may have been borrowed from other

societies and times to combine in new methods, materials, or technology.

For

instance, the development and use of metals in construction has been relatively

lengthy and continuous, starting with the first uses of malleable iron or copper

cramps as fasteners in Greek buildings. Without experiments in forging and

annealing metals for use in weapons, the technology for making cramps might not

have been available. Roman advances in glass blowing developed the ability to

raise temperatures high enough to actually melt metals, making casting possible,

although not yet economically feasible.

It

was not until the development of the blast furnace in the 16th century, coupled

with the use of charcoal, that casting became feasible for construction uses.

This resulted in the rapid depletion of European forests, which led to the use

of coal in making metals. Demand for fireproof mill construction during the

Industrial Revolution focused attention on the development of metals for large

scale construction use. With the development of the Bessemer process in the

United States, and the substitution of coke for coal, modern metal usage came

into widespread use in the late 19th century.

Engineering

theory paralleled advances in metal technology, and was relatively well advanced

as early as the 15th century. Technology, theory, and economics developed at

similar paces after that time. Contrast this with the development of concrete as

a construction material. With the exception of Rome, no society was able to

develop and use concrete on a wide scale until the beginning of the 19th

century.

Advances in chemical theory were essential before a consistent supply of cement for concrete could be made available. This did not occur until less than two hundred years ago. Even then concrete was not incorporated into building structure until the development of mathematical tools to solve indeterminate equations about one hundred years ago. Consequently the use of concrete has fewer historical antecedents, partly leading to the more imaginative and unrestrained uses of the material n construction today.

In

an entirely different area, the organization of construction activities, as we

know them today, has many parallel it Fluences throughout history. Who is the

client, who controls material and labor supplies, when did money become the

medium f( r procuring construction services, and how that changed he client/

contractor relationship are all important precedents fort to organization of

modern construction activities.

The

fact that centralized political and economic control of society has almost always led to massive public

works construction as opposed to business- and consumer-oriented construction is

clearly evident throughout history. The presence of a politically independent

and economically strong middle class has been the basis for business and

consumer based construction activities. Historically, oligarchies and other

economically elite groups have tended to be clients for large scale, lavish

private constriction at the expense of public works, not unlike the very recent

past in the United States.

This

portion of the course knits together the evolution c construction materials,

equipment, and organization to how various aspects of society have influenced

the construction industry we know today. Just as there is constant interplay

between the yin and yang in Eastern thought, societies a re constantly demanding

new building forms at the same tine that adapting economies of scale and

organizational responses to meet these needs. Sometimes supply precedes demand

and at others, the reverse is true. But neither can be out of balance for long

periods of time.

At

various times over the past four years, the course has looked at the following

aspects of the construction industry and traced their evolution throughout

history:

|

Not

all subjects have been covered each quarter the course has been taught.

Variables that influence how far we get in the class include the amount of

student interest and discussion during the first part of the class and the speed

with which each class picks up the flow of historical ideas. From our

experience, there are relatively wide variations from class to class.

APPROACH

TO TEACHING METHODS

This

particular course has always served the construction student. Therefore, the

emphasis in setting up teaching methods has been on finding ways to bring into

sharp focus the events and forces shaping the construction industry in the

Untied States today.

Class Presentations

The

primary teaching format is a lecture and question/answer class session. The

course is taught over a ten-week quarter, currently with the class meeting three

times per week for 50 minute sessions. The author has also taught two 80-minute

sessions per week and found that 80 minutes is simply too long to maintain

student attention for a lecture course like history.

Part

of what varies from class to class is the interest level of the students in

asking and discussing questions. Often there is an attempt to relate the topic

for each session to some current event that should be readily apparent to

students. Sometimes this sparks questions and a lively discussion, which

inevitably slows down the speed with which the "history" material can

be presented. However, the increased interest level of class sessions together

with the added relevance and ultimate value of the course is well worth the

variable pace.

Most

sessions are illustrated by anywhere from 10 to 60 slides. These slides are used

to illustrate points made in the lectures, rather than to serve as the subject

of the lecture itself. In this sense, the use of slides is quite different from

that typical in an architectural or art history course. The purpose of

construction history is not to dwell on the merits or flaws of any one object or

period, but to survey and compare the development of ideas, technology, and

methods. It seems to work well to compare and contrast two or more examples as

illustrations rather than to spend a great deal of time analyzing one example.

The

slides are drawn from the extensive College collection, from a rather large

personal collection of the current Dean (who previously taught the course), and

the author's own personal collection. In our case we are fortunate to be

administratively housed in a College of Architecture and Urban Planning with a

slide collection approaching 100,000 individual slides. Even so, we are

constantly requesting slide copying to augment the roughly 3,000 slides in the

construction collection, which the slide librarian has been more than willing to

do.

One

cautionary note about what class presentations are not. There is no attempt to teach the course using extensive events

and/or dates. Students are responsible for knowing seminal events in a rough

time frame, at least to the correct century. Contemporary thought regarding the

teaching of history is moving away from the idea of history as a series of

discrete events related in time. The history of construction is particularly

inappropriate to attempt to attach dates to events, partly because

the

events themselves as so indistinct, and partly because there has been so little

historical research that even clearly defined events are difficult to accurately

date.

Student Responsibilities

One

important responsibility of students is to come to class prepared to

participate. In fact 5% of the course grade is earned through class

participation, although attendance is not taken. There are usually 40 to 50

students per class, which is clearly beyond the size for operating in seminar

fashion. However, you can engage that many students in lively discussion over

the course of a ten-week quarter.

There

are two quizzes and one final that are worth a combined 4550% of the course

grade. These exams are split two thirds objective answer, i.e. true/false,

multiple choice, or matching questions, and one third essay answers. Part of the

grade on the essay portion is based on technical writing skills, but not on

style. Sample exams are on reserve in the library so that all students are on an

equal footing.

The

largest part of the course grade is dependent on an individual research paper.

Students are free to choose any topic they wish, although they must have their

topic and bibliography approved. This ensures appropriate and adequate source

materials are available for good research. Students are responsible for

identifying factors present within a society that influenced the important

features of their individual topic. They are also encouraged to draw parallels

or conclusions that have relevance for construction today, although this latter

is not a required part of their course grade.

Papers

routinely run between 10 and 20 pages including illustrations. Students must use

correct research writing skills such as annotations, footnotes, references, etc.

Evaluation of papers is based 30% on appropriateness of the topic, 30% on

research approach, 30% on completeness of the research, and 10% on technical

writing skills, including neatness. There are three intermediate review points

throughout the quarter with up to 9 bonus points (out of a total of 150 points)

earned for meeting these intermediate deadlines.

In

reviewing research papers, what is most surprising is the correlation between

the level of performance in more technical construction courses and history.

Very seldom will there be a case where someone does outstanding work in history

and relatively poorly in other courses. This tends to support the argument that

writing could probably be incorporated in most courses without significantly

altering the performance curve of students.

Thoughts

on qualifications for course instructors

None

of the instructors that have taught BCON 350 over the last 20 years has been

trained as an historian. This is not to indicate that an interest in and love of

history is not probably essential in order to do a good job. Instructors must be

comfortable with some form of lecture format, and have some level of familiarity

in using graphic aids.

The

author was very fortunate to have the course outlines, texts, and the 15 year's

experience of others who taught this history course to begin to build on. This

contribution cannot be overemphasized. However, none of this background came

from conventional "history" departments or faculty. In fact, one

impression from interaction with the members of a strong architectural history

faculty in our College is that formal training in history may be somewhat of

hindrance in teaching a broad survey course. This has primarily to do with the

definition of what is appropriate subject matter to an "historian" as

opposed to the necessarily broader view of the construction educator.

For

instance, this course uses Cowan's book The

Master builders as a required text, and it has proven to be

excellent. However, Cowan's subsequent book, Science

and Technology, intended to follow chronologically The

Master builders, is of no use to our course because it is much too detailed

in terms of dates, events, and people.

Consequently, it is very difficult to follow the thread of an idea without getting bogged down in what for a broad survey

course such as ours is minutia.

Therefore,

in searching for appropriate faculty to consider teaching a course in

construction history, it might be fruitful to look among your own construction

faculty colleagues for someone who:

|

Such

a person will need constant encouragement and support, particularly during the

early stages of developing the course.

The author would be excited about sharing resources, experience, and ideas with

anyone so interested.

SUMMARY

For

those programs which aim at educating managers of construction companies as well as of construction activities on the job site, a course in construction

history is valuable to include in your curriculum. There are recurring ideas and

events throughout history that are manitest in our society today, and which have

sometimes profound effects on the construction industry without most of

us ever being aware of them. A

properly conceived and effectively taught course in construction history can prepare students to recognize these influences in a time frame

that allows for effective management responses.

Over

the past 20 years such a course has been included in the curriculum at the

University of Washington. It is

currently a one quarter course that is broken into two parts. The first part

traces a series of discrete societies

that have had primary influences on the construction industry as we know it in

the United States today. The second part focuses on key aspects of

that industry and traces their evolution across these various societies.

The

resources for teaching such a course probably already exist within most

construction faculties. All that is needed is some administrative support, some

reference materials that are readily available, and some students. The rewards

have been very gratifying at the University of

Washington.

REFERENCES

|